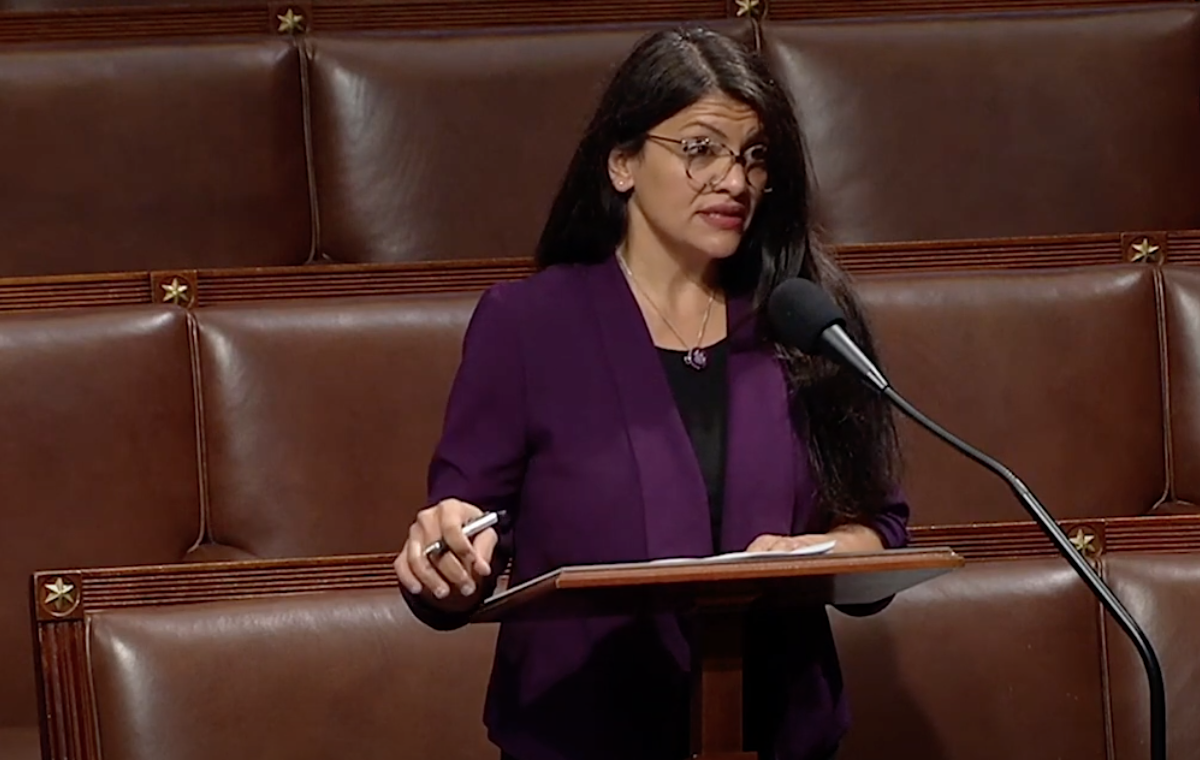

US Congresswoman Tlaib Reintroduces Amendment To Reform Espionage Act

The following article was produced for paid subscribers several days ago. It was unlocked on July 12 for the public. Become a monthly subscriber.

Michigan Democratic Representative Rashida Tlaib reintroduced an amendment to the Espionage Act that would curtail the United States Justice Department’s ability to abuse the draconian law.

Defending Rights and Dissent, a civil liberties organization that champions the right to freedom of political expression, again collaborated with Tlaib’s office on the development of the amendment.

“It is long past time for Congress to step up and end the increasing abuse of the Espionage Act,” declared Chip Gibbons, who is the policy director for Defending Rights and Dissent. “Rep. Tlaib’s amendment is the boldest, most comprehensive effort we’ve seen yet. It would truly limit the Espionage Act to the prosecution of spies, not journalists, not their sources, and restore basic principles of due process in the event the government did take someone to trial.”

Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg came out in support of the amendment. “For half a century, starting with my own prosecution, no whistleblower charged with violating the Espionage Act of 1917 has had, or could have, a fair trial. These long-overdue amendments would remedy that injustice, protect the First Amendment freedom of the press, and encourage vitally-needed truth-telling.”

There is definitely a strong case for repealing the Espionage Act in its entirety. But Tlaib’s amendment represents an opportunity to diminish the immense power that US prosecutors have to wield the World War I-era sedition law in support of military and national security agencies, which retaliate against dissenters.

Such an amendment would greatly benefit whistleblowers who follow in the footsteps of whistleblowers like Reality Winner, Terry Albury, Daniel Hale, or Edward Snowden—all unjustly punished with Espionage Act charges.

Prosecutors do not have to prove a whistleblower had an intent to harm to convict them. The mere fact that they signed a non-disclosure agreement and have knowledge that certain files or documents were classified is considered enough to convict a person of violating the Espionage Act.

To change this aspect of prosecutions, the proposed amendment adds a “specific intent to injure the United States or advantage any foreign nation.”

The amendment gives those accused of violating the Espionage Act a right to share “testimony of purpose” and put forward an “affirmative defense.”

“A defendant charged with an offense under section 793 or 798 [of the Espionage Act] shall be permitted to testify about the purpose for engaging in the prohibited conduct,” the amendment states.

Any defendant engaged in “prohibited conduct” would have the ability to make the case that their actions were justified because they intended to expose a violation of a law, rule, or regulation. Or they had evidence of a “gross mismanagement, a gross waste of funds, an abuse of authority, or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety.”

Incorporating an “affirmative defense”—and a right to testify about the purpose for disclosing information without authorization—would establish a public interest defense. For the first time since the Justice Department started applying the law against whistleblowers, a person could describe why they made disclosures and argue before a jury that their actions were justified.

Notably, a whistleblower would not lose the right to make an affirmative defense if they went to the press instead of making disclosures through internal channels of government.

Yet another section of the amendment outlines “covered persons” in order to clarify that the law should never be applied to journalists, publishers, or members of the news media.

The proposed amendment was attached to the National Defense Authorization Act, an annual bill that contains the budget for the US military.

When Tlaib previously introduced the amendment, she attempted to attach it to the Protecting Our Democracy Act, which the House passed in response to President Donald Trump’s abuses of pardon power and effort on January 6, 2021, to incite a riot that would block Congress from certifying the 2020 election that he lost.

The House Rules Committee blocked that version of the amendment after arbitrarily deeming it was “out-of-order.”

In 2020, Hawaii Democratic Representative Tulsi Gabbard introduced a similar amendment called the Brave Whistleblowers Act. It went nowhere.

Oregon Senator Ron Wyden and California Representative Ro Khanna introduced Espionage Act reform legislation months before Gabbard. It added protections for journalists, but their proposed amendment contained no public interest defense for whistleblowers.

While Tlaib deserves credit for once again introducing the amendment, her office seems uninterested in publicizing the effort. Tlaib’s office did not release a press statement nor did they in 2021 before the House Rules Committee blocked the amendment.

The United Kingdom authorized WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s extradition to the US for a trial under the Espionage Act, which would greatly impact press freedom, free speech, and due process rights.

Like her colleagues, Tlaib has maintained a disappointing level of apathy and silence leaving the void to be filled by senators and representatives who may lash out against Assange when they hear or see his name because they cannot control their venomous hatred. These elected officials do not care what damage is done by prosecutors. However, officials like Tlaib who understand the issues can speak out.

***

Congress needs public pressure if there is any chance that the House Rules Committee will allow the amendment to be seriously considered for passage. That is why Defending Rights and Dissent put together a tool to contact their representative to demand that they support this crucial amendment to protect whistleblowers and journalists.

If you're a US citizen or resident, take a brief moment to write to your member of Congress. (I did.)

Comments ()