Throughout The World, Very Few 'Legally Successful' Whistleblowers Are Made Whole

Government Accountability Project and International Bar Association examine the state of whistleblower protection laws in 37 countries

Whistleblower rights in the United States are "quite sophisticated" and often reflect "best practices" for protecting whistleblowers. However, as noted in a recently released study, rights in the U.S. often "fail such fundamental criteria as court access for government whistleblowers, as well as protection for those outside the workplace and against non-workplace retaliation."

The study [PDF] from the Government Accountability Project and the International Bar Association examines whistleblower laws in 37 countries. They particularly focus on the kind of "blind spots" that as a result, or feature, lead to a low success rate, when whistleblowers pursue claims.

To assess each country, the organizations considered whether a country had: "broad whistleblowing disclosure rights with 'no loopholes,'" rights that covered a "wide subject matter scope," the "right to refuse violating the law," protection against "spillover retaliation at the workplace," protection beyond the workplace, "reliable identity protection," protection from the "full scope of harassment," and whistleblower rights that were shielded from gag orders.

They also examined essential support services provided, whether a country allows third parties to resolve disputes, "realistic" time frames for acting on rights, "compensation with 'no loopholes,'" relief before a final determination in cases, accountability for those who repeatedly engage in whistleblower retaliation, coverage for legal fees and costs, the ability for a whistleblower to transfer to another office or worksite, "credible internal corrective action," and transparency and review of whistleblower laws.

Generally, the study found it difficult to uncover case decisions and statistics to determine how effective the laws are when whistleblowers come forward. But they were able to conclude that whistleblower laws are "widely underutilized" in most of the countries.

"The majority of whistleblowers do not formally succeed in retaliation complaints. In nations where cases are arising with some frequency (30 or more cases), slightly less than 13 percent of whistleblowers won formal final decisions," the report stated.

***

Some Highlights From The Study

Remarkably, the study found Canada's whistleblower law, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act, is "nearly entirely dormant."

"Only eight whistleblowers representing six controversies were allowed to bring [retaliation] claims before the tribunal [under the law] between 2005 and January 2020, when 358 complaints were submitted to the Integrity Commissioner’s Office," according to the report.

"Of the two cases ultimately determined on the merits" in Canada, "the whistleblower was unsuccessful in both, while each took an extended period of time. It takes tenacity and financial resources for any whistleblower to sustain a [retaliation] dispute for over six years only to lose."

Two laws in New Zealand—the Employment Relations Act and the Protected Disclosures Act—are supposed to protect whistleblowers, but in 11 cases that were found, eight whistleblowers lost on the merits. Whistleblowers were ordered to pay the "opposing party's costs in addition to their own" in four cases.

"‘Loser pays’ rules are particularly disadvantageous to those already unemployed and without income," the report declares. "Further, whistleblowers frequently are self-represented, trying to act on their rights through trial and error. Without the benefit of professional legal counsel, whistleblowers are more likely to be regarded as disruptive plaintiffs bringing meritless claims than [altruistic] citizens."

A law for whistleblowers was established in 2016 in Albania, and a provision that applies to the private sector went into force the following year. Yet the study was unable to find "any publicly reported case data under this law or reports on whistleblower disclosures."

"The law requires private entities with more than 100 employees and public entities with more than 80 employees to establish internal whistleblower reporting units, as well as procedures for protection against retaliation. Resistance from the private sector impacted the effectiveness of the new law during the initial phase of establishing internal reporting units."

The report adds, "Some businesses considered the process a 'state intervention in private affairs.' Others simply refused to establish the internal reporting units."

Only one whistleblower case was found under the Working Environment Act in Norway. In 2009, a whistleblower at a "non-destructive testing company in Oslo" allegedly "witnessed serious problems with welding and exposure to radioactive materials. The whistleblower made disclosures internally to the chief executive officer (CEO), but the CEO concealed and ignored the disclosure.”

"The whistleblower’s supervisor retaliated with acts such as spitting, throwing a security tape and threatening termination of employment," the report recounts. "The whistleblower was ultimately terminated. The whistleblower won the case in the lower court but did not receive any financial compensation. After appeal, the court awarded approximately $10,860."

A Public Interest Disclosure Act in the United Kingdom uses employment tribunals for litigating whistleblower cases. According to the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Whistleblowing in England and Wales, "more than three out of five whistleblowers" at tribunal hearings "have weaker representation power than the employer." Nearly half of whistleblowers in 2018 had to represent themselves.

Whistleblowers in the UK were likely to have their claim dismissed in early stages, and they were unlikely to succeed at their final hearing.

The APPG broadly criticizes the process because it is nearly impossible for a tribunal to "correct the wrongdoing itself," which is why whistleblowers risk their livelihoods and "speak out in the first place."

From Bosnia and Herzegovina to Zambia, most of the countries do not publish records on the outcomes of whistleblower cases under their laws.

Both the Government Accountability Project and the International Bar Association believe every country "should publish case decisions online within searchable databases." They should also produce regular reports on the effectiveness of whistleblower laws and their benefits to society.

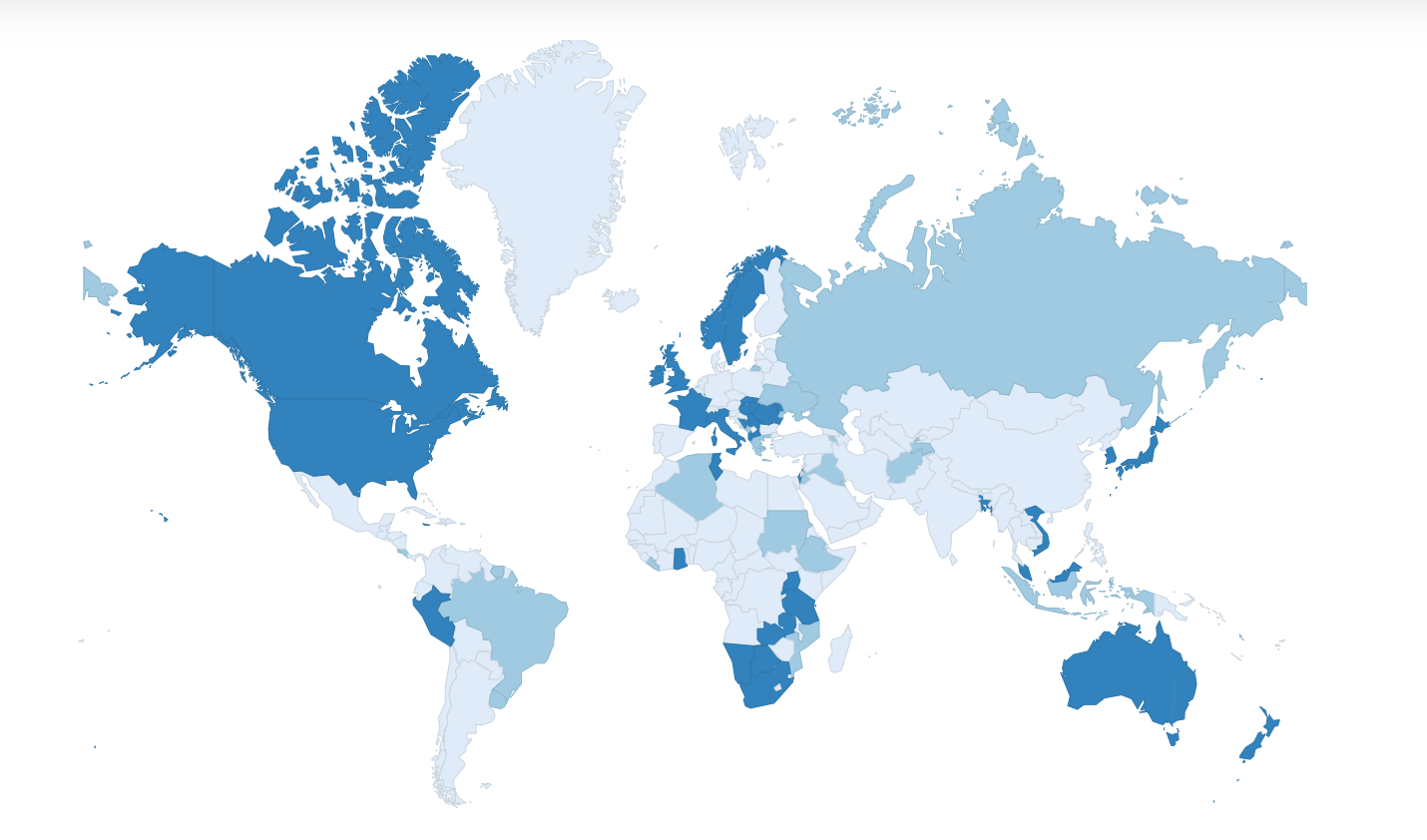

GAP plans to track the state of whistleblower laws worldwide through a map that follows legal developments and newly adopted reforms.

As both organizations acknowledge, their study is of limited value because so little public information was available. They were, however, able to show the many ways the "chilling effects of repression" impact accountability.

"Almost no legally successful whistleblowers receive enough relief to make them whole," the organizations concluded, and that affirms the need for substantive changes throughout the globe.

Comments ()