Freedom Of Information: US Government Secrecy As Bad As It Was Under Trump

When it comes to the Freedom of Information Act, government secrecy under President Biden is just as bad or slightly worse than it was under President Trump.

Support independent journalism on government secrecy, press freedom, and whistleblowing. Become a subscriber of The Dissenter.

The United States government responded to nearly two out of three Freedom of Information (FOIA) requests in fiscal year 2023 by censoring, withholding, or claiming that they could not find any records.

That means—when it comes to FOIA and the public's right to know—government secrecy under President Joe Biden is just as bad or slightly worse than it was during the last fiscal year of Donald Trump’s presidency.

A fiscal year for the U.S. government begins on October 1 and ends on September 30. Since fiscal year 2008, the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Information Policy has collected annual reports that show how agencies "comply" with FOIA.

For Sunshine Week (March 10-16), The Dissenter examined data from October 1, 2022, to September 30, 2023, which illustrates the persistent lack of openness in government.

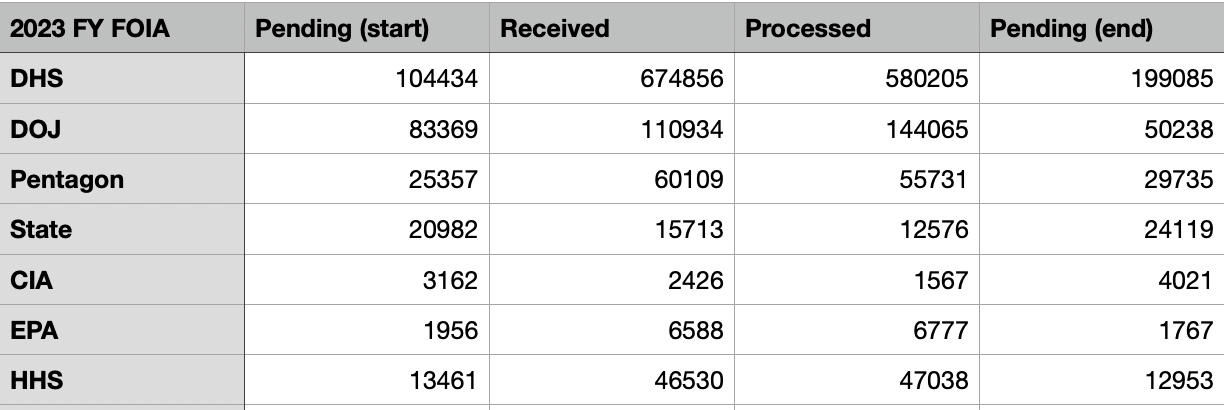

Agencies received more than 1.1 million FOIA requests—a new record for the U.S. government.

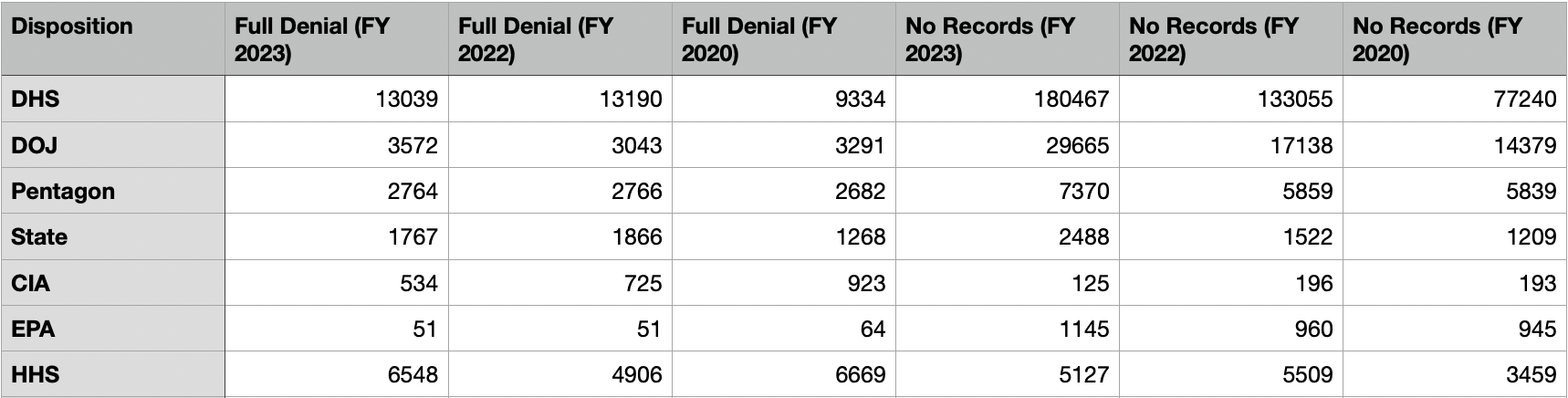

More than 20 percent of the time, agencies claimed that there were “no records” that were responsive to a request. That suggests that in numerous instances agencies did not perform adequate searches for files.

Nearly 40 percent of requests were “partially denied.” Compared to the period from October 1, 2019, to September 30, 2020, which was Trump’s last fiscal year in office, a similar amount of record requests were “partially denied.”

Three and a half percent of the time agencies claimed exemptions and fully denied the request, which is slightly lower than the last year of Trump’s presidency.

Only 16 percent of requests were fully granted, a decrease from 21 percent in fiscal year 2020.

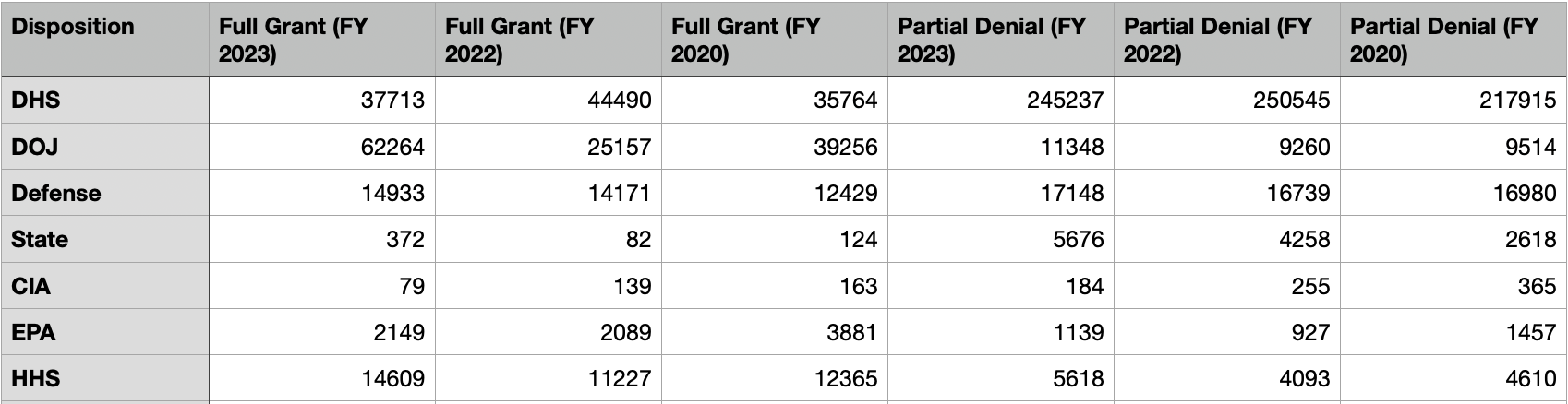

Specifically, since fiscal year 2020, the number of requests where the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) claimed that they could find no records has more than doubled.

The number of requests where the Department of Justice (DOJ) claimed that they could find no records has nearly doubled since fiscal year 2020.

The Pentagon, State Department, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Health and Human Services (HHS), which receive a high number of requests annually, increasingly claimed that they could not find any responsive records.

As noted by MuckRock, a nonprofit site that enables public records requests, “it typically takes 278 days for requesters to get a response” from any given U.S. government agency. “And that response isn’t always records—it’s often just a note saying ‘We received your request and will begin to search for the records you’ve requested.’”

Requests by journalists, media outlets, or advocacy organizations may be labeled “complex” requests, which means that they will take much longer than a request submitted by a private individual. It sometimes can take an absurd amount of time for agencies to fulfill a request.

One complex request for documents from the Pentagon was completed nearly 12 years later (4296 days). The State Department also took nearly 12 years to complete a complex request.

Nearly 9 years later (3189 days), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) completed a complex request. The DOJ took a little more than 7 years (2639 days) to complete a complex request.

Furthermore, a “disturbing trend” that the Associated Press highlighted during Trump’s presidency has continued: when a requester challenged an agency’s decision to improperly conceal records, one-in-three cases resulted in a partial or total reversal.

But there were more than a million FOIA requests in the last fiscal year, and only 14,789 appeals. A minuscule number of people, organizations, or businesses had the wherewithal or resources to ensure that they obtained the files, which they were seeking.

At the DOJ’s annual Sunshine Week event, Acting Associate Attorney General Benjamin Mizer once again emphasized that Attorney General Merrick Garland adopted new FOIA guidelines in 2022. The heads of all executive branch departments and agencies are supposed to “apply a presumption of openness.”

“In case of doubt,” the guidelines instruct, “openness should prevail.”

However, for fifteen years, the DOJ has promoted similar pledges. In 2009, Attorney General Eric Holder claimed the government would only defend a denial of a FOIA request in court if the agency reasonably foresaw that “disclosure would harm an interest protected by one of the statutory exemptions” or if disclosure was “prohibited by law.”

Officials under President Barack Obama continued to fight the release of secret legal opinions and flouted this guideline.

Mizer boasted, “We received more than 110,000 requests—a record—and processed over 144,000 requests—another record. In so doing, we were able to achieve a 32 [percent] reduction in our backlog.”

What Mizer neglected to say is that the DOJ responded to 23 percent of requests by fully denying the request or claiming that the department had no records. That undoubtedly helped the DOJ substantially reduce the department’s backlog of requests.

The truth is that U.S. government agencies are overwhelmed by the surge in FOIA requests. Many agencies had more pending FOIA requests at the end of fiscal year 2023. Rather than push for more funds to improve the process, agency officials tolerate the dysfunction (perhaps, because it benefits administrators).

In 2022, the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) called attention to this systemic problem. “An uptick in submitted FOIA requests, combined with the chronic underfunding of agency FOIA offices, means that agency backlogs and processing delays continue to increase."

"When agencies do respond to requests, FOIA exemptions meant to protect classified or otherwise legally sensitive information are often used to excessively withhold information that rightfully belongs to the public," POGO added.

POGO recommended that Congress add a “public interest balancing test” to FOIA when it comes to records that agencies claim may cause potential harm. They also urged lawmakers to require proactive disclosure of documents by agencies and create “line-item budgets” so that agencies have the necessary funds for processing FOIA requests.

Those are fixes that could bring more sunshine to government, however, whether agencies are collectively willing to improve the ability of journalists, media outlets, advocacy organizations, and citizens to hold them accountable is debatable.

Some of the data compiled for this article:

Comments ()