Twenty Years In A Security State: Guantanamo Whistleblowers Who Spoke Up Against A Legal Black Hole

[Editor's Note: To mark the 20th anniversary of the rise of the American security state after the September 11th attacks, The Dissenter continues a retrospective on this transformation in policing and government.]

President George W. Bush and his administration were offended in 2006 when Amnesty International called the Guantánamo Bay military prison the “gulag of our time.”

“It's an absurd allegation. The United States is a country that promotes freedom around the world. When there's accusations made about certain actions by our people, they're fully investigated in a transparent way. It's just an absurd allegation,” Bush remarked.

Senator Mitch McConnell, who was the majority whip for Republicans, said, “the gulag comment” was “utterly outrageous. There is no country in the world that has stood for human rights more than the United States. We've been an example to the rest of the world.”

The first detainees arrived at Guantánamo on January 11, 2002. Military personnel and intelligence agents transported 780 people to the prison.

As the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) detailed [PDF] in 2007, both present and former prisoners consistently alleged that they had “suffered systematic abuse at the hands of U.S. military personnel.”

The U.S. military also “openly acknowledged that many of the men at Guantánamo [did] not belong there.”

Only a few stationed at Guantánamo dissented in the immediate years after hundreds were brought to the detention camps.

Still, their testimony against the torture, abuse, and indefinite detention of prisoners captured in the “war on terrorism" helped defense attorneys and human rights groups challenge the legal black hole established by the Bush administration.

'Snatch Squads' And Sexual Abuse Against Prisoners

Eric Saar was a military intelligence linguist at Guantánamo from December 2002 to June 2003 and witnessed engaging in religious and sexual abuse against prisoners.

He wrote a memoir, Inside the Wire, and was considered one of the first high-profile whistleblowers to emerge from the military prison.

In 2005, he told The Observer, a British Sunday newspaper, “Prisoners were physically assaulted by 'snatch squads' and subjected to sexual interrogation techniques.”

“Some female interrogators stripped down to their underwear and rubbed themselves against their prisoners. Pornographic magazines and videos were also used as rewards for confessing.”

Saar further alleged that he witnessed a female interrogator take off some of her clothes and smear fake blood on a prisoner. That prisoner was then told it was menstrual blood.

He saw the impact of indefinite detention, where detainees attempted suicides and suffered from serious mental illnesses. “One detainee slashed his wrists with razors and wrote in blood on a wall: 'I committed suicide because of the brutality of my oppressors.’”

The “snatch squads” Saar observed were known as the Initial Reaction Force (IRF). They were deployed to deal with “uncooperative prisoners.”

An IRF team once broke a prisoner’s arm while he was at Guantánamo. In fact, the IRF was so brutal that during a training session a U.S. soldier posing as a “detainee” suffered brain damage.

To conceal the violence from senior officials that visited Guantánamo, staff would fake interrogations. “Prisoners who had already been interrogated were sat down behind one-way mirrors and asked old questions while the visiting officials watched.”

“Some of the most severe physical abuse reported at Guantánamo,” according to CCR, was “attributed to the IRF.” They carried Plexiglas shields and deployed tear gas and pepper spray. Violence by military guards occurred regularly enough for prisoners to develop a term for it: “being IRF’d.”

During a book event on May 5, 2005, Saar stated, “Guantánamo Bay, to me, represents a failed strategy in the war.

"I actually believe [it] could be producing more terrorists in the long run, especially as we have this attempt to win hearts and minds of the Arab people, and we defy the very values that we’re trying to promote around the world.”

Fear Of (Whistleblowing) Muslims At Guantánamo

As a Muslim military chaplain, James Yee challenged torture and abuse at Guantánamo while standing up for prisoners’ rights to practice their religion. He also helped the prison develop a policy that would ensure the Koran was respected after officers were accused of desecrating the text, including allegedly flushing the book down the toilet to torment prisoners.

But fear of Muslim personnel at Guantánamo was pervasive. Commanding officers were afraid they might engage in whistleblowing.

On September 10, 2003, Yee was arrested because the military believed he was part of a “spy ring.” (In January 2005, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published the definitive account by Ray Rivera of what happened to Yee.)

Investigators developed a conspiracy theory that Yee and his Muslim colleagues used the “library to run a secret communication network for detainees and to pass along subversive literature to help them resist interrogations.” News headlines alleged that he engaged in "espionage" and “aided the enemy.”

Ahmad al-Halabi, an intelligence linguist at Guantánamo, was also arrested and accused of similar offenses.

Though the case collapsed by November, Yee was held in solitary confinement for 76 days. Authorities kept him in shackles and leg irons. He was treated much like prisoners he provided spiritual guidance.

The military further smeared his character after they realized they had no espionage case. He was charged with “downloading pornography from the internet, making a false official statement, and adultery,” before finally receiving an honorable discharge.

While Yee was stationed at Guantánamo, Major General Geoffrey Miller was the commander. He was notorious for backing the use of torture and abuse against prisoners and later was in charge of Abu Ghraib prison, the site of a torture scandal in 2004.

Yee wrote a memoir that was published in 2005, For God and Country: Faith and Patriotism Under Fire. In addition to recounting the political case the military tried to bring against him, he detailed physical, sexual, medical, legal, religious, and psychological abuse that he observed.

“Some of the translators who worked in the [Joint Interrogation Group] told stories about female interrogators who would take off their clothes during the sessions. One was particularly notorious and would pretend to masturbate in front of detainees,” Yee recalled.

“She was also known to touch them in a sexual way and make them rub her breasts and genitalia. Guards were apparently instructed to stand behind the prisoner and pull their cheeks and eyes back, trying to force them to watch,” according to Yee.

“Detainees who resisted were kicked and beaten. A translator who worked interrogations who had witnessed this woman’s behavior told me that her supervisor had told her to tone down the tactics but had not disciplined her.”

Like Saar, Yee witnessed IRF’ing and was stunned by the “open and violent display of strength versus weakness":

Under the direction of a noncommissioned officer, they gathered quickly and put on riot protection gear—helmets with plastic face guards, heavy gloves like those a hockey goalie wears, shin guards, and a chest protector […] After they suited up, they formed a huddle and chanted in unison getting themselves pumped up. Then they rushed the block, one behind the other, where the offending detainee was […] The IRF team stopped at the detainee’s cell and lined up in single file outside it. The team leader in front drenched the prisoner with pepper spray and then opened the cell door. The others charged in and rushed the detainee with the shield as protection. The point was to get him to the ground as quickly as possible, with whatever means necessary—shields, boots, or fists.

It didn’t take long: no detainee was a match for eight men in riot gear. Three of the guards used the full force of their shields and bodies to hold the prisoner down. One tied the detainee’s wrists behind his back and then his ankles, using strong plastic ties rather than the standard metal cuffs. The guards then dragged the detainee from his cell and down the corridor. As he lay in a bruised heap on the floor, the guards stopped to catch their breath and drink water that the other guards brought for them.

They then continued to drag the man to solitary confinement. When it was over, there was a certain excitement in the air. The guards were pumped, as if the center had broken through the defense to score the winning goal. They high-fived each other and slammed their chests together, like professional basketball players. I found it an odd victory celebration for eight men who took down one prisoner. I felt uncomfortable for the rest of the day. I wasn’t accustomed to seeing such an open and violent display of strength versus weakness.

Yee recognized exactly why he was targeted, even demeaned as “Chinese Taliban.”

“I was bringing to the command the issues that the prisoners had with regard to how they were being mistreated, abused, and tortured. So I was formally trying to address that the way a military officer should, and some people didn’t like that, and they wanted me out.”

Three Deaths And A Cover-Up Orchestrated By The Command

On June 10, 2006, the New York Times reported that three detainees held at Guantánamo committed suicide. Rear Admiral Harry B. Harris Jr., who was the commander at Guantanamo, claimed the deaths were “discovered” after a “guard noticed something out of the ordinary in a cell and found a prisoner had hanged himself.”

“Guards found two other detainees in nearby cells had hanged themselves as well. All were pronounced dead by a physician,” according to Harris.

Immediately, U.S. military officials cast the suicides as a “form of coordinated protest” by “terrorists.”

“They are smart. They are creative. They are committed," Harris declared. "They have no regard for life, neither ours nor their own. I believe this was not an act of desperation but an act of asymmetrical warfare waged against us."

The Times published a follow-up a day later that repeated the narrative of the U.S. military, which was that the suicides were part of a “ruse.” The detainees supposedly concealed themselves in their cells to prevent guards from seeing them take their own lives.

However, Joseph Hickman, was on duty as a staff sergeant for Camp America’s security force during the night the “suicides” occurred. He shared his observations with journalist Scott Horton and blew the whistle on what happened to Mani al-Utaybi, Yasser al-Zahrani, and Ali Abdullah Ahmed. (Both al-Utaybi and al-Zahrani were scheduled to be released to Saudi Arabia, their home country.)

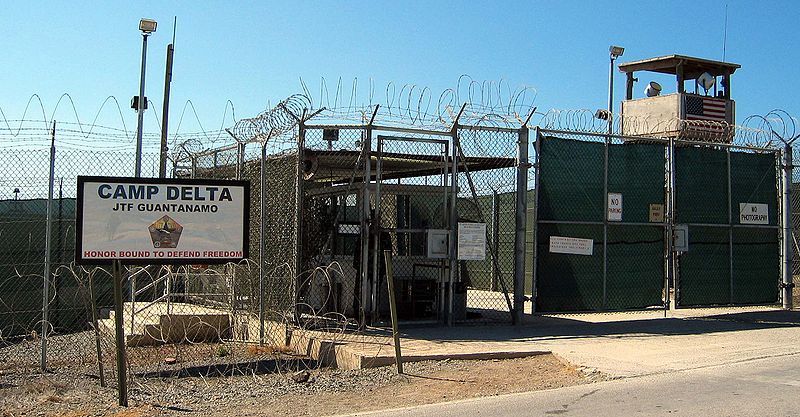

“I witnessed three detainees leave the camp in a white van and be transported to a top secret CIA facility, only to return to the camp a few hours later—dead,” Hickman recalled. “Over the next few hours, after the bodies returned to Camp Delta, I watched a cover-up being orchestrated by the GTMO Command.”

“My commander flat-out lied to the media about what happened, claiming the detainees committed suicide in their cells as a form of asymmetrical warfare,” Hickman added.

Hickman told Horton he saw the white van take the detainees to “Camp No,” and upon return to Camp America, the van went straight to the medical clinic.

Accounts spread in in the detention camp that the detainees died by “choking on cloth.” The camp’s commanding officer echoed this account and told a “gathering of personnel” the next day that the “prisoners died by choking on cloth, but that an official account would soon be released saying that they had committed suicide by hanging themselves.”

“All present were ordered not to contradict or undermine the official account in any way,” according to the report from Horton.

“Even though going against the U.S. military’s official story of what happened that day would most assuredly end my military career, it was my duty as a soldier to report it,” Hickman declared. “I went to the U.S. Army Inspector General and the Justice Department and reported what I witnessed. After I reported it to the Justice Department, they opened an official investigation and the FBI spent almost a year looking into my allegations.”

“They finally contacted my attorney and told him that while ‘the gist of what I reported was true,’ they were closing the case, and were not going to pursue any charges against those involved.”

Hickman left the military after that decision and wrote a book, Murder at Camp Delta: A Staff Sergeant’s Pursuit of the Truth About Guantánamo Bay, that was published in 2015. It provided more details from that night in the hopes that the investigation into the detainees’ deaths would be reopened.

'The Guantánamo Files' Further Unravel The Biggest Lies About The Military Prison

In 2009, U.S. Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning stumbled upon a set of detainee assessment briefs for over 700 Guantánamo Bay prisoners. She did not think too much of them at the time, but she came back to them in early 2010.

“I have always been interested in the issue of the moral efficacy of our actions surrounding Joint Task Force Guantánamo,” Manning told a military judge during her court-martial. “[I] understood the need to detain and interrogate individuals, who might wish to harm the United States and our allies.”

But she added, “The more I became educated on the topic, [the more] it seemed that we found ourselves holding an increasing number of individuals indefinitely that we believed or knew to be innocent, low-level foot soldiers that did not have useful intelligence and would be released if they were still held in theater.”

The assessments showed children and elderly men were imprisoned. Al Jazeera journalist Sami al-Hajj was sent to Guantánamo in order to force him to “provide information” on “al Jazeera news network’s training program, telecommunications equipment and newsgathering operations in Chechnya, Kosovo, and Afghanistan, including the network’s acquisition of a video of [Osama bin Laden] and a subsequent interview” of bin Laden.

“Information on the first 201 prisoners released between 2002 and 2004,” according to journalist Andy Worthington, “had never been made public before. The majority of the new documents revealed accounts of incompetence, with innocent men detained by mistake, or because the U.S. was offering substantial bounties to its allies for ‘al Qaida’ or ‘Taliban’ suspects.”

As Worthington elaborated in a statement submitted as part of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s defense during his extradition hearing, “The documents showed that the testimony of witnesses was central to the justification of detention,” and, “in the majority of cases the witnesses were the Guantánamo prisoners’ fellow prisoners who had been subjected to torture or other forms of coercion either in Guantánamo or in secret prisons run by the CIA, or equally unreliable because fellow prisoners had provided false statements to secure better treatment in Guantánamo.”

In 2013, Manning was found guilty of violating the Espionage Act when she disclosed the Guantanamo files. She spent six years in a military prison before her sentence was commuted by President Barack Obama.

The transfer and publication of files factored into the indictment against Assange, which charged him with aiding and abetting a leak in alleged violation of the Espionage Act in 2019. It was the first time a journalist was charged under the World War I-era law.

Comments ()