Trump Administration Is Using The 'State Secrets Privilege' Just As It Was Intended

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers of The Dissenter. Become a subscriber and support independent journalism on government secrecy and freedom of the press.

President Donald Trump’s administration invoked the “state secrets privilege” to prevent a United States court from reviewing the abduction of immigrants, mostly Venezuelans, who were flown to El Salvador and Honduras.

A number of explainers related to the Venezuelan migrants case have been written about the state secrets privilege. One in particular from CNN suggested that Trump had broken with “past practice.” Most of them gloss over or omit similarities between this case and the 1953 case known as U.S. v. Reynolds, which established the state secrets privilege.

The fact is, despite Trump’s assertion of executive power and the denials of due process, officials are employing the state secrets privilege just as officials have for decades—to perpetuate government deception and fraud and to shield agencies and their officials from accountability.

On March 15, Trump officials removed 261 people from the U.S. while attorneys from the American Civil Liberties Union were pursuing an effort in court to halt their removal. The Trump administration said 137 of them were “deported” under the Alien Enemies Act because they were allegedly part of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

U.S. District Judge James Boasberg of the D.C. Circuit barred the Trump administration from invoking the Alien Enemies Act and ordered officials to turn the flights around. When they failed to return the immigrants, he demanded information related to the flights.

On March 24, the Justice Department (DOJ) officially invoked the state secrets privilege [PDF].“The Court has all of the facts it needs to address the compliance issues before it. Further intrusions on the Executive Branch would present dangerous and wholly unwarranted separation-of-powers harms with respect to diplomatic and national security concerns that the Court lacks competence to address.”

“Accordingly, the states secrets privilege forecloses further demands for details that have no place in this matter,” Attorney General Pam Bondi and other top DOJ officials added.

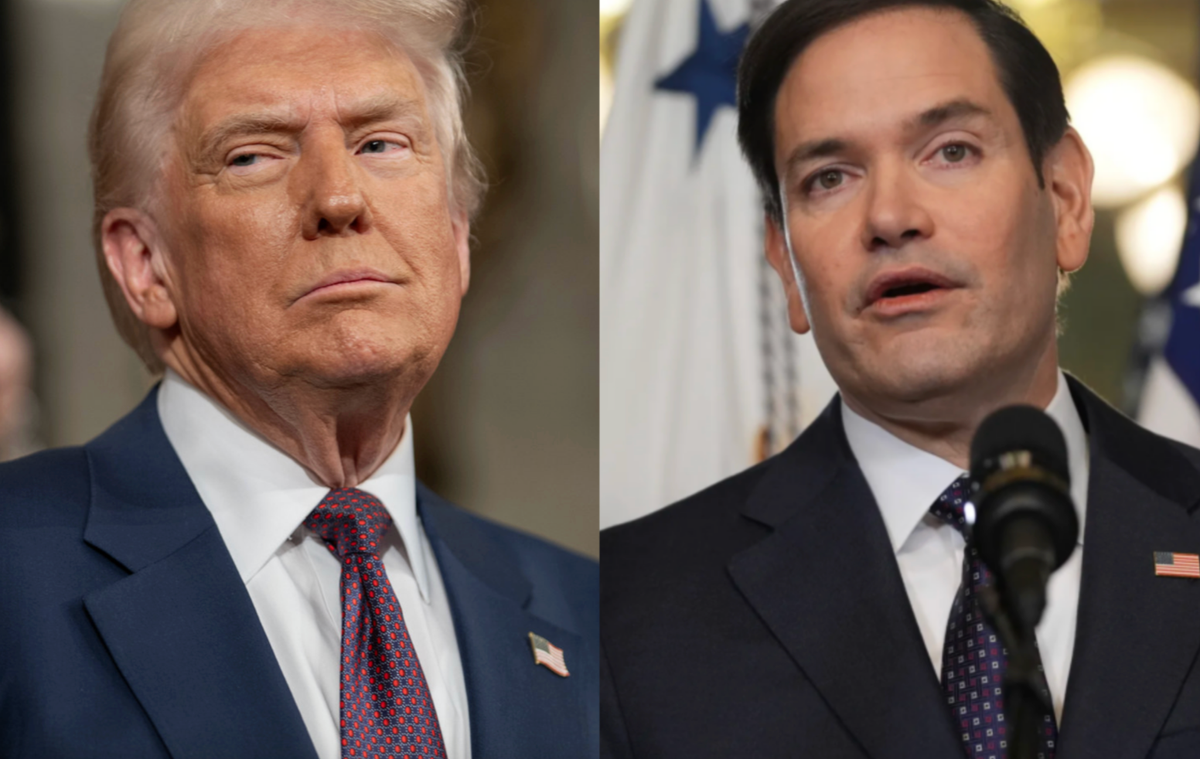

Declarations by Bondi [PDF], Secretary of State Marco Rubio [PDF], and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem [PDF] rejected the court’s request for information on the “time the planes took off and from where,” the “time the planes left U.S. airspace,” the “time the planes landed, where they landed, and whether they made more than one stop,” when the individuals were transferred out of U.S. custody, and how many individuals were aboard the flights.

Often the U.S. government provides a summary of the information at issue to help demonstrate to the court that disclosure would jeopardize national security or foreign policy interests. Yet like the Reynolds case, Bondi and the DOJ flatly refused to show the court any of the supposed secrets.

Avoiding Liability For A Military Aircraft Accident

The widows of three civilian engineers, who died in a B-29 Superfortress bomber crash in 1948, sued the U.S. Air Force a year later. They sought damages in a U.S. court in Philadelphia, and the effort hit a roadblock when the Air Force refused to turn over accident investigation reports.

After the U.S. Supreme Court recognized this extraordinary “claim of privilege,” the widows accepted a settlement rather than continue the case. But in 2000, one widow, Patricia Herring (previously Reynolds), learned that the Air Force accident investigation reports were declassified. She finally had evidence of the fraud that the government had perpetrated. Along with children of the two other widows (now deceased), Herring petitioned [PDF] the Supreme Court to remedy this fraud.

As the complaint recounts, on October 9, 1950, the district court once again ordered the government to produce the accident investigation reports in addition to witness statements. The U.S. government defied this order, and the court held the government “liable for damages.” An appeal was then filed with the Third Circuit Court of Appeals that further insisted “federal courts should review such claims of privilege [in private] in order to evaluate their validity and proper scope.”

In 1952, the U.S. government appealed to the Supreme Court and went beyond the initial claim of privilege. Officials maintained that “the executive branch might lawfully withhold any document from judicial scrutiny if it deemed secrecy in the public interest.” Representations by Secretary of the Air Force Thomas K. Finletter and Major General Reginald C. Harmon, the judge advocate of the general of the Air Force, were considered enough to uphold secrecy.

“[W]hen the formal claim of privilege was filed by the Secretary of the Air Force, under circumstances indicating a reasonable possibility that military secrets were involved, there was certainly a sufficient showing of privilege to cut off further demand for the documents on the showing of necessity,” the Supreme Court decided.

Harmon asserted that the bomber “carried confidential equipment on board and any disclosure of its mission or information concerning its operation or performance would be prejudicial to the Department and would not be in the public interest.” Furnishing any of the information at issue would supposedly hamper “national security, flying safety and the development of highly technical and secret military equipment.”

Yet representations by officials were false. The documents never described a “secret mission” or referred to newly developed electronic devices. They instead focused on what led to the crash, including how the Air Force failed to install heat deflector shields. The government had been deceitful during discovery when officials asserted that there were no modifications “prescribed” for the aircraft prior to the accident.

Negligence was also confirmed. The files indicated that the engineers had not been briefed on emergency and aircraft evacuation procedures, which the Air Force required.

Adopting A Stance Popular In Cases Against The CIA

Much like Finletter or Harmon, it is clear that Trump officials are obfuscating the truth. Rubio contended in his declaration that the “[c]ompelled disclosure of the number of aliens aboard any deportation flight…and the reasons any of those aliens were placed aboard the deportation flight, threatens significant harm to the United States’ foreign affairs and national security interests.”

“For example,” Rubio continued, “if compelled disclosure of that information came to light, it could cause the foreign State’s government to face internal or international pressure, making that foreign State and other foreign States less likely to work cooperatively with the United States in the future, both within and without the removal context.”

However, Rubio voluntarily revealed El Salvador’s enthusiastic cooperation in a press statement on March 16. “I want to express my sincere gratitude to President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador for playing a pivotal role in this transfer. He has volunteered to imprison these violent criminals.”

The Miami Herald additionally reported that Bukele had confirmed that "238 Venezuelan migrants deported from the United States had been 'immediately transferred to the Terrorist Confinement Center,’ a mega-prison Bukele built as part of his country's crackdown on organized crime. He circulated a video showing heavily-armed guards with covered faces forcing cuffed immigrants along as they were moved to the facility. Rubio also reposted the video and thanked Bukele for his ‘assistance and friendship.’”

Nonetheless, the argument deployed by Rubio to prevent court oversight is notable because the CIA deployed an identical argument to keep information related to the CIA’s rendition, detention, and torture of “war on terrorism” captives a secret.

Abu Zubaydah, a high-profile detainee at Guantanamo Bay, was tortured by the CIA. He attempted to subpoena James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, both architects of the agency’s torture program who interrogated him at a black site in Poland. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled [PDF] in 2020 that the state secrets privilege did not cover all of the information sought by Zubaydah. The government on behalf of the CIA asked the Supreme Court to overturn the decision.

“The [CIA] Director stated that it is ‘critical’ to national security to protect the ‘location of detention facilities’ and ‘the identity of foreign partners who stepped forward in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks,’ because those partners ‘must be able to trust our ability to honor our pledge to keep any clandestine cooperation with the CIA a secret,’ even after ‘time passes, media leaks occur, or the political and public opinion winds change.’”

Also, “The CIA’s ability to ‘convince foreign intelligence services to work with us,’ [the Director] explained, depends on ‘mutual trust’ and ‘our partners’ confidence that their role will be protected even if new ‘officials come to power’ who may ‘want to publicly atone or exact revenge for the alleged misdeeds of their predecessors.’”

On March 3, 2022, the Supreme Court issued a 7-2 opinion [PDF] in favor of the government and expanded the state secrets privilege. “The CIA’s refusal to confirm or deny its cooperation with foreign intelligence services plays an important role in and of itself in maintaining the trust upon which those relationships are based,” wrote Justice Stephen Breyer, who authored the opinion.

Breyer referred to the Reynolds case and maintained that there was no legal requirement to show a judge the information at issue. He insisted the CIA director’s affidavit was “sufficient” to grant the government’s claim of privilege.

The State Secrets Privilege Has Always Been A Shield

Mark Zaid, a national security lawyer in Washington, D.C. “who has litigated state secrets privilege cases,” told CNN that the claim of privilege was a “bolder assertion than what the Executive Branch normally takes,” and that it represented an “effort to use the privilege as a shield instead of a sword, because they have run out of options.”

However, anyone with knowledge of the state secrets privilege should know that this is incorrect. The privilege has always been used by U.S. government agencies as a shield to avoid accountability for criminal allegations or human rights abuses.

Consider these cases where the state secrets privilege was successfully invoked:

—racial discrimination against a CIA whistleblower Jeffrey Sterling, who initiated proceedings challenging his treatment in the workplace (Sterling v. Tenet)

—sex discrimination by the CIA in the workplace (Tilden v. Tenet)

—workplace retaliation at the FBI for whistleblower conduct after a translator uncovered infiltration by foreign agents (Edmonds v. Department of Justice)

—warrantless eavesdropping by the CIA, State Department, and another government agency against a Drug Enforcement Agency agent stationed in Burma (Horn v. Albright)

—the extraordinary rendition of an individual from the U.S. to Syria (Arar v. Ashcroft)

—the abduction, beating, drugging and transportation of an individual to a secret CIA prison in Afghanistan (El-Masri v. Tenet)

—dragnet surveillance by the NSA (Shubert v. Obama, Jewel v. NSA)

—warrantless surveillance of communications of customers of a private corporation (Hepting v. AT&T)

—the placement of a U.S. citizen on a kill list (Al-Aulaqi v. Obama)

—spying on American journalists and attorneys who visited WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange (Kunstler v. Pompeo)

—the CIA's rendition and torture of British resident Binyam Mohamed and four other survivors (Mohamed v. Jeppesen Data Plan)

—the murder of an American community worker by U.S.-supported Contras in Nicaragua (Linder v. Calero)

The deception and fraud in the Venezuelan migrants case may seem more blatant than prior cases, where state secrets were claimed, yet that may prove to be inconsequential because for 70 years the judicial branch has facilitated the expansion of what amounts to a get out of jail free card.

Evidence shows that several of the individuals whisked away and imprisoned in El Salvador were falsely accused of being Tren de Aragua members. “J.G.G.” [PDF] is a tattoo artist, and he had tattoos of an eye and a rose and skull that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) singled out. Neither of the tattoos signify his membership in the Venezuelan gang.

“W.C.G.” [PDF] actually “fled Venezuela and requested asylum” in the U.S. because they were “being extorted and threatened by multiple criminal groups including Tren de Aragua.” “J.A.V.” [PDF] was also “victimized” by Tren de Aragua and fears returning to Venezuela.

The government is aware of the problem of relying on tattoos. USA Today reported on a 2023 “Situational Awareness Bulletin” from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s El Paso Sector Intelligence Unit that stated, “Tattoos are typically related to the Venezuelan culture and not a definite [indicator] of being a member or associate” of Tren de Aragua.

The threat of Tren de Aragua has been incredibly hyped, with the Trump administration even going so far as to designate the group a “foreign terrorist organization.” But as outlined by The Guardian’s South America correspondent Tiago Romero, officials exaggerate the danger posed by this gang to reinforce their mass deportation agenda.

Regardless of everything that is known, a Trump Cabinet official submitted a declaration that state secrets are "at risk." That may be enough to prevent accountability. According to Shayana Kadidal, a human rights attorney for the Center for Constitutional Rights who has experience fighting state secrets claims, "[A]s long as they can get a cabinet official to sign off (personally) to a declaration, game over."

Comments ()