The Loving Truth-Teller That Was Daniel Ellsberg

Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower and peace activist who released the Pentagon Papers that exposed the Vietnam War, has died at the age of 92. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer on February 17, and doctors gave him three to six months to live.

He was a subscriber to The Dissenter Newsletter. So it is only appropriate that I share some of my personal memories in honor of who he was and because he meant so much to so many people.

Nearly two weeks after his diagnosis, Dan messaged his friends and supporters. That message was republished by various news media outlets as it circulated.

“I feel lucky and grateful that I've had a wonderful life far beyond the proverbial three-score years and ten,” Dan wrote. “I feel the very same way about having a few months more to enjoy life with my wife and family, and in which to continue to pursue the urgent goal of working with others to avert nuclear war in Ukraine or Taiwan (or anywhere else)."

Dan mentioned that his cardiologist had given him permission to abandon his salt-free diet, and that his energy level was high. He had done “several interviews and webinars on Ukraine, nuclear weapons, and first amendment issues.” He had two more scheduled interviews.

One of those interviews was with me. In fact, around the same time that Daniel learned that he had cancer, I contacted him to ask if he would help me with the launch of my book, Guilty of Journalism: The Political Case Against Julian Assange. He already had given me a blurb for the book.

Dan graciously agreed to talk with me once again about the Assange case. He even asked for a hard copy so that he could review the book. My publisher Censored Press quickly mailed a copy to him, and we planned to record on Wednesday, March 1.

That became the day that friends and supporters of Dan were notified by him that he had cancer.

When it was time for us to do the interview, Dan called me. He had not had a chance to read my book yet. Dan wanted to know if he could have a couple of hours to read the book and then we would record the interview. He even asked, which chapters should I read?

I had asked Dan for an interview simply because I believed posting a conversation the same day that my book was released would help me get the attention of potential readers. I did not need him to prepare for the interview by familiarizing himself with specific sections of the book, and yet, that’s what Dan was willing to do because he was a generous person.

The attention Dan gave to you was a sign of the love and respect that he had for those who were willing to fight for the same causes that were crucial to him.

Dan logged on to record, but before he would allow me to start the interview, he brought up a couple errors, which he had identified in my book.

The first error was in this paragraph from “The Abusive Grand Jury” chapter.

After Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, who worked for the RAND Corporation, provided copies of the Pentagon Papers to media organizations, the DOJ convened two grand juries in the Boston area—one in April 1971 that did not return any indictments and another in August 1971.

Dan flatly told me that a grand jury investigation in April 1971 would have been impossible. I definitely was wrong, but I later showed him a declaration with his name on it that came from a lawsuit to force the release of grand jury records. It mentioned an April grand jury.

“Ha ha! However, Kevin, that still doesn't make sense, even if I said it,” Dan replied. According to Dan, law school students working with historian Jill Lepore, who filed the lawsuit, must have drafted the declaration. “It's clear to me that I at least edited it, as well as signed it,” but that did not make the April date correct.

The second error was in the chapter on “Standard News-Gathering Practices”:

Thomas Kauper of the OLC advised White House Counsel John Dean that the Espionage Act would allow newspapers, and even “individual reporters,” to be prosecuted. Kauper further suggested the New York Times could be criminally charged for conspiring and encouraging the theft of the Pentagon Papers. But the US Supreme Court rejected the Nixon administration’s view and refused to issue an injunction against the Times or the Washington Post.

I had written a non sequitur. The Supreme Court did not rule on how far the Nixon administration could go in pursuing journalists for publishing leaks. The Supreme Court ruling only applied to prior restraint—whether the government could stop a newspaper from reporting on the Pentagon Papers. On that question, the Supreme Court decided the answer was no.

But Dan was unaware of the advice from Kauper and was excited to learn about the Office of Legal Counsel memos reported by Reuters in June 2022.

“Fascinating! I have to be selective in what investigations I want to prioritize in my remaining month(s), but this will be among them!” Dan wrote. He planned to read as much as he could about the memos, and see what John Dean remembered. “Nothing could be more relevant to the Assange case!”

As we talked about the two sections of my book, Dan was tired and confused. He kept asking me over and over again about these parts, even though I had acknowledged the errors. It was the first time in my interactions with Dan—aside from some hearing problems—that his age really showed. Usually, he was cognitively sharp. We both recognized that it would be best to push our recording session to Friday.

Not Able To Sleep

On Friday, Dan was awake until 4 or 5 a.m. While he could not sleep, he read part of my book and a feature story in Harper’s Magazine from Washington, D.C., editor Andrew Cockburn that detailed how the media had failed Assange. Cockburn’s feature praised my coverage of both the Assange and Chelsea Manning’s cases as examples that other journalists should have followed. Dan called the feature “sensational” and said, “We must discuss it.”

We talked for two hours. Before we officially started the interview, Dan went chapter-by-chapter to inform me of what he had read. “I’m kind of rundown, I’m afraid. It’s not the best day, like the other day,” Dan said. From 1:30 to 2:30 a.m., he was up reading my chapter on the Espionage Act “very carefully.”

Dan asked why I omitted many of the details related to the Swedish extradition case from the book. While we discussed my reasons (the sexual allegations were not part of the U.S. case against him), Dan mentioned that he had spoken to Assange about the allegations. Assange had accepted that he behaved in an “ungentlemanly” manner with the two women. And though he did not deserve to be criminally charged, Assange recognized how his actions might lead someone to view him as a “chauvinistic pig.”

“What is your personal opinion of the Russiagate allegations?” Dan had not had a chance to read the Russiagate chapter, but he was interested in my position.

After we went back and forth on Assange’s claim that he had not received the Clinton campaign emails from a “state party,” Dan commented on Trump adviser Roger Stone, who repeatedly exaggerated and fabricated claims about his communications with WikiLeaks.

“[Roger] Stone was once involved in an incident [on the steps of Capitol Hill] that was supposed to incapacitate me. We won’t go into that, but on May 3, [1972]—he was a young guy then—he brought a bunch of college students to provide an uproar as cover for CIA assets, who were to incapacitate me.”

Dan was in rare form during our recorded interview. The moment I started asking questions he was energized. We spoke for nearly two hours, and he never told me that I needed to end the interview. I probably could have talked with him for another half hour if I wanted.

Multiple times Dan paused. A glimmer appeared in his eyes as he chimed, “Okay, I’ll tell you something I’ve never said publicly.” Then he would share an extraordinary anecdote. Or he would acknowledge that he was “coming to a point,” where he did not have to worry about “antagonizing” a media organization or particular media figures. So Dan would call them out.

Before Dan signed off, he revealed how he had made it through the interview. He had eaten a bunch of chocolate. I told Dan I would see him later, and he gave me an odd look. We knew we would never speak to each other again.

The Joy Of Living Life As An Unapologetic Truth-Teller

I first met Dan in December 2011, when Firedoglake editor-in-chief Jane Hamsher asked me to drive him to her house in Washington, DC, after a pretrial hearing at Fort Meade in Chelsea Manning’s case. He did not know anything about me, and yet I was invited by Alyona Minkovski to come to RT’s DC studio for her show.

That left me no choice. I asked the RT producers if I could bring Dan and have him appear on the air with me. We appeared together, but the clip is no longer available on YouTube because all RT content was removed after Russia invaded Ukraine. Dan was courteous enough to appear with me, even though we barely knew each other.

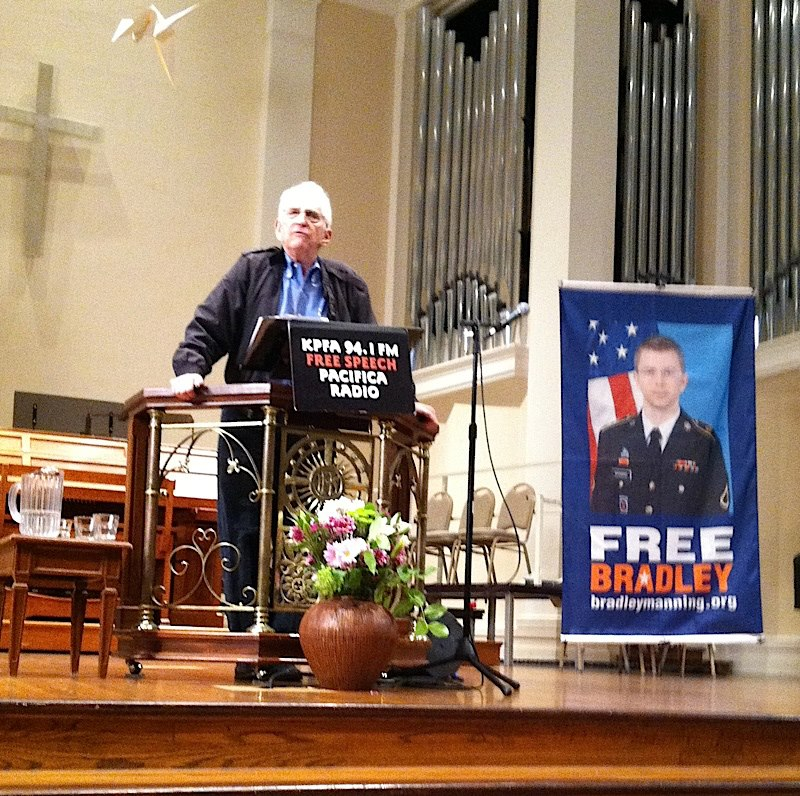

On January 31, 2013, I opened for Dan at the First Congregational Church in Berkeley, California. The event was sponsored by KPFA, a community radio station, and Dan spoke about his case, Manning’s case, Brown & Williamson tobacco whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand’s case, and other cases, where whistleblowers revealed crimes and misconduct.

Months later, on September 20, Dan welcomed me into his home for an interview. He showed me his library, where he kept all his private papers, and when I told him I had not seen “The Most Dangerous Man In America,” the 2009 documentary about his whistleblowing, Dan gave me a DVD copy.

We walked to lunch after the interview, and Dan shared his wisdom on an array of topics. He also was interested in what I had to say from my experience covering the military trial against Chelsea Manning and wondered what life in Chicago was like under Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

There were a few more times that I spoke with him. When he released his book, Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear Planner, I made certain that I had a chance to talk with him. He was part of a panel discussion that I hosted for the Assange Defense Committee in January 2021.

Just prior to his cancer diagnosis, I asked if we could do a book event together in Berkeley, California. He responded, "With the greatest respect to you and [a] desire to see your book do as well as you deserve, I take it this means an in-person event, and I haven't done those for three years, due to Covid concerns."

At the end of our final conversation, I said something to Dan about the fact that he had an opportunity to prepare for his death and say farewell to all the people that he wanted. I believe that Dan was very fortunate because my father died from a heart attack when he was 56 years old (I was only 26 years old).

Seeing Dan's life announcement, and the warm responses to it, made it easier for me to accept that one of the best human beings I have ever known had come to the end of his life.

Dan was not at peace with the world around him. Wars and the threat of nuclear armageddon motivated him to do several more interviews while he could still speak with reporters. But he did feel joy and gratitude having lived his life unapologetically as a peace activist and truth-teller—someone who embodied the idea of the moral imperative.

For the rest of my life, I will cherish the fact that I was one of the first journalists who Dan spoke with on his farewell media tour and that I had the privilege of interacting and sharing his wisdom with the world for over a decade.

Comments ()