The Assange Prosecution: A Haunting Reminder Of What Happened In My Espionage Act Case

Guest contributor Jeffrey Sterling, a CIA whistleblower, responds to how his case has been invoked by prosecutors to help them win the WikiLeaks founder's extradition

By Jeffrey Sterling

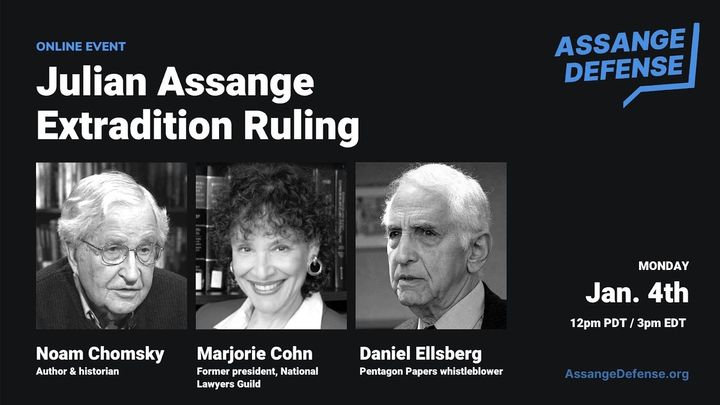

The prosecution against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has invoked my case, making it a haunting reminder of the travesty of justice that befell me.

I worked for the Central Intelligence Agency. In 2015, the United States government wrongfully tried, convicted, and sent me to prison for allegedly violating the U.S. Espionage Act. I am one of the few who has ever gone to trial to defend their selves against this ancient and misused law.

If I had succeeded in defending myself, it is possible Assange may not be facing the same impossible hell that ruined my life. As such, I feel a burden to challenge certain statements by the Crown Prosecution Service in Assange’s case.

Sentencing and prison conditions have been key issues during proceedings in the United Kingdom.

At the extradition trial in September, Crown prosecutor James Lewis noted I was sentenced to 42 months in prison, even though I took my case to trial. Lewis brought up the case to inappropriately argue that I was prosecuted fairly and Assange is unlikely to be sentenced to decades in prison.

I find the use of my name and the travesty of justice that was my trial to be an insult to both the sensibilities of justice and truth.

On top of that, one of the biggest lies is the prosecution’s assertion that I provided plans and documents to a reporter, which I did not do. In fact, this was not a part of the case against me—at all.

The truth of the matter is, the prosecutor in my case was absolutely livid that my sentence was only 42 months. The U.S. government wanted me to spend far more time in prison, much closer to the maximum 100-year sentence I faced.

Judge Leonie Brinkema in the Eastern District of Virginia (EDVA), the same district where Assange may face trial, did not hand down my sentence out of any innate benevolence., It was more a result of a begrudging realization of the injustice that resulted in my conviction.

There will be no offer of reasonableness for Assange from either the U.S. prosecutors or the judge. He will be handed the maximum sentence allowable.

And if anything, my case should serve as a warning that the U.S. government will use the Espionage Act and a biased court to extend its vengeance to reach voices of dissent not only in the U.S. but also anywhere in the world.

Effectively Blackballed After Going To Committees In Congress

While working at the CIA, I was a clandestine operations officer specializing in Iran. I speak Farsi and worked subjects related to Iranian politics, regional dynamics, and weapons of mass destruction. I was good at my job, but to the CIA, I had the wrong skin color. The answer to my question as to why I was not receiving the same opportunities as every other officer at the CIA was that I would stick out as a big black guy speaking Farsi.

In 2001, I became one of the only African American clandestine officers to ever sue the CIA for racial discrimination. President George W. Bush’s Justice Department argued my lawsuit would jeopardize state secrets, and the EDVA blocked my civil rights complaint. This was the first time the court treated me like a terrorist.

I also was part of Operation Merlin, which was an ostensible effort to hamper Iran’s development of a nuclear weapons program. The CIA assured me the operation was safe and plans we provided were flawed so they would undermine Iran. Yet, I became concerned that safety protocols were not what the agency had promised, and after the invasion of Iraq, I dreaded the operation could be used against U.S. soldiers.

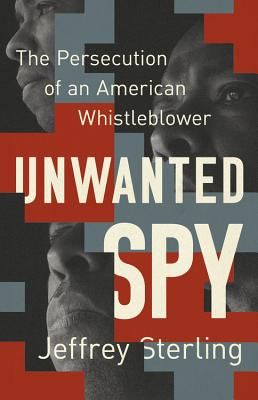

Following whistleblower procedures, I took my concerns to both the Senate and House intelligence committees. Despite their assurances of confidentiality and initial responses to my concerns, neither committee saw fit to act on my disclosures. (For more background, I encourage you to read my book, Unwanted Spy: The Persecution of an American Whistleblower.)

The CIA eventually fired me, and I lost everything. I could not find a job despite my expertise in both Iran and terrorism, during a time when my government was desperate for such resources. No government agency or contractor would hire me, which meant I was effectively blackballed. (The American intelligence community has a long and vengeful memory.)

After years of struggle, I moved to a new state, had a new job, and found love. I believed the turmoil with the CIA was over for good.

Out of the blue, the FBI raided my home. I was under investigation for leaking information related to Operation Merlin to a reporter who put that information in a book. And to emphasize the heights retaliation can take, I was eventually arrested in January 2011 and charged with violating the Espionage Act.

The Shock Of Facing Prosecution Under the Espionage Act

Being tried under the Espionage Act was an experience that destroyed every reasonable notion I ever had about law, government, fairness, and justice in the United States. The initial shock was being branded a traitor by my government.

The arrest left me confused and angry. I never divulged classified information to anyone who was not authorized to receive it. But in a tragic sort of way, it all made sense. I was the only black face involved in Operation Merlin. I was the only individual to complain about the dangers of the operation, and I had the nerve to sue the CIA for discrimination.

I was a spy for my country, not against it. I did not speak to any reporter nor did I ever divulge any classified information to anyone not authorized to receive materials. All I did was stand up for the rights I was guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution and oppose a reckless CIA operation by going to the appropriate government intelligence committees.

Yet, I found myself jailed in the same cell block of the Alexandria jail that held infamous 9/11 conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui and accused of a crime I did not commit. It was clear that my government viewed and would treat me as a terrorist.

The next shock was facing trial in the same court, the EDVA, which had previously determined I had no rights as a citizen to challenge how my government discriminated against me.

How the EDVA viewed me was made clear early on when I argued for release from the Alexandria jail. Prosecutors maliciously claimed if I was released I was bound to undertake a murderous spree against CIA employees. During the proceeding to determine whether I was to be released, an old friend who lived in Virginia stood up to attest to my character.

There was no real justification to keep me in the Alexandria jail, yet Brinkema found another way to continue the persecution. With no real expressed authority to do so, Brinkema ordered my friend to give me a place to stay. If my friend did not acquiesce and post a $10,000 bond, I would remain in the Alexandria jail. My friend had no choice but to accept Brinkema’s unjust terms.

I was thankful to have such a wonderful friend, but that release from the Alexandria jail kept me separated from my family at a time trying to defend myself.

A federal judge is unlikely to show this sort of supposed benevolence to Assange. He will most likely be held in the same cell block that I was in at the Alexandria jail until and during a potential trial.

Assange Will Face A Potentially Severe Prison Sentence Like I Did

Should Assange be extradited and put on trial in the EDVA, he will face the same terminal decision I faced: whether to go to trial and risk an unending sentence or plead guilty to a crime created by and imposed on him by the U.S. government.

My trial began in January 2015, and everything I learned in law school about trials and criminal procedures seemed to mean nothing to the Department of Justice prosecutors as well as the EDVA.

The EDVA is a court notorious for siding with the government, and the jury pool consisted of individuals, who either had a U.S government security clearance or maintained a close connection with those who did. That set me up for a battle with the jury in addition to the prosecutors and the judge.

I can certainly understand why anyone facing such a situation under the Espionage Act would plead guilty to take the prospect of a long prison term off the table. U.S. prosecutors are known for making threats of extensive prison terms against defendants if they take their cases to trial.

Even though I faced 10 years for each of the 10 counts against me—roughly 100 years in prison if I were convicted—pleading guilty to crimes I did not commit was out of the question.

Interestingly, the prosecution never made any efforts to negotiate a sentence with me (not that it would have mattered), though they did indicate they wanted me to plead to something.

If there was any indication that this trial and prosecution was more about retaliation and the CIA saving face, that was all the proof I needed.

Worse Prospects For Justice

Justice delayed is justice denied is an often ignored legal maxim. My persecution by the U.S. government extended for several years.

Despite being arrested in 2011, my trial did not happen until four years later. Though I was not in prison awaiting the intentionally slow legal process, I was left in a terrible limbo. I clung to not only keeping my life together but also to the notions of justice, which I had grown up with and studied.

Assange has already spent close to two years in a U.K. prison. He’s endured a decade of arbitrary detention in the U.K, and if he is extradited, he will remain confined, putting his already fragile health in jeopardy.

When the time came for my trial, it was a fiasco. There were days of testimony attesting to how well the CIA conducts operations in a clear move to counter the assertions made about the spy agency and its competence.

The government paraded witness after witness in front of the judge to testify that they had access to Operation Merlin—only to claim they never had contact with any reporter or released classified information to anyone not authorized to receive it. Yet, I was not able to challenge the witnesses or even the validity of the government’s case against me.

Barry Pollack, an attorney who represented me and is now part of Assange’s legal team, says Assange’s prospects are worse. In my case, I had access to all the information presented in the case when I was at the CIA so the government had no justification to withhold anything. Assange had no such access and will therefore be blind to the evidence that will be used against him.

Speaking of evidence, at no point during the trial did the government produce any proof of where or when I allegedly conveyed information about Operation Merlin to the reporter. The only fact established by the government beyond a reasonable doubt was the color of my skin and that I didn’t look like any of the CIA witnesses shuffled onto the stand.

Proving that I was black was enough for the EDVA, the jury, and the Espionage Act to find me guilty of offenses I did not commit. I was sentenced to 42 months in prison.

Hard To Believe I Survived Prison

As time has passed, I continue to try and pick up the shattered pieces of my life, the realization that I was fighting a battle impossible to win strikes me like a bolt of lightning. Neither justice, law, nor the truth stood a chance in my trial, and that leads me to believe none of those hollow tenets of American jurisprudence will matter in Assange’s case

Assange has none of the protections under the U.S. Constitution that I supposedly had, and he is continually brandished as an enemy aligned against America.

In my view, having been where Assange could be headed, the U.S. has already found him guilty. The only question is how long will the U.S. put him in prison.

I still find it hard to believe that I survived my time in prison, and I am rather certain Assange will not survive if sentenced to prison.

While I was in one of the U.S. prisons that the Crown Prosecution Service has repeatedly described as accommodating and attentive, I suffered a cardiac-related medical episode at Federal Correctional Institution Englewood in Colorado that would have been treated urgently if I was not incarcerated.

Instead of providing basic medical care, the prison administration and medical staff were dismissive, blaming me for my condition and refused to provide care. It was only through the effort of my wife, thousands of people who barraged the prison and warden with messages, and the eventual involvement of a U.S. Senator that I received the necessary care.

If those efforts on my behalf had not taken place, I would not have survived. The care available to Assange will be as abysmal if not worse than what I experienced.

Furthermore, at the onset of my prosecution, the government tried to force reporters to divulge their sources.

Whether there was any such thing as reporter/source protection was a gray area prior to my case. The government had no clear intent to pursue those who received classified information. No presidential administration had taken the direct step of charging a reporter with receiving classified information. But the question was once and for all decided by the EDVA in a government appeal during my case.

In keeping with its staunch defense of the U.S. government, the EDVA determined that there were no such protections for reporters or their sources when it came to criminal prosecutions, especially under the Espionage Act.

That victory for prosecutors under President Barack Obama’s administration set the terrible precedent that the U.S. government could not only use the Espionage Act to prosecute whistleblowers but also use the same law to go after those who receive and publish classified information.

We Share The Bravery To Stand Up To Abuses Of Power

Despite the attestations by the Crown Prosecution Service and U.S. prosecutors that Assange’s case is similar to mine—and others who have been prosecuted and persecuted under the Espionage Act, these similarities are manufactured to support the case for extradition.

The case against Assange by the U.S. is new and previously uncharted territory. The U.S. government has not previously prosecuted a reporter under these circumstances.

The only thing that I share with Assange is that neither of us has violated any U.S. law, including the Espionage Act, but we have both been victimized by a vengeful U.S. government. We share the bravery to stand up against government wrongdoing and abuses of power.

I blew the whistle against discrimination at the CIA because it went against all the ideals and values I was taught to hold dear as an American. I blew the whistle against a faulty and dangerous CIA program because doing so was in furtherance of the ideals and values that I believed and held dear. Assange published details of torture, war crimes, and diplomatic misconduct that represented a disregard for these same ideals and values.

In that sense, there are similarities between Assange and me. But overall the assertions of similarity by the prosecution are false invective to support an extradition.

I also find it very troubling that major media outlets in my country have largely ignored the extradition proceedings. I believe they are suffering from a false sense of security that based on their position and entrenchment with the powers that be they are somehow immune from prosecution under the Espionage Act.

Perhaps the U.S. media feels it is different from Assange and under no such threat. I remind them that notions of source/journalist protection were eliminated through my case.

The Assange case is a clear example of the government’s willingness to target journalists and media outlets throughout the world, which is why numerous press freedom organizations oppose the prosecution.

I sincerely hope other countries in the world are paying attention to the extradition proceedings in the U.K. What happens may unfold in any country in the world if the U.S. is not prevented from using the Espionage Act to quash dissent and punish those who have dared to take a stand against its contemptible and reckless conduct.

And if there is anything of meaning I can do for the rest of my life, it will be to shine the light of truth on how my country is wrongly using the Espionage Act out of a perverse sense of vengeance to silence and quash dissent.

*Kevin Gosztola edited and contributed a bit of reporting.

Comments ()