Film Review: 'Seized' Is A Love Letter To Community Journalism

The film examines the raids against the Marion County Record within the larger context of the decline of local newspapers.

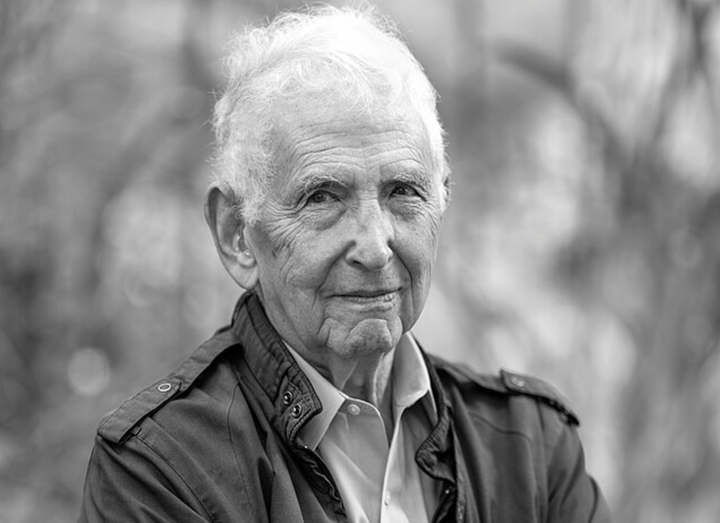

Most American journalists probably remember the raids against the Marion, Kansas, newspaper that is the focus of “Seized.” It was August 11, 2023, and local police showed up to the Marion County Record’s office and the home of its editor Eric Meyer. They took computers out of the newsroom as well as cellphones that belonged to Meyer and a few other reporters.

The police also took a computer and router from Eric’s 98-year-old mother Joan Meyer, who lived with her son and owned the newspaper with him. She accused the police of engaging in “Nazi stuff” and said if they caused her to have another stroke it would “murder” her. A day after, Joan died, and the trauma from the raid significantly contributed to her death.

In the aftermath, Marion police claimed that they had signed search warrants from magistrate judge Laura Viar, and that they were just investigating identity theft and the misuse of a computer. But during the months that followed, it became increasingly clear that the raids was retaliation against Eric and the Marion County Record, and the magistrate judge should have never authorized the raids.

“Seized,” which is directed by Sharon Liese and premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, explores the events that led up to the raid and the fallout that ensued. The film places the raids in the larger context of decline of local newspapers and how there is a vocal faction of Marion residents, who are hostile toward the Record. It also functions as a warm tribute to Joan and the respect that she garnered through her 50 years of work at the Record.

Liese is up front about the fact that this not a “typical story” that she would tell. However, when she heard about the incident on NPR, she drove to Marion to meet Eric. He told Liese that she was first and “got the scoop,” and that was the start of the project.

After a montage that frames the narrative, the film opens with Finn Hartnett, an intern from New York who worked for the Record for a year. Hartnett is Liese’s way of incorporating an outsider perspective. He’s immediately dropped head first into the town’s politics. “Things seem really tense between the paper and the mayor,” Hartnett says. As Eric tells Hartnett, “They don’t like when we ask questions.”

The current mayor of Marion is Mike Powers, who was elected in an unopposed race after the raids. He is part of the faction of residents that remain upset that negative press surrounding the raids introduced much of the world to this rural town of 1,900 people. Powers appears throughout the film to chastise Eric for acting as if he is some “champion of the free press” on the front lines of the First Amendment.

Liese obtained access to nearly everyone who played some role in the timeline that led up to the incident. Restaurant owner Kari Newell had Marion police chief Gideon Cody kick Eric and Record reporter Phyllis Zorn out of a meet-and-greet with Republican Congressman Jake LaTurner.

Later, the newspaper received public driving records for Newell that showed she had been caught drunk driving and later drove without a driver’s license. Newell had applied for a liquor license for her restaurant, and this information raised questions about the enforcement of the law. Eric shared the information with the police, and then soon after, officers conducted the raids.

The newspaper had operated in the town since about 1871. But rather than uniting around the Record as an institution that must be defended, it is treated by the mayor and other local officials like it is run by a bunch of outside agitators.

As Hartnett observes, there are a lot of people who say the Record is “too nosy,” and, “You’re too negative. Get out of our business.” This attitude feels like the result of decades of right-wing propaganda from Rupert Murdoch to Steve Bannon that has delegitimized the role of journalists in pursuing accountability and preserving democracy.

Liese offers a few examples that may illustrate why there is a vocal faction fed up with Eric and the newspaper. She points to an op-ed from Eric on the loss of education during the COVID-19 pandemic. He referred to kids’ letters to Santa to advance his argument. People were also apparently upset that the newspaper reported on the owner of a day spa in Marion, who shared risqué photos to a public website. A fired city administrator showed one of the photos to a city treasurer and was accused of sexual harassment.

Neither of these examples seem significant enough to generate the negative attitude emphasized in the film. Clearly, the mayor and other officials have fueled resentment toward the newspaper because they cannot tolerate reporters prying into their affairs and that has filtered down to parts of the community that associate or identify with the town’s leadership.

It is illuminating how Hartnett and Eric have differing perspectives on journalism. Hartnett learned journalism on the staff of the University of Chicago’s newspaper while Eric has a wealth of experience from working for local newspapers in the Midwest, like the Milwaukee Journal and the Daily Pantagraph. Hartnett is bothered by public relations and the fact that the town wants them to move on from the raids. He sometimes agrees with the vocal faction that says what the newspaper does is “intrusive.”

On the other hand, Eric understands what has been lost in the United States. "We used to have more aggressive journalism in this country. We used to have more newspapers that were checking things out. And as the newspaper industry has declined, instead of newspaper editors and publishers that care about their communities, we have great huge corporations” that do not really care whether rural American towns have access to news from their community.

I share Eric’s commitment to "aggressive journalism," and his worries about the future of small town newspapers like the Marion County Record. As I watched the film, I thought a lot about the experiences that I have gone through in my first year publishing a newsletter that covers the west Chicago suburb of Elmwood Park where I live. I have had to deal with a vocal faction that thinks the newsletter exists to disrupt the community.

Overall, “Seized” is primarily a love letter to small town newspapers. It only spends a few minutes making the point that the First Amendment is in jeopardy in countless American towns, and Marion was just a flashpoint in a wider struggle for freedom of the press.

But I do not believe that diminishes the film. There is immense value in telling stories that show the trials and tribulations of the press, especially in areas outside of urban centers like New York or Washington, D.C., that shape too much of our collective understanding of journalism.

"Seized" is screening at film festivals throughout 2026 and still seeking a distributor. Stay tuned for details on how to watch the film at home.

Subscribe to "The Weekly Matinee" for more film writing from Kevin Gosztola.

Comments ()