Listen To The Third Episode of 'Primary Sources' With Carey Shenkman (Exclusive For Paid Subscribers)

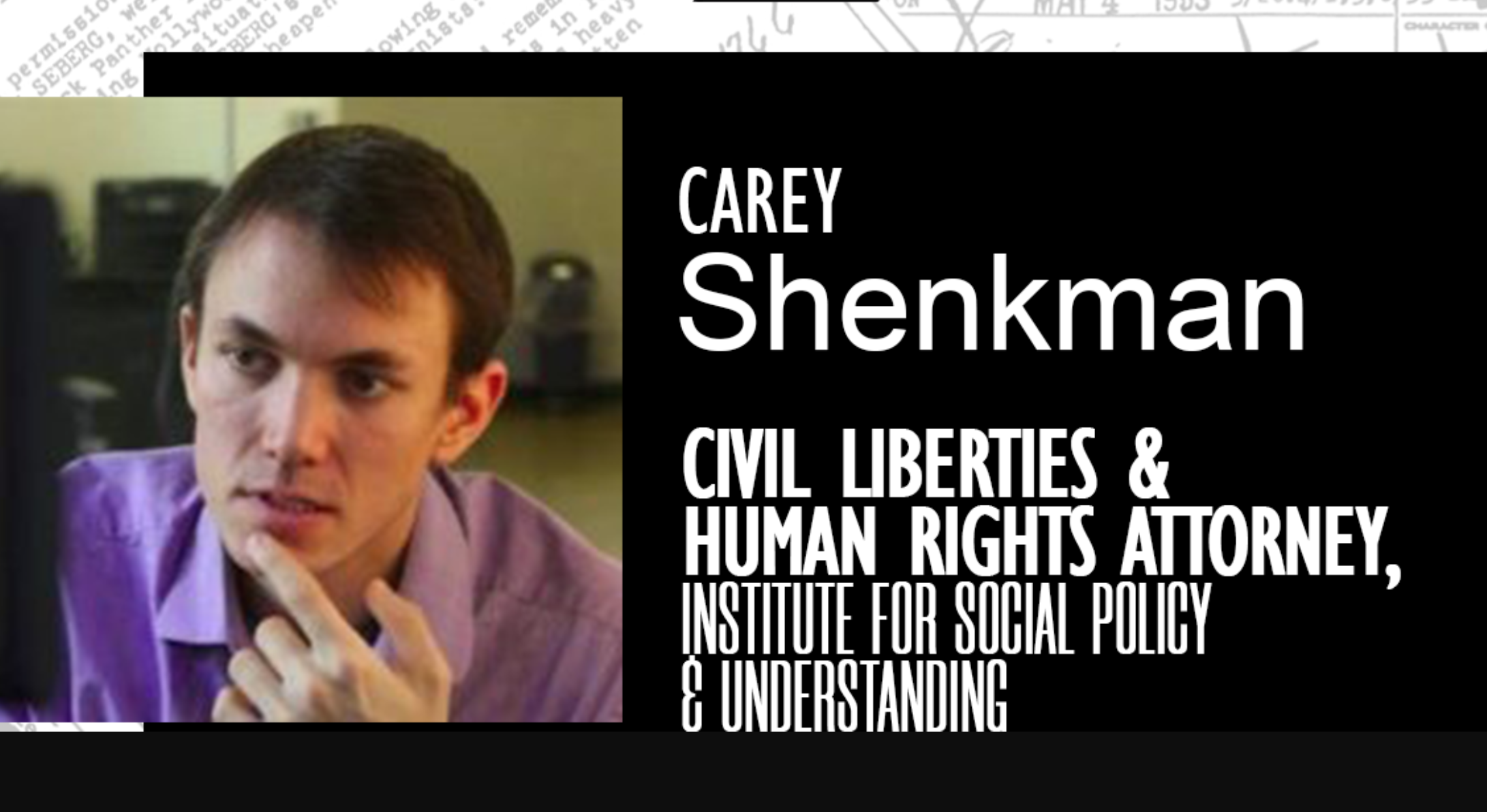

In the third episode of the “Primary Sources” podcast, human rights attorney Carey Shenkman joins host Chip Gibbons for a deep dive into the legal history of the United States Espionage Act.

Shenkman gave testimony on the 1917 law during WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s extradition trial. He is the co-author of the forthcoming book, A Century of Suppression: The Espionage Act from WWI to the War on Terror.

“Primary Sources” is essential listening for subscribers of The Dissenter, as it explores the stories of whistleblowers and truth-tellers, who “expose civil liberties and human rights abuses committed under the guise of national security and the challenges they face.”

It is a project of Defending Rights and Dissent, which champions the right to freedom of political expression and closely monitors how police and intelligence agencies in the United States engage in repression of activists, movements, and other individuals or groups.

Listen to the episode featuring Carey Shenkman, human rights attorney:

“The Espionage Act of 1917 is probably one of the most important yet least understood laws that impact freedom of expression in the United States,” Shenkman declares. “Most folks when you say the Espionage Act would assume that it applies to espionage or clandestine spying on behalf of foreign powers.”

But as Shenkman points out the law criminalizes conduct that goes well beyond espionage as it is understood, which has been the case since the Espionage Act was passed during World War I.

World War I was a politically repressive period. There was vibrant resistance to U.S. participation in the war, which was considered a European or foreign war until President Woodrow Wilson changed course.

“As part of that,” Shenkman recounts, “there was a very strict crackdown on anything that was considered dissent or disagreement with that involvement in the war effort.”

The Espionage Act became the principal tool of what Wilson dubbed his administration’s “firm hand of stern repression” against opposition to U.S. participation in the war. He had a zero tolerance policy for those who “injected the poison of disloyalty” into the most critical affairs. And he believed by dissenting citizens had sacrificed their civil liberties.

According to Shenkman, the law criminalized “libel” and that was the main means of repressing dissent. The first 2,500 prosecutions under the Espionage Act were on account of political speech and opposition to the war.

Eugene Debs, who was a Socialist presidential candidate, is one of the more famous Espionage Act prosecutions in the early history of the law. It also is an early example of “covert political surveillance.”

“His speech was transcribed in real time by federal investigators, and there was debate over whether he should be criminally charged under the Espionage Act for inciting disloyalty.” And Debs' trial became one that put the injustices of World War 1 on trial.

Throughout World War I and World War II, there was a thread tying J. Edgar Hoover’s reign as the head of the FBI to the Espionage Act. The law was deployed for prosecutions against the Black press. Hoover’s racism and xenophobia pushed him to label numerous Black publications as communist media. He believed communists were exploiting Black communities.

Shenkman goes into the cases brought against the Chicago Tribune and Amerasia, a small foreign affairs journal, and the trend toward applying the Espionage Act to the release of state secrets at the end of World War II.

In 1945, Amerasia was targeted by President Harry Truman’s administration after it published an analysis critical of post-war policies toward China that relied on “government sources who were deeply concerned.” Three journalists and three government source were arrested and pursued for allegedly conspiring to violate the Espionage Act.

Shenkman notes the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA, authorized a warrantless break-in into Amerasia’s offices and found secret documents. Journalists had their phones tapped and targeted their sources. It was claimed by the U.S. government that a “spy ring” was busted, but government misconduct and the lack of evidence of any espionage led to a collapse of the case.

Another historic example of repression highlighted involves Beacon Press and the Pentagon Papers. Beacon Press was a “publishing arm of the Unitarian Universalist Association.” Senator Mike Gravel read the Pentagon Papers from Daniel Ellsberg into the public record, and afterward, he sought a publisher to make the primary documents that made up the Pentagon Papers available to citizens.

President Richard Nixon’s administration caught wind of Beacon Press’ plans, but they lacked the money and resources for this project. Nixon intimidated the publisher. FBI agents visited the organization. Bank records for the religious organization were subpoenaed.

“It’s a really significant part of the Pentagon Papers episode because you have what was a smaller independent press that tried to publish the Pentagon Papers, and there was a serious Espionage Act investigation of them,” Shenkman concludes.

Comments ()