Listen To The Second Episode of 'Primary Sources' With James Goodale (Exclusive For Paid Subscribers)

The fiftieth anniversary of the United States Supreme Court overturning a ban on the publication of the Pentagon Papers was on June 30.

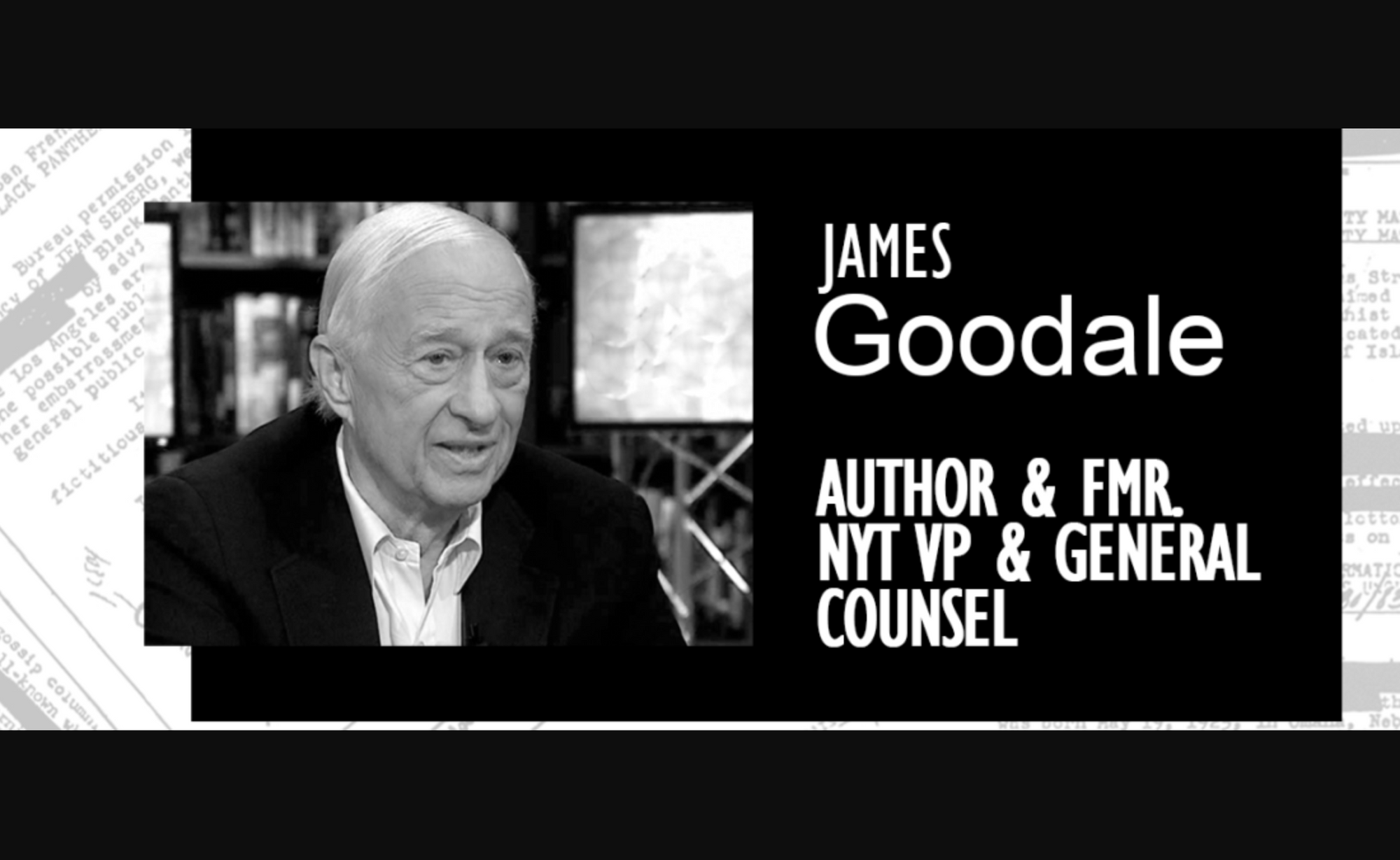

To mark the event, James Goodale, former general counsel of the New York Times, was interviewed by Chip Gibbons for the second episode of a new podcast series called “Primary Sources.” Goodale was part of the legal team that achieved this major First Amendment victory.

Gibbons is the policy director for Defending Rights and Dissent, which champions the right to freedom of political expression and closely monitors how police and intelligence agencies in the United States engage in repression of activists, movements, and other individuals or groups.

“Primary Sources” is essential listening for subscribers of The Dissenter, as it explores the stories of whistleblowers and truth-tellers, who “expose civil liberties and human rights abuses committed under the guise of national security and the challenges they face.”

Listen to the episode featuring James Goodale, former general counsel for the New York Times:

Goodale was involved in two significant press freedom battles before the Pentagon Papers. They resulted in crucial decisions that affirmed the First Amendment and showed it was a "hidden weapon" for protecting journalism.

The first case won was New York Times v. Sullivan in 1964, involving libel law, and the second case involved a reporter's right to their sources when it came to subpoenas.

In March 1971, as Goodale recalls, he learned at a "large social event" in Washington, D.C., that the Times received classified information.

"I was not told what it was, what it involved, or indeed what I was supposed to do. I took the hint, however, that I was supposed to know something about how that worked legally, even though I didn’t know the Pentagon Papers as such were the subject of the inquiry. So off I went looking up classified information laws."

Goodale learned six weeks later that information involved a classified version of the history of the U.S. relationship with Vietnam, and to judge whether publication deserved a robust defense, Goodale had to read some of the documents.

"I was shocked at what I read at the deception and the lies that were in the Pentagon Papers history," Goodale declares.

There was a debate within the Times over whether to respect the classified stamp that was on the Pentagon Papers.

“Those who thought the classified stamp should be respected were those who ordinarily would respect the authoritarian approach to the relationship between the government and the citizen," according to Goodale. "And on the other side was myself who said, yeah, okay, the classified stamp is important but the First Amendment is important too."

Goodale effectively persuaded the Times that it was crucial to subject government requests of this nature to First Amendment tests.

After the case made its way through the courts, freedom of the press won. The Supreme Court overturned the Nixon administration's ban on publication.

Goodale contends, "The Supreme Court didn’t say you didn’t show me clear and present danger, government. The Supreme Court didn’t even use clear and present danger. It used a test that applied immediate danger to the nation or its people, [a] huge requirement for the government to meet to stop publication."

President Richard Nixon's administration was "highly antagonistic" toward the press. "The general atmosphere was not dissimilar to the way it was under Trump."

For example, a Black New York Times reporter named Earl Caldwell was subpoenaed to force testimony from him about the Black Panther Party.

Winning meant the Supreme Court, like Goodale says, told the U.S. government stopping publication was one of those acts the government could not do.

When it comes to press freedom, Goodale argues the current landscape is worse than under Nixon due to the record number of sources prosecuted under Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

New York Times reporter James Risen was subpoenaed during Obama's administration, and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was indicted on Espionage Act charges during Trump's administration.

"Such indictments did not exist before the Pentagon Papers case in 1971," Goodale states. "It’s a very bad practice. I’m absolutely convinced that it’s not anticipated or provided for by the Espionage Act."

"If Assange is convicted it will be a real mess because it will mean that the Supreme Court has decided that the Espionage Act applies to publication," Goodale adds. "It will mean that anytime anyone wants to publish information related to the national defense, particularly when such information has been classified, that such publisher will be running a risk of being indicted."

"It will mean that no one will want to publish such information, and so it will mean the government has gained greater control over its information, since no one will want to take a chance on going to jail."

Comments ()