Legislation In Congress Would Finally Close Major Loophole In Federal Whistleblower Protections

Bills proposed include access to the courts and jury trials for federal whistleblowers who endure retaliation

Legislation introduced in Congress would fill multiple gaps in federal whistleblower protections and finally grant access to courts and jury trials for review of their cases.

All private sector whistleblower laws since 2002 have included court access, yet when the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act (WPEA) moved through Congress in 2012, court access was removed before it was passed and signed into law by President Barack Obama.

"The Make It Safe Coalition (MISC) Steering Committee praised the House Committee on Oversight and Reform (COR) leadership for combined legislation to finish what Congress started in the Whistleblower Protection Act of 2012," the coalition declared.

"Since that unanimously approved mandate, whistleblowers steadily have proven themselves indispensable against abuses of power that betray the public trust. Unfortunately, some of the most significant issues were postponed for further study eight years ago, without follow-up to add necessary teeth to the legislation."

As a result, the MISC Steering Committee argues free speech rights for whistleblowers in the United States have "fallen far behind the pace for global best practices protecting whistleblowers."

The Government Accountability Project, the Liberty Coalition, the National Security Counselors, the National Whistleblower Center, the Project on Government Oversight, Public Citizen, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, the Taxpayers Protection Alliance, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and Whistleblowers of America each engage in whistleblower advocacy and make up the steering committee.

Representative Carolyn Maloney, the chair of the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, introduced the Whistleblower Protection Improvement Act (WPIA). It grants federal employees, former federal employees, and applicants for employment, who seek "corrective action from the Merits System Protection Board [MSPB] based on an alleged prohibited personnel practice," access to courts and jury trials. [Note: Prohibited personnel practices are instances of retaliation.]

If no final order is issued by the MSPB within 180 days of submission, protected federal employees may notify the Office of the Special Counsel and the MSPB that they are filing a complaint for review by the appropriate U.S. district court. They would have the option to have the matter tried before a jury.

The MSPB, a quasi-judicial agency in the executive branch, is the only body that many federal whistleblowers can go to with their claims. However, it has an estimated backlog of nearly 3,000 complaints.

According to the National Whistleblower Center (NWC), the "MSPB has not had a quorum in over three years and has not had a single sitting member since May 2019."

"The MSPB’s political nature is a drawback for whistleblowers," the NWC further declares. "While the structure of the MSPB may be appropriate for handling the majority of its cases, which are simple civil service appeals that don’t raise political issues, it is not well equipped to handle whistleblower cases that can easily become politicized."

"Two of the three Board members must be of the President’s own political party, and one of the three Board members must be of the opposing political party. With only three members in total, this is particularly fraught. Additionally, because the Board members are political appointees, there is a constant risk of a lack of any or sufficient appointees, in a particularly politically-polarized environment."

John Kostyack, the executive director of the NWC, told The Dissenter, "We've had court access since the early 1990s for victims of discrimination, whether it is race, gender, or age. We think it's a long overdue catchup for a very important class of victims of retaliation.”

The House of Representatives has passed legislation that granted federal whistleblowers court access or judicial review at least three times.

Kostyack said the first time was in the 1990s. But the Senate has refused to pass legislation that grants federal whistleblowers access to the courts.

"I do think there are probably people in the federal government who don't want to lose their prerogative and control over the issue in the executive branch, and then you hear some people claiming it's going to gum up the courts," Kostyack added.

The NWC submitted a report to Congress that documented how this concern was overblown. Anti-discrimination laws granted federal employees access to courts, and Kostyack noted there was no sudden "flood of cases."

Additionally, Senator Dianne Feinstein introduced the Congressional Whistleblower Protection Act to ensure "all federal employees, contractors, and applicants can file an administrative complaint if their right to share information with Congress has been 'interfered with or denied.'"

The legislation would permit whistleblowers to go to a federal court with their complaint if a "favorable decision" was not received "within 210 days of filing" an "administrative" complaint.

Provisions would also guarantee a jury trial and that federal whistleblowers could try to recoup "lost wage and benefits," as well as reinstatement to their position in government.

For too long, federal whistleblowers have had to depend on the MSPB to check abuses that stem from the deep-seated contempt toward whistleblowers in many U.S. agencies.

An MSPB study highlighted by the NWC found that federal employee “perceptions of reprisal for disclosing wrongdoing nearly doubled between 2010 and 2016."

"Nearly half of the respondents to the MSPB federal workforce study in 2016 (or 46 percent) reported that they had observed one or more prohibited personnel practices."

Without access to courts, protection for whistleblowers will remain stronger in the private sector.

"Private sector protections are stronger, which is really insane considering that we need federal whistleblowers to expose waste, fraud, and abuse in the federal government, and particularly at a time when trillions of dollars are flowing as part of the COVID relief packages," Kostyack said. "New rules and rulemaking, including some that are rolling back regulatory actions, are flying fast and furious. We're losing checks and balances at the same time that we are getting vastly increased spending."

As the Make It Safe Coalition outlined, "Whistleblowers have long provided necessary oversight and accountability in our government. Unfortunately, executive branch leaders from President Roosevelt to President Trump have violated their workforce’s free speech rights, restricting Congress’ oversight capabilities."

There was a clear opportunity to ensure full protection back in 2009. Yet, according to the NWC, the Senate would not support stronger legislation and the Obama administration “retreated from earlier pledges to support a strong federal employee whistleblower law, and instead explicitly stated in private meetings that they would oppose full court access and due process protections for national security employees.”

Many of these same issues are likely to surface when a Republican-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee marks up the legislation.

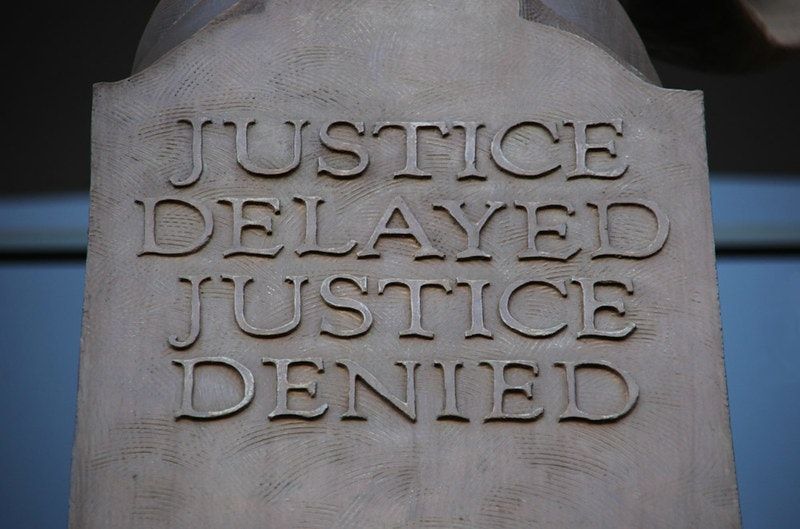

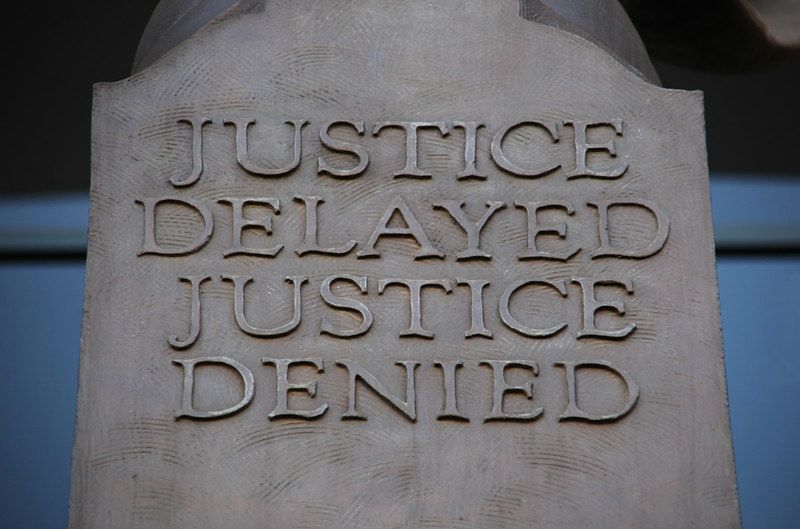

"Bottom line is right now these people are not getting justice. Everybody agrees they have these rights, but what's the point of having the rights if they can't be vindicated?" Kostyack concluded.

Comments ()