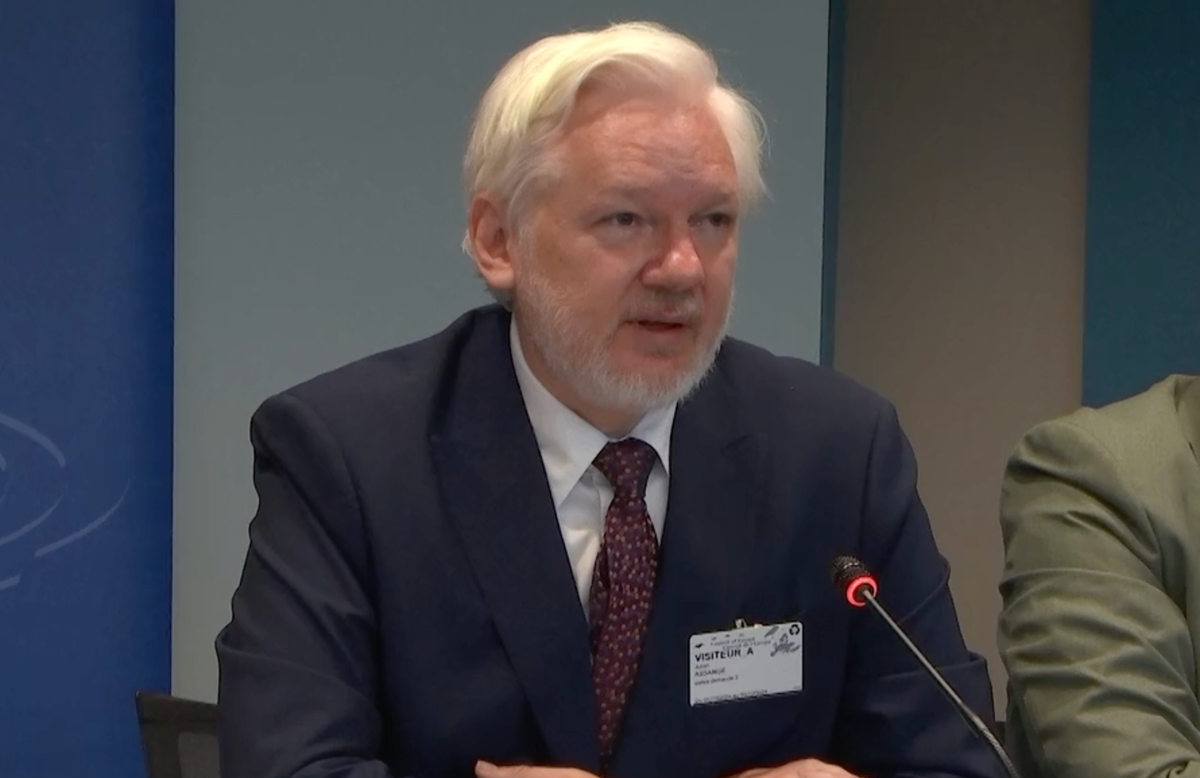

Julian Assange's Speech To The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

"The rights of journalists and publishers within the European space are seriously threatened. Transnational repression cannot become the norm here," Assange stated.

Below is a transcript of the prepared remarks that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange read before the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe's Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights. He testified as part of their inquiry into the United States government's political prosecution against him.

The transition from years of confinement in a maximum security prison to being here before the representatives of 46 nations and 700 million people is a profound and a surreal shift. The experience of isolation for years in a small cell is difficult to convey. It strips away one’s sense of self, leaving only the raw essence of existence.

I am yet not fully equipped to speak about what I have endured, the relentless struggle to stay alive physically and mentally, nor can I speak about the deaths by hanging, murder, and medical neglect of my fellow prisoners.

I apologize in advance if my words falter or if my presentation lacks the polish you might expect from such a distinguished forum. Isolation has taken its toll, which I am trying to unwind, and expressing myself in this setting is a challenge. However, the gravity of this occasion and the weight of the issues at hand compel me to set aside my reservations and speak to you directly.

I have traveled a long way, literally and figuratively, to be before you today. Before our discussion or answering any questions you might have, I wish to thank PACE for its 2020 resolution, which stated that my imprisonment set a dangerous precedent for journalists and noted that the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture called for my release.

I’m also grateful for PACE’s 2021 statement expressing concern over credible reports that U.S. officials discussed my assassination, again calling for my prompt release. And I commend the Legal Affairs and Human Rights Committee for commissioning a renowned rapporteur, Þórhildur Sunna Ævarsdóttir, to investigate the circumstances surrounding my detention and conviction and the consequent implications for human rights.

However, like so many of the efforts made in my case, whether they were from parliamentarians, presidents, prime ministers, the Pope, UN officials and diplomats, unions, legal and medical professionals, academics, activists, or citizens, none of them should have been necessary.

None of the statements, resolutions, reports, films, articles, events, fundraisers, protests, and letters over the last 14 years should have been necessary. But all of them were necessary because without them I never would have seen the light of day.

This unprecedented global effort because—of the legal protections that did exist—many existed only on paper; were not effective in any remotely reasonable time. I eventually chose freedom over unrealizable justice after being detained for years and facing a 175-year sentence with no effective remedy.

Justice for me is now precluded, as the U.S. government insisted in writing into its plea agreement that I cannot file a case at the European Court of Human Rights or even a Freedom of Information Act request over what it did to me as a result of its extradition request.

I want to be totally clear. I am not free today because the system worked.

I am free today after years of incarceration because I pled guilty to journalism. I pled guilty to seeking information from a source. I pled guilty to obtaining information from a source. And I pled guilty to informing the public what that information was. I did not plead guilty to anything else.

I hope my testimony can serve to highlight the weaknesses of the existing safeguards and to help those whose cases are less visible but are equally vulnerable. As I emerge from the dungeon at Belmarsh, the truth now seems less discernible. And I regret how much ground has been lost during that time period, how expressing the truth has been undermined, attacked, weakened, and diminished.

I see more impunity, more secrecy, more retaliation for telling the truth, and more self-censorship. It is hard not to draw a line from the U.S. government’s prosecution of me—its crossing the Rubicon by internationally criminalizing journalism to the chilled climate for freedom of expression that exists now.

When I founded WikiLeaks, it was driven by a simple dream: to educate people about how the world works so that through understanding we might bring about something better. Having a map of where we are lets us understand where we might go. Knowledge empowers us to hold power to account and to demand justice where there is one.

We obtained and published truth about tens of thousands of hidden casualties of war and other unseen horrors, about programs of assassination, rendition, torture, and mass surveillance. We revealed not just when and where these things happened, but frequently the policies, the agreements, and the structures behind them.

When we published “Collateral Murder” video, the infamous gun camera footage of a U.S. Apache helicopter crew eagerly blowing to pieces Iraqi journalists and their rescuers, the visual reality of modern warfare shocked the world. But we also used interest in this video to direct people to the classified policies for when the U.S. military could deploy lethal force in Iraq and how many civilians could be killed before gaining higher approval. In fact, 40 years of my potential 175-year sentence was for obtaining and releasing those policies.

The practical political vision I was left with after being immersed in the world’s dirty wars and secret operations was simple. Let us stop gagging, torturing, and killing each other for a change. Get these fundamentals right and other political, economic, and scientific processes will have space to take care of the rest.

WikiLeaks’ work was deeply rooted in the principles that this assembly stands for. Our journalism elevated freedom of information and the public’s right to know. It found its natural operational home in Europe. I lived in Paris, and we had formal corporate registrations in France and in Iceland. Our journalistic and technical staff was spread out through Europe. We published to the world from servers based in France, in Germany, and in Norway.

But 14 years ago the United States military arrested one of our alleged whistleblowers, Private First Class Manning, a U.S. intelligence analyst based in Iraq. The U.S. government concurrently launched an investigation against me and my colleagues. The U.S. government illicitly sent planes of agents to Iceland, paid bribes to an informant to steal our legal and journalistic work product, and without formal process, pressured banks and financial services to block our subscriptions and to freeze our accounts.

The U.K. government took part in some of this retribution. It admitted at the European Court of Human Rights that it had unlawfully spied on my U.K. lawyers during this time.

Ultimately, this harassment was legally groundless. President Obama’s Justice Department chose not to indict me, recognizing that no crime had been committed. The United States had never before prosecuted a publisher for publishing or obtaining government information. To do so would require a radical and ominous reinterpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

In January 2017, Obama also commuted the sentence of Manning, who had been convicted of being one of my sources.

However, in February 2017, the landscape changed dramatically. President Trump had been elected. He appointed two wolves in MAGA hats—Mike Pompeo, a Kansas congressman and former arms industry executive, and William Barr, a former CIA officer and U.S. attorney general.

By March 2017, WikiLeaks had exposed the CIA’s infiltration of French political parties, its spying on French and German leader, its spying on the European Central Bank, European economics ministries, and its standing orders to spy on French industry as a whole.

We revealed the CIA’s vast production of malware and viruses, its subversion of supply chains, its subversive of antivirus software, cars, smart TVs, and iPhones. CIA Director Pompeo launched a campaign of retribution.

It is now a matter of public record that under Pompeo’s explicit direction the CIA drew up plans to kidnap and to assassinate me within the Ecuador embassy in London and authorized going after my European colleagues, subjecting us to theft, hacking attacks, and the planting of false information.

My wife and my infant son were also targeted. A CIA asset was permanently assigned to track my wife and instructions were given to obtain DNA from my six-month-old son’s nappy. This is the testimony of more than 30 current and former U.S. intelligence officials speaking to the U.S. press, which has been additionally corroborated by records seized in a prosecution brought against some of the CIA agents involved.

The CIA’s targeting of myself, my family, and my associates through aggressive extrajudicial and extraterritorial means provides a rare insight into how powerful intelligence organizations engage in transnational repression. Such repressions are not unique. What is unique is that we know so much about this one due to numerous whistleblowers and judicial investigations in Spain.

This assembly is no stranger to extraterritorial abuses by the CIA. PACE’s groundbreaking report on CIA renditions in Europe exposed how the CIA operated secret detention centers and conducted unlawful renditions on European soil, violating human rights and international law.

In February this year, the alleged source of some of our CIA revelations, former CIA officer Joshua Schulte, was sentenced to 40 years in prisons under conditions of extreme isolation. His windows are blacked out, and a white noise machine plays 24 hours a day over his door so that he cannot even shout through it. These conditions are more severe than those found in Guantanamo Bay.

But transnational repression is also conducted by abusing legal processes. The lack of effective safeguards against this means that Europe is vulnerable to having its mutual legal assistance and extradition treaties hijacked by foreign powers to go after dissenting voices in Europe.

In Michael Pompeo’s memoirs, which I read in my prison cell, the former CIA director bragged about how he pressured the U.S. attorney general to bring an extradition case in response to our publications about the CIA.

Indeed, acceding to Pompeo’s requests, the U.S. attorney general re-opened the investigation against me that Obama had closed and re-arrested Manning this time as a witness. Manning was held in a prison for over year, fined $1000 a day in a formal attempt to coerce her into providing secret testimony against me. She ended up attempting to take her own life.

We usually think of attempts to force journalists to testify against their sources, but Manning was now a source being forced to testify against their journalist.

By December 2017, CIA director Pompeo had got his way, and the U.S. government issued a warrant to the U.K. for my extradition. The U.K. government kept the warrant secret from the public for two more years while it, the U.S. government, and the new president of Ecuador moved to shape the political, the legal, and the diplomatic grounds for my arrest.

When powerful nations feel entitled to target individuals beyond their borders, those individuals do not stand a chance unless there are strong safeguards in place and a state willing to enforce them. Without this, no individual has a hope of defending themselves against the vast resources that a state aggressor can deploy.

If the situation were not already bad enough, in my case the U.S. government asserted a dangerous new global legal position: only U.S. citizens have free speech rights. Europeans and other nationalities do not have free speech rights. But the U.S. claims its Espionage Act still applies to them, regardless of where they are.

So Europeans in Europe must obey U.S. secrecy law with no defenses at all as far as the U.S. government is concerned. An American in Paris can talk about what the US government is up to - perhaps. But for a Frenchman in Paris, to do so is a crime with no defense, and he may be extradited just like me.

Now that one foreign government has formally asserted that Europeans have no free speech rights, a dangerous precedent has been set. Other powerful states will inevitably follow suit.

The war in Ukraine has already seen the criminalization of journalists in Russia, but based on the precedent set in my extradition, there is nothing to stop Russia, or indeed any other state, from targeting European journalists, publishers, or even social media users by claiming that their domestic secrecy laws have been violated.

The rights of journalists and publishers within the European space are seriously threatened. Transnational repression cannot become the norm here. As one of the world's two great norm-setting institutions, PACE must act. The criminalization of newsgathering activities is a threat to investigative journalism everywhere.

I was formally convicted by a foreign power for asking for, receiving, and publishing truthful information about that power while I was in Europe. The fundamental issue is simple: Journalists should not be prosecuted for doing their jobs. Journalism is not a crime; it is a pillar of a free and informed society.

Mr. Chairman, distinguished delegates—if Europe is to have a future where the freedom to speak and the freedom to publish the truth are not privileges enjoyed by a few but rights guaranteed to all, then it must act so that what has happened in my case never happens to anyone else.

I wish to express my deepest gratitude to this assembly, to the conservatives, social democrats, liberals, leftists, greens, and independents, who have supported me throughout this ordeal, and to the countless individuals who have advocated tirelessly for my release. It is heartening to know that in a world often divided by ideology and interests there remains a shared commitment to the protection of essential human liberties.

Freedom of expression and all that flows from it is at a dark crossroad. I fear that unless institutions like PACE wake up to the gravity of the situation it will be too late.

Let us all commit to doing our part to ensure that the light of freedom never dims, that the pursuit of truth will live on, and that the voices of the many are not silenced by the interests of the few.

Comments ()