Incarcerated Journalist, Now At Texas Supermax Facility, Remains In Solitary

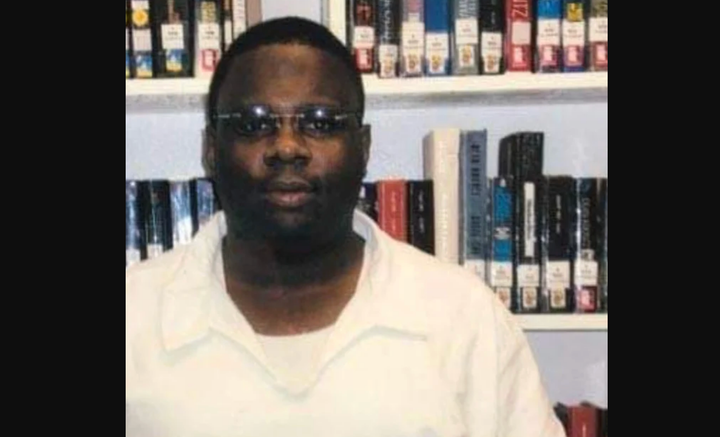

Incarcerated journalist Jeremy Busby says Texas state prison staff are inappropriately denying him access to members of the press and refusing to restore his phone privileges

Incarcerated journalist Jeremy Busby, who remains in solitary confinement conditions, says Texas state prison staff are inappropriately denying him access to members of the press and refusing to restore his phone privileges. He also says that staff has twice destroyed all of his personal property, including legal paperwork.

In early September 2024, The Dissenter published a report on what seemed like a glaring example of retaliation against a prisoner for writing about systemic problems in Texas state prisons.

Busby provided an update on January 6 that indicated he has twice been transferred to a new facility during the past six months. Each time, "personal property" and legal paperwork that he had in his possession were destroyed.

He was first transferred from the Jim Ferguson Unit north of Houston to the Alfred D. Hughes Unit in Gatesville. Then he was transferred from Hughes to the Estelle Supermax Penitentiary in Huntsville, where he currently is held.

At this Supermax facility, Busby told The Dissenter that he has a toilet that only flushes once every 30 minutes. His phone privileges still have not been restored, despite the fact that restrictions supposedly expired in July 2024.

Prison officials overturned the “bogus sexual assault case” that was used to justify his placement in solitary confinement, yet he still is subject to these harsh conditions. He claims that censorship of his mail and other forms of harassment continue.

Busby also mentioned that he is in need of “financial support” to replace his “personal property, including reference books used for writing.”

Despite the alleged harassment and restrictive confinement conditions, Busby is still writing articles. The following is an op-ed that Busby submitted to The Dissenter. It reflects on a recent visit to the prison's infirmary.

Texas Prison Introduces New ‘Behavioral Intervention Plan’: The Attack Dog

by Jeremy Busby

It started as a routine trip for a medical examination in the prison's infirmary but ended with disturbing images from the civil rights era.

When I entered the prison infirmary and stopped at the check-in desk to register with the officer, everything seemed normal until I noticed this huge dog sitting behind the desk giving me a deadly glare.

I had been incarcerated in a Texas prison for over 25 years and had been exposed to a number of different types of dogs, While they varied in breeds, they were all midsize canines trained to locate drugs or track the scent of an escapee. I had never encountered one of this magnitude in both size or intimidation. Strapped around its body was a Teflon vest that had the words, "Attack Dog Do Not Touch!"

"Attack dog?" I thought to myself, "What the hell was an attack dog doing inside the prison's infirmary?” Instead of asking questions as I descended deeper into the infirmary where the nurse's stations were, I decided to use practical logic to answer them. The canine most likely belonged to an outside law enforcement agency that was at the prison for whatever reason. Outside law enforcement agencies had visited numerous prisons facilities where I had been assigned, bringing along with them various law enforcement instruments. So it was feasible that they had decided to bring an attack dog this time.

A few hours later, a mentally ill prisoner had barricaded himself in his cell on my block. After numerous requests by the guard to exit the cell peacefully, reinforcement was called. Ranked guards in riot gear armed themselves with canisters of chemical agents. Then I saw another guard dressed in combat fatigues enter the door with the frightening attack dog from the infirmary trailing behind him on a leash.

Other prisoners had already been screaming to the ranking guards that the prisoner was mentally ill and should not be sprayed with chemicals. When the attack dog appeared, the shouts shifted to threats of collective protest. Prisoners demanded that the guards not release the attack dog on the barricaded prisoner.

Now, I was perplexed! Up until that point I had never heard of such a practice. I knew prison officials were looking for more humane ways to deescalate and solve conflicts like the one we were witnessing, but the introduction of an attack dog was beyond imaginable. Of course, we were in the state of Texas, but this was 2024, not 1954!

As the attack dog neared the mentally disturbed prisoner cell it became more agitated, as if its handler had given it a cue. It no longer trailed the guard, instead it forcibly led the guard having to be physically restrained. As it rise up in midair on its hind legs and let off it ferocious bark, my mind was bombarded with daunting images of the civil rights movement when law enforcement officer allowed dogs to violently attack protesting citizens.

The mentally ill prisoner exited the cell before the attack dog could be unleashed.

The next day I wanted to prove that the presence of an attack dog was a product of a rogue prison official at my facility. I went to the prison's law library to research policy. There was just no way that the prison leadership was aware of or sanctioned this antiquated and barbaric practice. To my surprise, I was wrong! In April 2024, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) Executive Director Bryan Collier had implemented a new “Behavioral Intervention Plan” that mandated the agency use of "Control Canines" or attack dogs.

According to the plan [PDF], control canines are trained to apprehend on command, sight, or in response to provocation—enhancing security measures to protect people or property.

Ironically, this controversial plan came just as the state's Sunset Commission Advisory Commission, a legislative appointed committee which examines the effectiveness of state agencies, reported that the prison agency failed to document the type of force its staff uses against prisoners, which "leads to errors that hinders the agency's ability to ensure safety to prisoners, staff and the general public."

"TDCJ too quickly defaults to a cultural inertia of doing things the way they have always been done," the report added.

With Texas prisons’ history of violating prisoners’ basic human rights and its lack of transparency, the last thing the troubled prison agency should have implemented was a policy that called for an attack dog. More productive alternatives would have been adding more trained behavioral intervention specialists and trained social workers to the staff of the state’s prisons.

Collier has publicly declared his objectives to change the prison's punitive culture to emphasize rehabilitation over punishment by 2030. However, his actions indicate a maintenance of the status quo or in the case of the attack dog, a turn toward dehumanizing practices closely associated with Jim Crow laws of the 1900s in the American South.

Taxpaying citizens of Texas deserve a leader who possesses a more ethical vision for the county's largest prison system. They should, along with the state's elected officials, implement a behavioral intervention plan for Collier and his deputies and eliminate the utilization of attack dogs against prisoners.

For more information on Jeremy Busby, visit Join Jeremy.

Comments ()