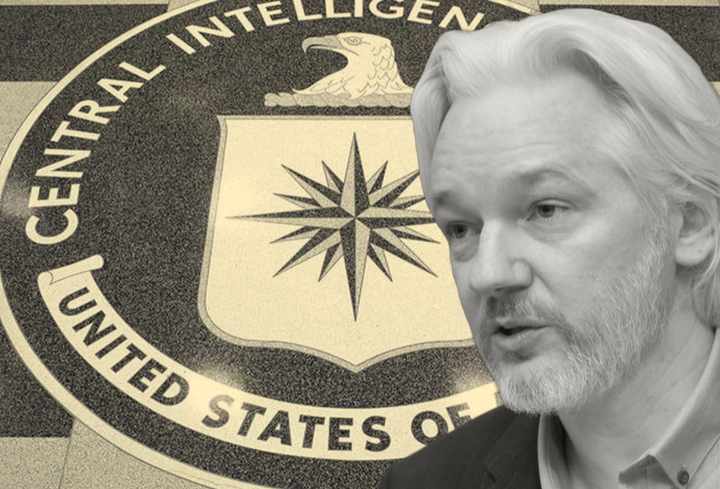

Imprisoning Drone Whistleblower In Isolation Unit May Jeopardize US Appeal In Assange Extradition Case

The Federal Bureau of Prisons put Daniel Hale in a Communications Management Unit, even though they know he lives with post-traumatic stress.

A few weeks before the United States government’s appeal hearing in WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s case, the Federal Bureau of Prisons imprisoned drone whistleblower Daniel Hale in a unit established for prisoners considered to be terrorists or “high-risk inmates.”

The move may undermine the Crown Prosecution Service’s ability to persuade the High Court of Justice in the United Kingdom that a lower court judge committed an error when Assange’s extradition was denied. Judge Vanessa Baraitser determined it would be “oppressive” to his mental health.

On March 31, Hale pled guilty to violating the Espionage Act when he released documents related to the Pentagon’s drone program to journalist and Intercept co-founder Jeremy Scahill. He was sentenced on July 27 to 45 months in prison.

Hale arrived at United States Penitentiary Marion in Illinois on October 6 and was placed in a “Communications Management Unit” (CMU), which was developed in the 2000s as part of the “war on terrorism.”

Assange faces similar charges under the Espionage Act for publishing documents that WikiLeaks obtained on U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, as well as U.S. foreign policy and the detention of prisoners at Guantánamo Bay.

In denying the extradition request, Baraitser did not cite any of the evidence from witnesses on CMUs, but testimony is available in the record for Assange’s legal team to reference when challenging prosecutors' “assurances” that Assange would be treated humanely if extradited.

The Testimony Of A Former USP Marion Warden

Maureen Baird was the warden of USP Marion from 2016 to 2017. She was responsible for overseeing the entire prison and “specifically familiar” with the CMU.

“CMUs are a separate prison within a prison, where almost every aspect of their prison life occurs within that housing unit,” Baird declared in her statement to the court. “At the Marion prison, a small outdoor recreation area is available to the inmates. However, it does not remotely offer the same exercise or recreational accommodations found at a regular prison facility.”

“There are tables set up in the outdoor recreation cages, where inmates can participate in board or card games. There is limited space for outdoor walking and short of walking in circles, or a short horizontal pattern, it is difficult for an inmate to engage in any meaningful and healthy outdoor exercise,” Baird added.

“All outside communication of these inmates must be live monitored by an FBI agent. All telephone calls need to be scheduled in advance and an agent must be available to listen and record any call with an inmate’s family members. This is not as easily accomplished as it appears.”

According to Baird, “Agents are not always available on certain days or at certain times, and the inmate’s counselor must also be available to coordinate any telephone calls. All incoming and outgoing mail is carefully scrutinized before delivery to the intended recipient.”

"Programs within CMUs are also very limited and do not offer the same opportunities as those afforded to inmates housed in the general population of the main section of the institution,” Baird noted.

“During my regular weekly rounds of the Marion CMU, I often had a barrage of complaints from these inmates pertaining to the absolute boredom they experienced and lack of meaningful programs in the unit.”

It is true that a prisoner may challenge their CMU placement through the BOP’s “Administrative Remedy Program.” However, as Baird described, it is “arduous and lengthy” and “often results in a denial of whatever remedy the inmate is requesting.”

“I would confidently state that it is unlikely any inmate has ever been successful in his appeal to be transferred out of the CMU,” Baird stated. “Inmates in the CMU receive biannual program reviews, which are informal, scheduled meetings where they meet with members of their unit team and discuss amongst other things, their continued placement in the CMU.”

“As warden, I would meet with the CMU unit team staff and discuss each case to determine if we believed there was a continued need for these types of restrictive measures. A recommendation was then forwarded from the Warden to the BOP’s Counter-Terrorism Unit and finally to the BOP’s Assistant Director of Correctional Programs, for a final decision.”

“During my assignment at USP Marion, I recall only one time, where I made a recommendation for an inmate to be transferred out of the CMU,” Baird shared. “But that recommendation was met with a denial. I do not recall any inmate ever being transferred out of the CMU, other than a transfer to the sister-CMU at the USP Terre Haute.”

CMUs May Cause 'Distress Leading To Significant Levels Of Depression'

Joel Sickler, the head of a criminal defense litigation support firm, testified as an expert on federal prisons and also included details related to the CMUs in his statement to the court.

“For any inmate, and many of my clients, the level of monitoring of their lives can—and often does—cause distress leading to significant levels of depression,” Sickler declared. “In my experience, those inmates who are placed in CMUs experience this exponentially.”

Hale regularly saw a court-appointed therapist before he was detained in April—because the therapist ratted him out to pretrial services.

Authorities decided Hale might try and harm himself, since he lives with post-traumatic stress from the moral injury of being involved in the drone program. In spite of his poor mental health, and what the CMU could do to make his health worse, the Bureau of Prisons still designated him for isolation, which they could do to Assange.

“The near complete lack of process means an inmate in a CMU is highly unlikely to leave it and has no idea for how long they will remain. This level of treatment is far more Reading Gaol, than a modern efficient prison system.” (A reference to the now-shuttered prison in Britain where poet and playwright Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for being a homosexual.)

Sickler asserted if Assange was put in a CMU it would be a “de facto sentence of solitary confinement.”

The government’s statements about the American prison system, according to Sickler, did not reflect reality.

Although a prisoner may challenge their placement, which is “regularly subject to review,” the “administrative process within the prison and the challenging process through the federal court system is exceedingly difficult.”

“Federal courts historically have given the BOP great latitude in their decision making and unless it can be established that the inmate is being held in conditions that are unconstitutional (i.e., cruel and unusual), they take a hands off approach,” Sickler added.

CMU's Visitation Policy Even More Restrictive Than The 'Supermax'

The appeal submitted on behalf of the U.S. does not address the evidence that was put on the record regarding CMUs. It, however, deals with special administrative measures (SAMs), which is another system for restrictive confinement that could be applied against Assange if authorized by the attorney general.

Included in the evidence on CMUs was a reference to the Center for Constitutional Rights’ (CCR) work challenging the due process violations that routinely occur to prisoners. They described it in 2010 as “an experiment in social isolation.”

That same year CCR filed a federal lawsuit against the BOP and officials involved in overseeing CMUs. They had oral argument before the D.C. Court of Appeals on October 18, where they urged the court to reverse a lower court’s decision and recognize the necessity of ending the trampling of human rights.

“Unlike others held in the federal prison system, people in CMUs are forbidden from any physical contact during visits with their children, spouses, family members, and other loved ones. They are not even allowed a brief embrace upon greeting or saying goodbye,” CCR detailed.

If Assange’s partner Stella Moris and his two children traveled from London to visit him in a CMU at Marion or Terre Haute, he would not be able to hug his children, Gabriel and Max. Assange’s children could not sit with Assange because they would likely be separated by a partition. (Note: In Belmarsh prison, where Assange is jailed, he may hold and interact with his kids so long as the COVID-19 pandemic remains contained.)

“While the BOP claims that these units were created to more effectively monitor communications, there is no security explanation for banning physical contact during visits, as visitors are comprehensively searched before visits and prisoners are strip searched before and after visits.”

“The ban on physical contact during visits contradicts the BOP's own policy recognizing the critical importance of visitation in rehabilitation and prison re-entry,” CCR argued. “The CMUs' visitation policy is even more restrictive than that of the BOP's notorious ‘supermax’ prison in Florence, Colorado, where some prisoners have over four times more time allotted for visits than prisoners in the CMU."

Baraitser was persuaded by the defense’s contention that Assange would be designated to the “supermax” known as ADX Florence, which is notorious for its condition and effect on mentally ill prisoners. She also found there was a “real risk” he would be subject to SAMs in a U.S. prison.

"The detention conditions in which Mr. Assange is likely to be held are relevant to Mr. Assange’s risk of suicide,” Baraitser stated.

As part of a desperate move to salvage the extradition case, prosecutors offered “assurances” in their appeal, which were not offered during the extradition hearing but are before the appeals court.

One of the “assurances” is that the United States will not impose SAMs on Assange before trial or after conviction if he is extradited, although they might if he commits any “future act that met the test” for imposing such measures. (The appeal does not specify what type of act would qualify him for harsher confinement.)

Importantly, the assurance leaves open the possibility that Assange would be designated for a CMU if convicted, a possibility that seems even more realistic since the Bureau of Prisons and the Justice Department went ahead and shipped someone convicted of violating the Espionage Act to a CMU.

After what was done with Hale, it is hard to see how the “assurances” could be considered adequate enough to erase the concerns Baraitser had about jailing or incarcerating Assange in the United States.

Placing Assange in a CMU would be “oppressive” to his mental health as well.

Comments ()