Espionage Act Case Against Chinese Student For Drone Photography Could Have First Amendment Implications

It also seems that Chinese student Fengyun Shi was only charged because of his nationality.

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers of The Dissenter. Become a subscriber with this special offer and support independent journalism on press freedom.

The United States government charged a Chinese student named Fengyun Shi with six Espionage Act misdemeanors. He allegedly photographed U.S. naval vessels with an unregistered drone.

Although Shi was not engaged in newsgathering, if convicted, this rare case may have implications for the First Amendment. It also seems that Shi was only charged because of his nationality.

On January 6, 2024, Fengyun Shi, a “foreign student visa” holder, was nearby Huntington Ingalls Industries headquarters in Newport News, Virginia. He lost control of the aircraft, and it “became stuck in a local residence’s tree,” according to an affidavit by FBI Special Agent Sara Shalowitz [PDF].

An unnamed resident contacted Newport News police after Shi allegedly confirmed that he was operating the drone near the Newport News Shipyard and that he “was a Chinese National.”

Shi was wearing a University of Minnesota sweatshirt and indicated that he was a “student on break vacationing in the area.” Yet the resident possibly believed that Shi could be a Chinese spy because they photographed Shi, Shi’s ID, and the license plate of Shi’s Tesla rental car.

Police responded and spoke with Shi, who naturally informed him that he was trying to retrieve his drone. The police allegedly “asked why Shi was flying the drone in that area” and told him “that the weather was too dangerous to fly a drone.”

At this point, the affidavit states that Shi was “very nervous.” He apparently did not know that he was flying the drone in “restricted air space.”

“Shi presented what appeared to be an iPhone, connected to the drone, and said he thought he could fly the drone in the residential area,” according to Shalowitz’s version of the incident. “Shi became nervous and cradled the cellphone toward his body and stated he just needed help getting it out of the tree.”

The affidavit also claims a “source” at Huntington Ingalls Industries contacted the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) on January 6 to report that Shi was flying a drone near the U.S. military contractor’s entrance.

Police did not remove the drone from the tree. The wind knocked it to the ground a day later, and police returned. It eventually wound up in the possession of NCIS before the FBI seized it and the SD card containing photos and videos, which appeared to "capture U.S. Naval vessels and/or vessels intended for use by the U.S. Navy.”

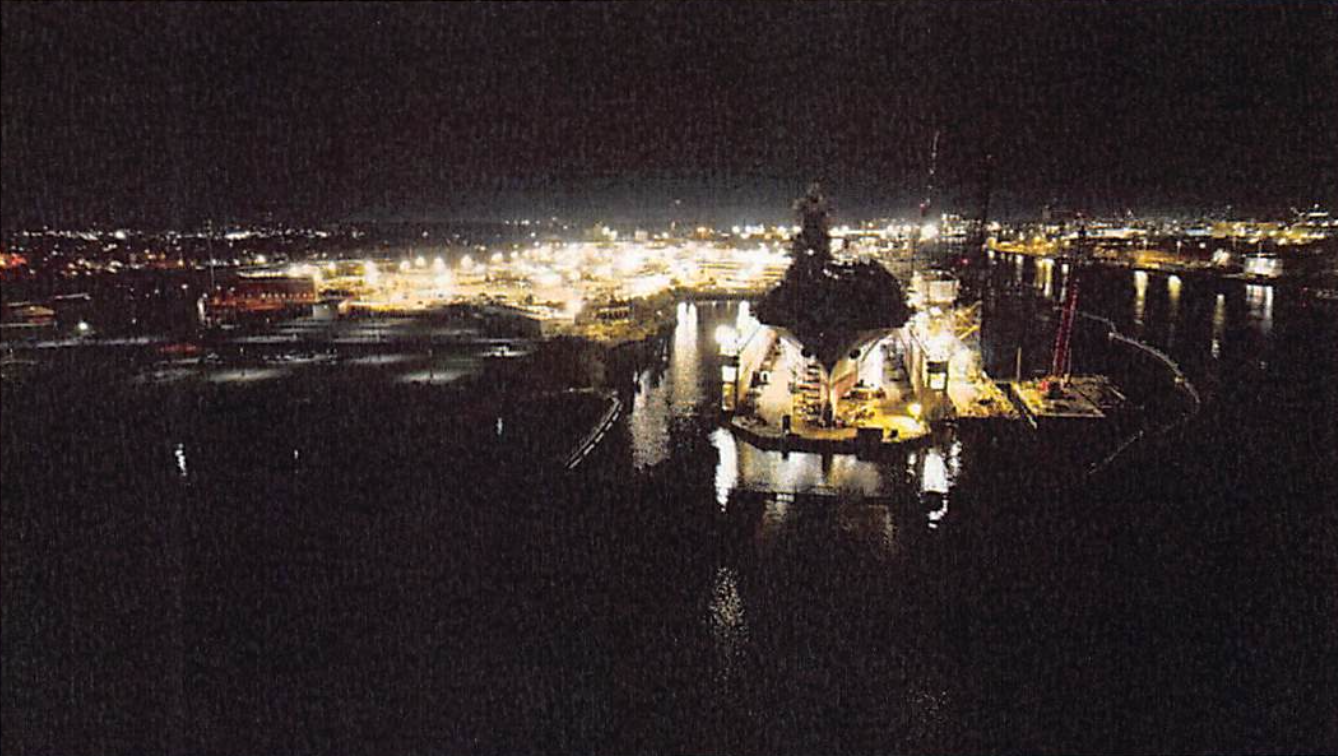

The affidavit included two night photos of a BAE Systems shipbuilding facility and one photo of the Newport News Shipbuilding (NNSB) facility. (NNSB is a subsidiary of Huntington Ingalls.)

Shi was conditionally released while awaiting trial. A bench trial is set for June 20. Two interpreters who speak Mandarin are assigned to the case as well.

On January 18, Shi was initially charged with six felonies in the Eastern District of Virginia. But on February 1, U.S. prosecutors lowered the charges to misdemeanors.

It is unclear what led prosecutors to shift course, however, the FBI affidavit contains no evidence or suggestion that Shi was engaged in espionage on behalf of the Chinese government. (The Dissenter tried to access the superseding "criminal information" in the unsealed docket, which could provide important context, but it is unavailable.)

The FBI affidavit supporting charges emphasizes the extent to which Shi was nervous, like that is evidence of guilt, but it is just as possible that Shi was nervous because English is a second language, which he does not speak well. (Add U.S. police into the mix, and trying to communicate was probably even more stressful.)

PetaPixel, a photography news site, highlighted Shi’s case and noted that the outcome may limit “a person’s right to photograph on public land.”

The site spoke to Emily Berman, a professor at the University of Houston who teaches national security law, who confirmed that the law had never addressed what Shi allegedly did to “any significant degree.” She added, “There’s definitely no reported cases.”

According to PetaPixel, the "presiding judge" found “only one reported case in precedent.”

“The Justice Department has guidelines that say [nationality] is not supposed to play a role in a criminal investigation, but there are exceptions to that rule for national security and border-related investigations,” Berman further contended. “It certainly seems likely that the fact Shi is a Chinese national raises red flags for investigators that wouldn’t necessarily go up in the same way if he was an American citizen, rightly or wrongly.”

A little more than ten years ago, a photographer and reporter with the Toledo Blade took photos of the Joint Systems Manufacturing Center, a tank manufacturing plant in Lima, Ohio. They were harassed and detained by U.S. military police, and police seized their cameras and memory cards.

When the confiscated property was finally returned, the military police had destroyed all photos of the tank manufacturing plant, as well as photos of a nearby oil refinery. The Blade sued the U.S. government for violating the First Amendment Privacy Protection Act, which is supposed to prevent the search or seizure of “any work product materials possessed by a journalist.”

The lawsuit resulted in an $18,000 settlement, but the U.S. government admitted no wrongdoing.

An Army public affairs officer’s statement strongly suggested that military police were enforcing the Espionage Act provision for military installations that Shi is accused of violating.

Cindy Gierhart, who was a legal fellow for Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said at the time that the statute is “overly broad because it doesn’t distinguish military secrets and what is plainly visible to the public.”

“[M]aking it a crime to photograph the outside of a building that is plainly marked as a government facility, is viewable to any passerby or on Google Street View, and doesn’t betray any military secrets doesn’t serve any purpose,” Gierhart added.

The same may be said in Shi’s case. What did Shi photograph or video with his drone that isn’t available via Google Street View or viewable to the public as they pass by?

Prosecutors do not allege that Shi infiltrated the area and photographed or recorded classified components of U.S. naval aircraft carriers or nuclear submarines, which Huntington Ingalls also manufactures. Shi is not accused of launching a spy balloon. They simply accuse Shi of flying an unregistered drone over the buildings for two U.S. military contractors.

Given that this type of case is historically rare, those who value the First Amendment should worry about how Shi's case may negatively affect the right to engage in photography and journalism in the United States. The outcome—and the national security state paranoia underpinning the charges—will likely add to excessive restrictions that have existed for more than a decade.

Comments ()