'Cover-Up': The Complicity Of The Press In US Violence

All governments lie. Seymour Hersh built his journalism career around the creed that it’s a reporter’s job to expose government lies, especially those told by the United States government.

Hersh unraveled a number of major cover-ups and earned a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the My Lai massacre in Vietnam. And yet, despite repeated lawless and violent acts throughout history, prestige media organizations remain reluctant to encourage journalism that questions the U.S. military and broader security state. Most editors and producers shun reporters, who dare to follow in Hersh’s footsteps.

“Cover-Up,” directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, takes Hersh’s work over the last half century and examines what Poitras describes as the “long history of cycles of impunity, of mass atrocities that are committed and nobody is held accountable.”

Its importance has only increased with the U.S. military’s attack on Venezuela and the CIA kidnapping of President Nicolas Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. In fact, the New York Times and the Washington Post reportedly knew about the operation before it took place and declined to expose it. Eighty people in Venezuela died.

The film opens with a cover-up that few people may attribute to Hersh: the Dugway incident, where the U.S. Army lied about chemical weapons testing that killed 6000 sheep. The sequence is composed of declassified footage and archival interviews, including a clip of a much younger Hersh, who refuses to back down when challenged.

A third of the documentary focuses on the My Lai massacre with Hersh recounting how he came to learn about the atrocity. The U.S. military portrayed the incident as the result of one “bad apple.” Hersh further documented the “kill anything that moves” policy in Vietnam and demonstrated that William Calley was a scapegoat. Still, U.S. Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland retired and never faced prosecution for war crimes.

Another significant portion of the film recounts Hersh’s work for the New York Times in the 1970s. Right after he was hired, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wanted to speak with Hersh. He was afraid of the reporter who had uncovered the My Lai massacre.

Kissinger's fear was valid. Hersh spoke to sources, who described the secretary's role in economic warfare against Salvador Allende’s government in Chile. He also learned about a document called the “Family Jewels” which detailed “every criminal act” that violated American laws—foreign assassinations, domestic spying, and even mind control. This reporting sent the CIA into a meltdown and triggered the Church Committee investigation.

A Through Line From Vietnam To Iraq To Gaza

The film is at its best when Poitras and Obenhaus prod Hersh to be honest and go where he does not want to go. Like when he says, “You’re getting me to think about things that I don’t want to think about,” as he revisits his reporting on the Vietnam War and how the U.S. military took young men and turned them into murderers. Or when he says, “I was very happy not talking about myself” and thinks he’s shared too much about what he’s done as a reporter.

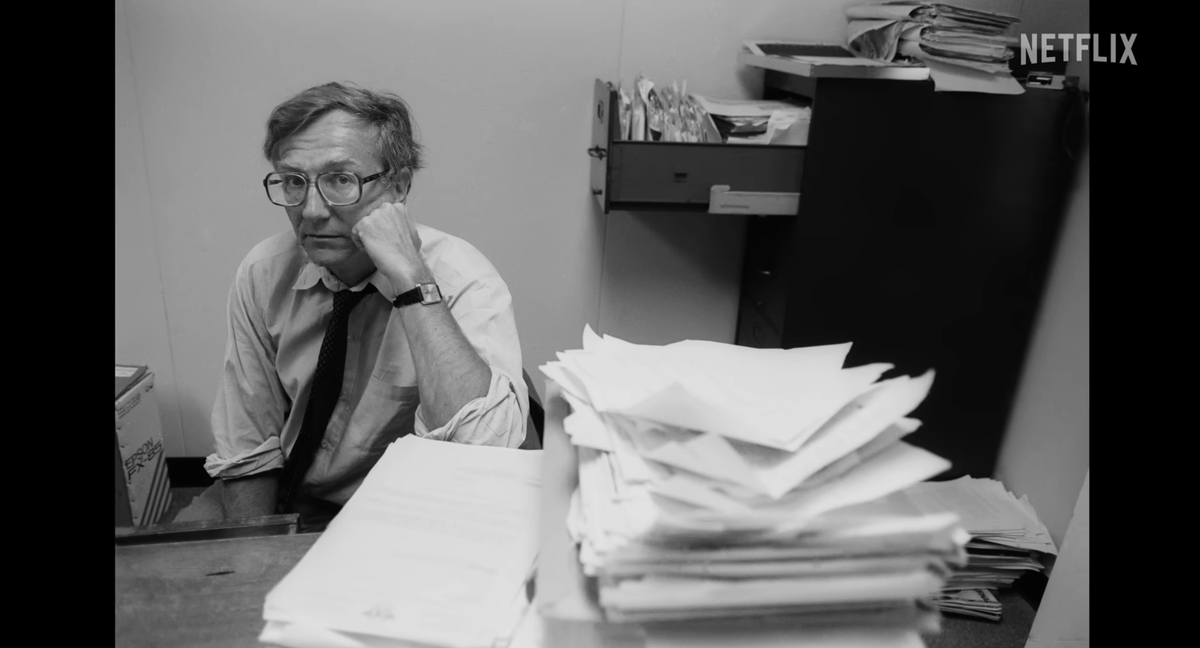

Near the beginning, we see stacks of reporting materials from different eras of Hersh's career. Poitras and Obenhaus were granted extraordinary access that included his notes. However, Hersh doesn't like that they have been looking at the "pads" with names "all over them." He bristles when the filmmakers ask why sources were willing to meet with him.

It makes perfect sense why Hersh would react in this manner. Twenty years ago, he was opposed to any documentary crew getting near him because it could be risky for his sources. Yet these questions honor the anonymous sources who defied a culture of violence and spoke to Hersh. That makes the answers to these questions fundamental to the film.

During another section, Poitras and Obenhaus highlight Hersh’s award-winning reporting on Abu Ghraib. It is made more compelling by Camille Lo Sapio, who provided Hersh with Abu Ghraib photos and appears in the film to recount her decision to become a source.

Hersh has lost a lot of credibility since the 1990s. That is partly due to two episodes involving unreliable sources, which the film addresses.

His 1997 book, “The Dark Side of Camelot,” nearly included forged documents between President John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. In 2013, he wrote a report that sought to undermine a U.S. intelligence assessment that concluded Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had attacked civilians in Ghouta with sarin gas. On camera, Hersh says, “Let’s call that very much wrong.”

These are blemishes in an otherwise legendary career, and one could argue that those in journalism, who view him as a pariah, scorn Hersh because there exists a culture within the news media that makes it harder to forgive his mistakes.

Defying A Half Century Of Self-Censorship

At the age of 85, Hersh has turned to Substack to continue his reporting. He still speaks with sources in an effort to uncover atrocities and unravel cover-ups. For example, in the documentary, we see Hersh speak to an anonymous source who describes how the U.S.-backed Israeli military has used quadcopter to target Palestinian children, which evokes the My Lai massacre.

Poitras and Obenhaus are keenly aware of the through line that may be drawn from Vietnam to Iraq to Gaza. The continuity between these wars not only implicates the U.S. government but also calls into question a U.S. press that tends to provide cover for people in power.

From the start of Hersh’s career, he distinguished himself by refusing to self-censor in order to fit in among colleagues at the Pentagon. He saw little value in Pentagon briefings and learned to go find young officers, talk sports, and then eventually they would share things like it’s “Murder Incorporated there.”

Officials consistently dreaded what Hersh would find out next. One incredible example, as Hersh reveals, involved a source named Bob Kiley, who is no longer alive. Kiley spied on student activists for the CIA. Hersh says James Angleton, chief of the CIA’s counterintelligence department, denied everything and offered him two stories if he would not reveal the massive and illegal spying program known as Operation CHAOS.

Hersh ultimately left the Times because the newspaper constantly avoided controversy. In 1974, the Times withheld his story on the Glomar explorer at the request of CIA Director William Colby. When Hersh took an interest in corruption at Gulf and Western, Rosenthal and others at the newspaper were uncomfortable with how it scrutinized corporate America. So Rosenthal tried to kill the story by making Hersh come up with an extra source for each major claim.

While at the New Yorker, Hersh was deeply bothered by the “puff stories” that ran in the magazine instead of several of his stories on the war in Iraq. The invasion and occupation was “the moral issue of our time,” and Hersh could not believe that the magazine would not do everything to stop it.

In 2004, CBS News’s “60 Minutes” prepared a segment on Abu Ghraib torture. But government officials claimed if photos of detainee abuse aired would “hurt the war.” Hersh was also working on a similar story for the New Yorker. He called up “60 Minutes” and promised to expose the program’s complicity unless the network broadcast the report as planned. The segment aired, blew open a scandal, and won a Peabody Award.

Of course, the timid nature of the prestige media, including the Times, could be understood by the fact that outlets published disinformation and propaganda that helped President George W. Bush’s administration make the case for invading Iraq in 2003.

Times executive editor Bill Keller delayed a report on NSA warrantless wiretapping by Eric Lichtblau and James Risen, who both worked for the newspaper. The bombshell report was eventually published. It described impeachable offenses and won a Pulitzer Prize, though all of this took place after Bush was reelected in 2004.

The following year Washington Post reporter Dana Priest exposed a network of CIA “black site” prisons, where detention and torture in the global “war on terrorism” had occurred. But the Post undermined Priest by refusing to publish “the names of the Eastern European countries involved in the covert program, at the request of senior U.S. officials.”

In 2025, CBS News Editor-In-Chief Bari Weiss censored a story on U.S.-backed torture and abuse of deported immigrants at El Salvador’s “Terrorism Confinement Center. Weiss would undoubtedly help the government cover up the next Abu Ghraib scandal, and she is presently destroying whatever prestige the network’s flagship program may have left.

Journalists, especially those banned from the Pentagon because they would not sign Secretary Pete Hegseth’s loyalty pledge, could respond to the lawlessness of the Trump administration as Hersh would. They could cultivate sources, take advantage of secure submission systems, and publish information that might unravel a military-backed conspiracy to steal Venezuela’s oil.

But if any reporters followed the example set by Hersh, they would have to be critical of more than just Trump and his behavior. They would have to take on a military industrial-complex that they are inclined to champion.

Clearly, the potential for someone like Hersh to obtain credentials is why Hegseth adopted such a censorious media policy. And given the present moment, the main takeaway of “Cover-Up” may be that Hersh is a cautionary figure.

In a country that constantly acts as an unaccountable warfare state, there can be a press. But it most certainly will not be independent.

If you are interested in additional film writing, I have launched a dedicated space over at Substack called The Weekly Matinee.

The articles may not always correspond with what I have traditionally covered at The Dissenter. Some of the posts may even be more amusing and inconsequential. But I welcome anyone who shares my love of movies and how they open our eyes to the world.

Comments ()