Classification Reform Bill Would Give President, Security Agencies Even More Power To Maintain Secrets

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers. Support independent journalism on secrecy, whistleblowers, and press freedom. Subscribe and get a 30-day free trial.

For decades, the United States Congress has allowed the White House and the wider executive branch to assert control over classified information. Members of Congress have been complicit when it comes to a system that classifies more than 50 million documents a year, a benefit for institutions in the national security state that are dependent on secrecy.

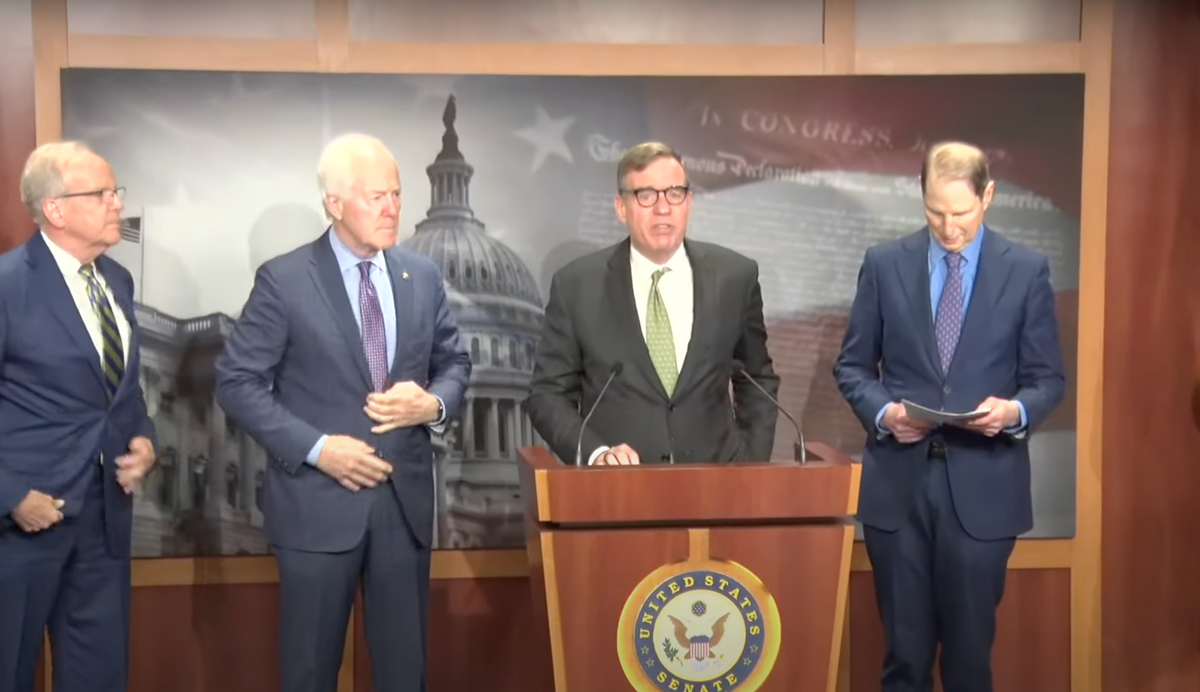

A group of U.S. senators unveiled legislation on May 10, 2023, that they claim will significantly deal with government secrecy and reform the “classification process.” But a closer read of the proposed legislation [PDF] suggests if changes were adopted power would be further entrenched in the hands of the U.S. president and security agencies. Changes would only address the problem cosmetically.

Under the Classification Reform Act of 2023, the head of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) would be designated an “executive agent for classification and declassification.” They would be responsible for “developing technical solutions” for automating declassification, and they would “direct resources” for the development, coordination, and implementation of a federal classification and declassification system for government records.

The bill would establish an executive committee on classification programs and declassification programs that included: the head of ODNI, the under secretary of defense for intelligence, the secretary of energy, the secretary of state, the director of the National Declassification Center, the director of the Information Security Oversight Board (ISOO), the director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and any other individuals that the head of ODNI believes should serve on the committee.

Additionally, it states, “The President shall establish procedures for declassifying information that was previously classified.” Categories for the classification and declassification of information would be determined by the president.

There would even be a process for “reclassification" of information, where the president and security agencies could claw back information that was already released to the public if they determined that “reclassification [was] required to prevent significant and demonstrable damage to the national security.”

Leaving Declassification Up To The President And Director of National Intelligence

Any legislation that further cements the power the president and the director of national intelligence have over classified information will make it harder to deal with rampant secrecy.

Presently, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines has won support from senators by acknowledging that overclassification of information poses a threat to “national security” as well as democracy. But ODNI may not always be led by someone open to taking responsibility for secrecy. It also is unclear what Haines has done to meaningfully break with the status quo.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) sued the U.S. government to force the release of “classified rulings from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court” that would show how the court “interprets key provisions of the laws that authorize mass surveillance.” Congress mandated the disclosure of the decisions when the USA FREEDOM Act was passed in 2015, but the government refused to release the opinions. It was not until August 2022 that ODNI under Haines released the documents.

Even then, the decisions were “heavily redacted.” EFF noted, “Redactions make understanding the importance of some of the newly released opinions difficult.”

The automatic declassification of opinions from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or FISA Court, might be expected under the proposed legislation. Yet one can imagine Haines and others in U.S. national security agencies frustrating efforts to declassify opinions that might open agencies up to scrutiny when it comes to mass surveillance.

Since World War II, Congress has done very little to assert control over the classification system for government records.

The McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950 tinkered with and expanded the Espionage Act, and the Intelligence Identities Protection Act was passed in 1982 to criminalize the unauthorized disclosure of any information that could lead to the identification of covert agents or intelligence sources.

In both those instances, Congress did not attempt to curtail the executive branch’s ability to keep information classified. Senators and representatives were instead concerned with threats to the government's ability to protect state secrets.

That was the case from 2010 to 2013, when WikiLeaks published documents from Chelsea Manning and The Guardian and other media outlets published documents from Edward Snowden. Congress was focused on giving security and military agencies the tools they needed to identify “insider threats” and prevent leaks.

Congress could try to wrest away the control the president has over classified information. The Congressional Research Service noted in February 2023 that the Supreme Court has never settled the question of whether Congress may check the power of the president when it comes to government secrecy.

Independent of the president, the Atomic Energy Act was passed by Congress in 1946 to create a “regime” for protecting “nuclear-related ‘Restricted Data.’” Congress could create a similar but more ambitious system for declassification.

But the classification reform proposed by senators avoids any confrontation with the White House that might spark accusations that Congress is interfering with the power of the president. It also skirts any conflict with U.S. intelligence agency chiefs.

The National Security Council, which advises the president on security and foreign policy, would likely play a big role in determining the categories of information that should be declassified. The council is made up of the vice president, secretary of state, secretary of defense, secretary of energy, secretary of the treasury, attorney general, secretary of homeland security, the ambassador to the United Nations, the administrator for the agency for international development (USAID), the White House chief of staff, the White House national security advisor, and the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff (a military advisor).

Two of those individuals—the secretary of state and the secretary of energy—would sit on the executive committee for classification and declassification of information. The under secretary of defense for intelligence answers to the secretary of defense, who is part of the NSC.

It is unlikely that this executive committee would ever challenge the advisors from the national security state, who directly influence the president’s decisions, because they are part of the web of secretive intelligence and military institutions that maintain databases filled with billions of secrets.

When U.S. Security Agencies Secretly 'Reclassified' Information

Furthermore, if the bill passed, it might contain a “reclassification” process that would present transparency and open government advocates with an easy way for bureaucrats to undermine everything the legislation is intended to do.

Historian Matthew Aid uncovered a secret “reclassification program” in 2006 that he detailed in a report for the National Security Archive at George Washington University.

“Beginning in the fall of 1999, and continuing unabated for the past seven years, at least six government agencies, including the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Defense Department, the military services, and the Department of Justice, have been secretly engaged in a wide-ranging historical document reclassification program at the principal National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) research facility at College Park, Maryland, as well as at the Presidential Libraries run by NARA,” Aid wrote.

“Since the reclassification program began, some 9,500 formerly declassified and publicly-available documents totaling more than 55,500 pages have been withdrawn from the open shelves at College Park and reclassified because, according to the U.S. government agencies, they had been improperly and/or inadvertently released.”

This happened because President Bill Clinton signed an executive order related to classified “national security” information that required U.S. agencies to “declassify all of their historical records that were 25 years old or older by the end of 1999, except for those documents that fell within certain specified exempt categories of records, such as documents relating to intelligence sources and methods, cryptology, or war plans still in effect.”

The CIA and various other U.S. intelligence agencies resisted procedures requiring the mandatory release of information. Together, the most influential parts of the national security state united to convince the National Archives that thousands of records should have never been disclosed to the public.

Such an episode could easily happen again if Congress includes a provision establishing the “reclassification” of records. Like the Clinton executive order, the bill would instruct agencies to automatically declassify information “25 years after the date” it was marked classified.

On top of that, there are sections that allow the president to postpone the release of records. The president would be able to postpone declassification after something has been classified for 25 years—for up to 10 additional years.

That postponement could be applied to a record that is over 50 years old (like many of the files related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy that are still classified).

Senator Ron Wyden, one of the senators who unveiled the legislation, is correct that “far too many records are classified." omething has to be done to deal with the problem. However the solution cannot possibly be empowering the president and the very agencies that have thrived off government secrecy so that they have more control over when they relinquish control over information.

Congress has to carve out a bigger role for itself or else nothing will fundamentally change.

Comments ()