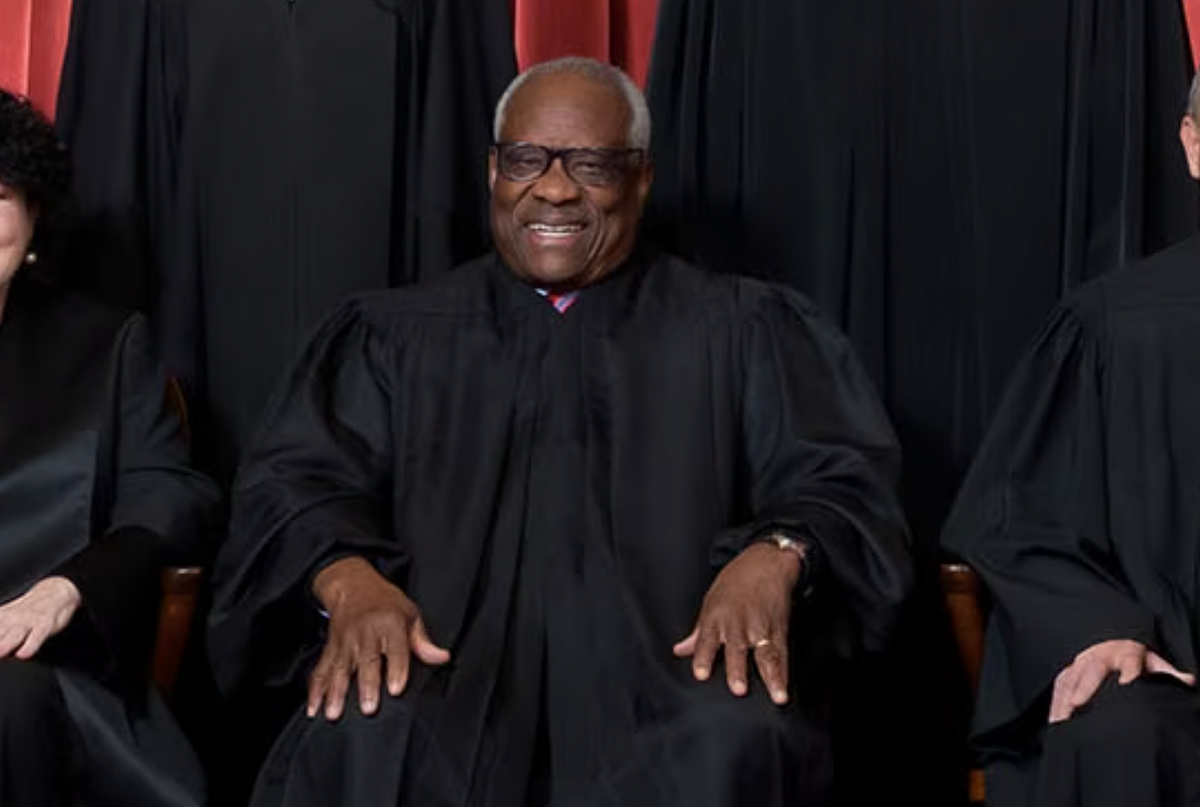

Clarence Thomas Encourages Constitutional Challenge To Whistleblower Law

United States Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas effectively invited corporations accused of fraud to bring a constitutional challenge against the False Claims Act, which could dismantle a law that whistleblowers have depended on for over a century.

On June 16, Thomas issued a dissenting opinion in a case that involved the U.S. government’s authority to dismiss False Claims lawsuits. Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett joined Thomas in his dissent, with Kavanaugh declaring that it was his view that the Supreme Court should consider what Thomas raised in an “appropriate case.”

The False Claims Act, or the FCA, [PDF] is what is known as a qui tam statute. A whistleblower can act as a “relator” and seek civil penalties or rewards from companies that have defrauded the government. They file their complaint under seal and provide a copy to the Justice Department. Prosecutors then elect to “intervene,” or take up the case, or they pass on the case.

If the U.S. Justice Department determines it will not pursue action, the whistleblower is typically free to privately bring a lawsuit against the alleged fraud.

In an 8-1 opinion, United States Ex Rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc., Et Al., the Supreme Court ruled that the government may dismiss a False Claims case over the whistleblower’s objection. The government does not lose the authority to have a case dismissed, even if prosecutors initially choose not intervene.

Thomas, the lone dissenting vote, argued the case should be sent back to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals to consider whether the U.S. Constitution required that the case be dismissed.

“The FCA’s qui tam provisions have long inhabited something of a constitutional twilight zone,” Thomas contended. “There are substantial arguments that the qui tam device is inconsistent with Article II [which establishes the executive branch] and that private relators may not represent the interests of the United States in litigation.”

Thomas maintained that since “executive power” solely “belongs to the President,” the authority to sue companies that defraud the government “can only be exercised by the President and those acting under him.”

Because the whistleblowers are not appointed officers of the U.S., Thomas further suggested that “Congress cannot authorize a private relator to wield executive authority to represent the United States’ interests in civil litigation.”

Thomas’ dissent comes less than a month after he authored the unanimous opinion in a merged case [PDF], which ensured that the FCA was not gutted. Two companies, Safeway and Supervalu, had sought to avoid liability for fraud by redefining what it meant to “knowingly” overcharge Medicare and Medicaid.

Constantine Cannon, a law firm that has represented whistleblowers in FCA cases for 25 years, found it unlikely that an “Article II attack” on the law would succeed. “Congress almost certainly would step in and take whatever steps were necessary to modify the statute accordingly given the strong bi-partisan support this whistleblower program has always had. And for good reason.”

“The Government has recovered tens of billions of dollars under the False Claims Act over the past twenty-five years, the vast majority of which has come from lawsuits initiated by whistleblowers,” the law firm added. “Proof positive, if any were needed, of the critical role whistleblowers play in the Government’s fraud enforcement regime. Just as Congress envisioned when it created the statute more than 150 years ago.”

The United States government has strongly argued [PDF] against any sort of challenge, noting that relators are not acting as “agents” of the United States. The FCA gives them a “personal stake” in the outcome of the lawsuit, which means a whistleblower is not technically wielding executive power.

Thomas has faced scrutiny during the past months for accepting large sums of money from Republican billionaire donor Harlan Crow to pay for “lavish vacations” and “private school tuition for a relative that Thomas considers his son.”

The Lever’s Julia Rock and Andrew Perez reported in May that Thomas has “changed his position” on what is known as the “Chevron deference” doctrine that “stipulates that the executive branch—not the federal courts—has the power to interpret laws passed by Congress in certain circumstances.”

This doctrine has specifically enabled regulation of the environment and cable companies.

“Groups within the conservative legal movement funded by Leonard Leo’s dark money network and affiliated with Thomas’ billionaire benefactor Harlan Crow have organized a concerted effort in recent years to overturn Chevron. That campaign unfolded as they delivered gifts and cash to Thomas and his family in the lead-up to his shift on the doctrine,” Rock and Perez added.

When considering Thomas’ dissent along with the secret money that Thomas has accepted, abruptly calling for a constitutional challenge to the False Claims Act fits into his bought-and-paid-for ideological agenda.

The Congressional Research Service has pointed out that constitutional challenges face an “obvious hurdle” because qui tam statutes were “fairly common at the time of the drafting of the Constitution.” In fact, they were enacted by the very same people who drafted and ratified the Constitution.

However, in 1989, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel took the position [PDF] that the FCA was unconstitutional. It believed that Congress could not give “private parties” the “law enforcement authority” to sue companies for defrauding the government. They also asserted that the law violated the separation of powers doctrine that establishes the executive branch’s power to enforce laws.

“The False Claims Act effectively strips this power away from the Executive and vests it in private individuals, depriving the Executive of sufficient supervision and control over the exercise of these sovereign powers. The Act thus impermissibly infringes on the President’s authority to ensure faithful execution of the laws,” wrote Assistant Attorney General Bill Barr.

Thomas, Kavanaugh, and Barrett undoubtedly share many of Barr’s beliefs in the “unitary executive theory”—a view that essentially embraces concentrated and unchecked presidential power.

The key question is whether these justices wish to upend a settled law that even stalwart conservatives like Chuck Grassley have long championed, particularly because the False Claims Act is an effective means for combating fraud and abuse in federal government programs.

Comments ()