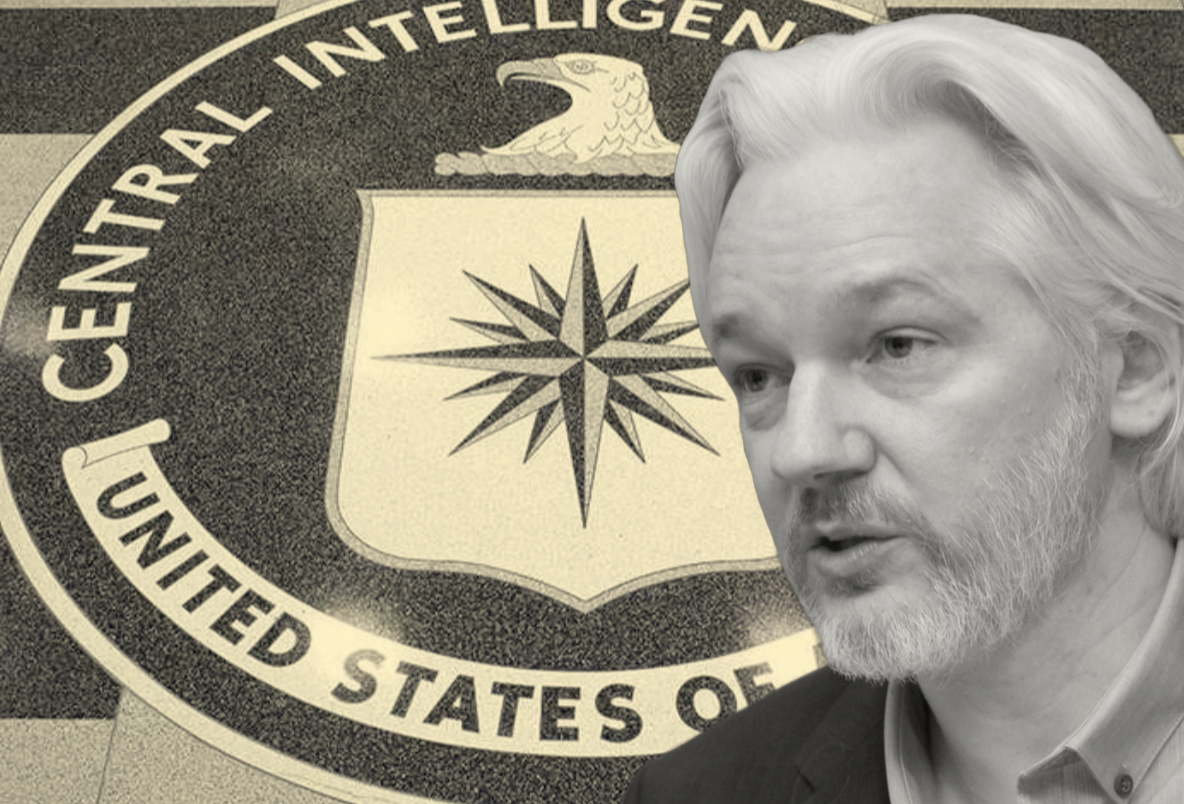

Burying The CIA's Assange Secrets

The CIA won the dismissal of a lawsuit brought by four Americans who claimed they had their privacy rights violated when they visited Julian Assange in Ecuador's London embassy.

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers of The Dissenter. Become a subscriber and support independent journalism on government secrecy, press freedom, and whistleblowing.

A United States judge dismissed a lawsuit pursued by four American attorneys and journalists, who alleged that the CIA and former CIA Director Mike Pompeo spied on them while they were visiting WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in Ecuador’s London embassy.

“The subject matter of this litigation,” Judge John Koeltl determined [PDF], “is subject to the state secrets privilege in its entirety.” Any answer to the allegations against the CIA would “reveal privileged information.”

Few publications followed this case as closely as The Dissenter. It unfolded at the same time that the U.S. government pursued the extradition of Assange, making any outcome potentially significant.

On August 15, 2022, Margaret Ratner Kunstler, a civil rights activist and human rights attorney, and Deborah Hrbek, a media lawyer, filed their complaint. Journalist Charles Glass and former Der Spiegel reporter John Goetz also joined them as plaintiffs.

The lawsuit claimed that the plaintiffs, like all visitors, were required to “surrender” their electronic devices to employees of Undercover Global, a Spanish security company managed by David Morales that was hired by Ecuador to handle embassy security. They were unaware that UC Global had allegedly “copied the information stored on the devices” and shared the information with the CIA.

Pompeo allegedly approved the copying of visitors’ passports, “including pages with stamps and visas.” He ensured that all “computers, laptops, mobile phones, recording devices, and other electronics brought into the embassy,” were “seized, dismantled, imaged, photographed, and digitized.” This included the collection of IMEI and SIM codes from visitors’ phones.

Morales and UC Global were named as defendants in the lawsuit, however, due to the fact that they were not in the U.S., the claims against them were never really litigated.

In December 2023, Koeltl dismissed multiple claims that were filed against the CIA. But remarkably, he found that the four Americans who had visited Assange had grounds to sue the CIA for violating their “reasonable expectation of privacy” under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

“If the government’s search (of their conversations and electronic devices) and seizure (of the contents of their electronic devices) were unlawful, the plaintiffs have suffered a concrete and particularized injury fairly traceable to the challenged program and redressable by a favorable ruling,” Koeltl declared.

Soon after, the court was notified that the CIA would assert the state secrets privilege to block the lawsuit.

Bill Burns, who was the CIA director, submitted a declaration in April 2024 that asserted “serious” and “exceptionally grave” damage to the “national security” of the U.S. would occur if the case proceeded.

Burns added, “[T]he complete factual bases for my privilege assertions cannot be set forth on the public record without confirming or denying whether CIA has information related to this matter and therefore risking the very harm to the U.S. national security that I seek to protect.”

The government “adequately supported its invocation of the state secrets privilege in its public and sealed declarations,” according to the judge.

Koeltl later stated, “The Government persuasively argues that requiring the CIA to acknowledge whether or not it took certain intelligence gathering activities in a foreign embassy could have serious national security repercussions for the United States, even though Assange no longer lives at the Embassy and UC Global no longer provides security there.”

However, as with numerous cases where the state secrets privilege is invoked to deny plaintiffs their day in court, the invocation effectively confirms that “intelligence gathering activities” were undertaken against Assange at the Ecuador embassy. (After all, it’s not like stating the CIA did not engage in such activities would result in “serious national security repercussions.”)

In September 2021, Yahoo News published an investigation “based on conversations with more than 30 former U.S. officials—eight of whom described details of the CIA’s proposals to abduct Assange.”

Pompeo allegedly “championed” proposals to abduct Assange after WikiLeaks published the Vault 7 materials in 2017. Pompeo favored a rendition operation that would involve breaking into the Ecuador embassy to drag Assange out and bring him to the U.S. “via a third country.”

“A less extreme version of the proposal involved U.S. operatives snatching Assange from the embassy and turning him over to British authorities,” Yahoo News also reported.

Koeltl referred to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in a state secrets privilege case on March 3, 2022. It involved the CIA and stemmed from an attempt by Abu Zubaydah, a high-profile Guantanamo Bay prisoner, to subpoena two CIA contractors named James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen. Both were architects of the agency’s torture program, who interrogated Zubaydah at a black site in Poland.

The CIA invoked the state secrets privilege to block Zubaydah from seeking testimony that could be used in a Polish criminal investigation. The Supreme Court overturned an appeals court decision that asserted the privilege did not cover all of the information requested.

As The Dissenter has emphasized, the 1953 case known as U.S. v. Reynolds that established the state secrets privilege is rooted in fraud. After a military plane crash, the government refused to tell the victims’ families how their loved ones had died because officials claimed that would reveal “secrets.” But decades later, families filed a lawsuit [PDF] after reading declassified U.S. Air Force documents.

“The government concealed its fraud for decades, holding the accident reports and witness statements as ‘classified materials’ until the 1990s, even though they contained no secrets and had no conceivable further utility,” the families alleged. “Indeed, that was the Air Force’s purpose in classifying them—to bury them so deep and so long that no one would find them.”

Burying secrets so deep and for so long that the public does not find them is typically the CIA’s objective when they invoke the state secrets privilege. They have buried a 6,300-page Senate intelligence report on CIA rendition, detention, and torture during the global war on terrorism. They are now burying their Assange secrets.

The decision all but ensures that the CIA will be able to conceal what they allegedly did to Assange, WikiLeaks, and his supporters for several decades. The agency, with support from the U.S. Justice Department, has already frustrated a Spanish court trying to prosecute Morales and other UC Global employees for alleged criminal acts.

It was always unlikely that Assange’s defense would uncover details about the CIA’s alleged actions and share those revelations during an Espionage Act trial. The restrictions the government and courts impose on defendants come with procedures to shield the CIA from scrutiny.

When the prosecution against Assange ended in a plea deal in June 2024, that benefited the CIA even if it was not the outcome that current and former high-ranking officials had desired. The CIA would never have to worry about the agency’s actions being discussed by the press and on social media during a high-profile trial.

Of course, there is also the matter of the CIA allegedly violating the privacy rights of Assange visitors while the U.S government targeted a journalist living under political asylum in a foreign embassy. The U.S. news media never showed much interest in the CIA’s actions, however, let's not forget there was widespread global opposition to the Assange prosecution that helped end the case. The agency is right to be concerned that if more was known it might erupt into an international scandal.

Comments ()