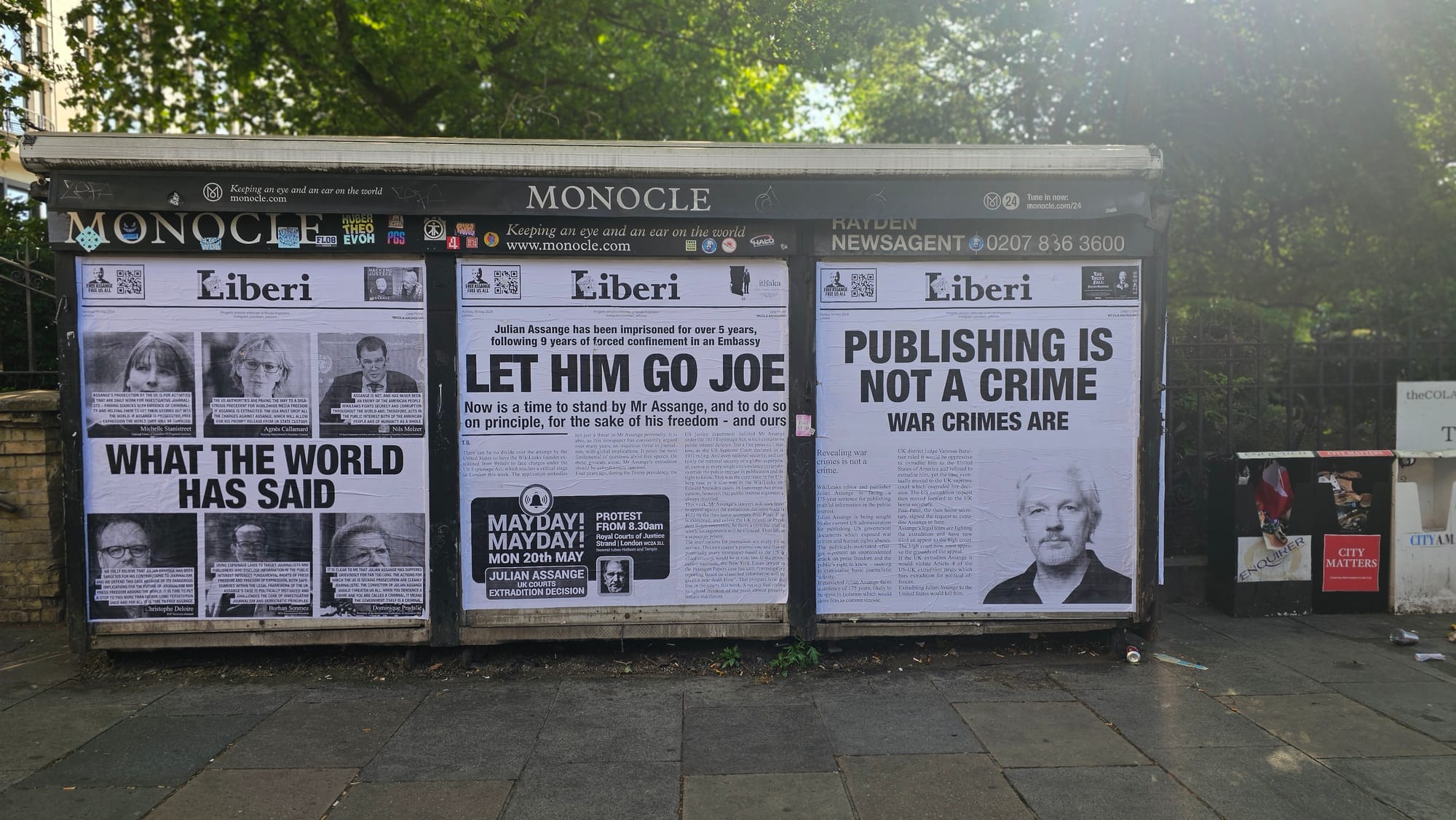

US Effort To Extradite Assange Hits Roadblock As British High Court Grants Appeal

It was the first positive court decision for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in quite a while.

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers of The Dissenter. Become a subscriber with this special offer and support independent journalism on press freedom.

The High Court of Justice in London granted WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange the right to appeal his extradition after a two-hour hearing. It was the first positive decision in the case since District Judge Vanessa Baraitser barred his extradition on mental health grounds in January 2021.

Mr. Justice Johnson and Dame Victoria Sharp explained that having carefully considered the written and oral submissions presented by both parties they “decided to give” the right to appeal on two grounds related to all charges brought by the United States Department of Justice.

This means that Assange will be allowed to present more detailed arguments as to why his extradition to face 18 criminal charges—17 of which are Espionage Act charges—must be blocked. Or else Assange will have his rights to freedom of expression violated since the First Amendment does not cover him as an Australian citizen.

Assange, an award-winning journalist, faces a maximum of 175 years in prison for his role in receiving and publishing classified materials relating to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Guantanamo Bay detainee files, and diplomatic cables. No other individual or press organization which participated in the publications of these very documents, including the New York Times, Washington Post and The Guardian, have faced criminal charges.

Throughout Assange’s extradition case, the U.S. government has argued that he would not be permitted to argue that his publications were protected under the First Amendment — because he is a non-U.S. citizen whose activities occurred outside the U.S.

“[C]oncerning any First Amendment challenge, the United States could argue that foreign nationals are not entitled to protection under the First Amendment, at least as it concerns national defence information,” U.S. prosecutor Gordon Kromberg stated in a sworn declaration.

This statement, which the U.S. government submitted as an argument in its favor during Assange’s substantive extradition hearings, appears to have now backfired.

The First Amendment Assurance Does Little To Remove Concerns

In March, the High Court rejected most of Assange’s grounds of appeal: that extradition is prohibited for political offenses; that he would not receive a fair trial in the Eastern District of Virginia; that privileged lawyer-client conversations were spied upon by the CIA; and that the court should accept his request to present fresh evidence that the CIA plotted to kidnap and assassinate him, thereby poisoning any possibility of a fair trial.

However, the High Court judges appeared concerned that Assange might face the death penalty and that he might face discrimination based on his status as a foreign national.

“The concerns that arise under these grounds may be capable of being addressed by assurances (that the applicant is permitted to rely on the First Amendment, that the applicant is not prejudiced at trial (including sentence) by reason of his nationality, that he is afforded the same First Amendment protections as a United States citizen, and that the death penalty is not imposed),” the High Court ruled in March.

While Assange’s legal team accepted the death penalty assurance, they wholly objected to the assurance related to his right to assert First Amendment protections.

The U.S. offered a toothless and unenforceable assurance, stating merely that Assange could “seek to raise” First Amendment arguments “at trial and at sentencing”:

“ASSANGE will not be prejudiced by reason of his nationality with respect to which defenses he may seek to raise at trial and at sentencing. Specifically, if extradited, ASSANGE will have the ability to raise and seek to rely upon at trial (which includes any sentencing hearing) the rights and protections given under the First Amendment of the constitution of the United States. A decision as to the applicability of the First Amendment is exclusively within the purview of the US Courts”

This assurance “does not promise that [Assange] can rely on the First Amendment. Merely that he can raise and seek to rely on it,” Assange’s barrister Edward Fitzgerald KC told the High Court.

“It does not commit the prosecution not to take the point, which gave rise to this court’s concerns, i.e. the point that as a foreign citizen he is not entitled to rely on the First Amendment, at least in relation to a national security matter,” and “it cannot and does not bind U.S. courts.”

As asserted in the written submissions from Assange’s lawyers, “The protection enshrined in [the UK Extradition Act 2003] replicates a well-established protection from discrimination in refugee and extradition law. As such, it must be given a broad and purposive construction that accords a full measure of protection."

“To discriminate on grounds that a person is a foreigner, whether on the basis that they are a foreign national or a foreign citizen, is plainly within the scope of the prohibition. ‘Prejudice at trial’ must include exclusion on grounds of citizenship from fundamental substantive rights that can be asserted at the trial. On the U.S. argument, trial procedures could discriminate on grounds of citizenship.”

High Court Bothered By Risk To Assange's Freedom of Expression

The use of the Espionage Act to prosecute a publisher for publishing truthful and newsworthy information is unprecedented. It is not a matter which U.S. courts have addressed.

Still, the court heard that there is case law to support Kromberg’s proposition that non-U.S. persons are barred from claiming First Amendment protection for statements that they made outside the U.S., even while they are being prosecuted by the U.S. government.

In essence, Assange faces a criminal trial under U.S. law without the same rights and privileges that a U.S. citizen would receive in the same circumstances.

The right to receive and impart information, which includes the right to journalistic activity, is guaranteed under Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (although like most human rights it is not absolute).

The High Court, as well as previous judges in this case, have largely dismissed the Article 10 arguments on the basis that Assange would be entitled to assert any First Amendment protections at trial in the U.S. This is the position District Judge Vanessa Baraitser took in her January 2021 decision. However, the High Court today was clearly concerned that such protections would be denied Assange simply because he is not a U.S. citizen.

The U.S. government emphasized two main arguments, which did not seem to impress the judges.

The first argument was that the High Court was “wrong," in its March judgment, “to equate prejudice on grounds of foreign nationality with discrimination on grounds of foreign citizenship.” In other words, the U.S. asserted that the High Court should never have raised the potential risk of discrimination.

The second argument made by the U.S. was that the U.K. Extradition Act bars discrimination based on “nationality” and not “citizenship.” James Lewis KC argued that the assurances provided by the U.S. would satisfy any concerns about discrimination in relation to his “nationality,” removing any concerns about discrimination due to his status as an Australian citizen.

“Even if nationality and citizenship are meant to be synonymous terms under the 2003 Act—and we submit that they are not—the applicability of [Assange’s] First Amendment argument” [depends upon] the components of (1) conduct on foreign (outside the United States of America) soil; (2) non-U.S. citizenship; and (3) national defence information,” the U.S. wrote in its submissions.

This argument was rebutted by the defense as “novel,” “unsupported by any expert evidence,” and having been “made for the first time at this stage.”

Mark Summers KC, Assange’s other barrister, insisted, “That there is a legitimate basis to treat Mr Assange differently at his trial on the basis of his nationality and citizenship is entirely wrong.” “You can be a national without being a citizen” he noted, “[but] you cannot be a citizen without nationality.”

As a result, any discrimination based on citizenship “necessarily” results in discrimination based on nationality, Summers said.

“The notion that this is permissible discrimination based on different attributes of nationality against non-nationals in wrongheaded…. But most importantly… those cases [cited by the U.S. government] have nothing to do with this trial.”

“The core point about these cases [cited by the U.S.],” Summers added, “is that they absolutely do not support that [the law] permits discrimination based on citizenship at trial.”

Summers contended, “In addition to being a non-U.S. citizen, Mr Assange is a non-U.S. national as well. Whatever the distinction may be, and we don’t accept that there is any…it has no bearing whatsoever.”

While the Assange legal team opposes this legal argument, the U.S. government maintains that only three of the Espionage Act charges (counts 15-17) criminalize the general publication of information. They attempted to convince the High Court to limit the appeal on First Amendment issues to these three counts, but the judges were unpersuaded.

This was ultimately rejected by the High Court today when it made clear that Assange will have the right to argue that he faces unlawful discrimination on the basis of his nationality (in relation to his right to assert Article 10 and First Amendment protections). The decision applies to all 18 charges.

U.S. Government 'Putting Lipstick On A Pig'

“We spent a long time hearing the United States putting lipstick on a pig, but the judges did not buy it,” Stella Assange said after the court adjourned.

Reporters Without Borders’ international campaigns director Rebecca Vincent called today’s result “an important milestone,” which opens up “a vital new path to prevent extradition.”

Julian Assange was informed about the positive news by his lawyers and spoke to his wife briefly about it before being told that he had to leave to go exercise in the yard of Belmarsh, the U.K.’s harshest prison where he has been held since his arrest in April 2019.

“While I was speaking to Julian a guard knocked on the door and I could hear the guard saying ‘congratulations today’ and ‘it’s time to go exercise’,” Stella shared. “It meant that today he was able to go out into the yard and enjoy the sunshine out today. He was obviously relieved. He did not sleep last night.” “He is obviously under enormous pressure. It’s hard for all of us to imagine what it is like for Julian, who has been in Belmarsh for over five years. And who has had to endure this grueling process from inside his cell and isolated from everyone,” Stella concluded

The court was told in the morning that Assange declined to attend proceedings “due to health reasons.”

Both the Assange legal team and lawyers representing the U.S. government have until May 24 to submit a draft order, which will determine when the appeal hearing granted by the High Court will be held.

Dissenter editor Kevin Gosztola's report on the British High Court's decision to grant an appeal on the question of the First Amendment

Comments ()