Assange Is No 'Ordinary Journalist': US Opposes Request For Appeal

The U.S. government defended their prosecution of Assange saying he is no "ordinary journalist" and WikiLeaks is not a legitimate publisher.

During a hearing at the British High Court of Justice, the United States government responded to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s request for an appeal by explicitly and forcefully arguing that Assange was no “ordinary journalist” who deserved human rights protections.

Lawyers supporting extradition repeated the questionable assertion that the extradition treaty between the U.S. and the United Kingdom does not protect anyone from being extradited to America for “political offenses,” like “espionage.”

For his part, Edward Fitzgerald KC, an attorney for Assange, reiterated arguments from yesterday, including the fact that a bar against extradition for political offenses is entrenched in U.K. law and practice. Fitzgerald said it makes no sense for the U.S. to be able to seek extradition under the U.S.-U.K. treaty while also claiming that the provision against extradition for political offenses is not part of the law.

The High Court judges did not issue a decision. They reserved their judgment for a later date. It could be days or weeks before they grant or deny Assange’s request for an appeal hearing.

Central to the U.S. government’s opposition is the allegation that Assange and WikiLeaks “solicited” others to commit criminal acts by “stealing” classified government documents.

“[T]here is no immunity for journalists to break the law,” Clair Dobbin KC said on behalf of the prosecution. It would be “frivolous to assert, and no one does” that the “First Amendment” confers a right to violate valid criminal laws, she added.

Framing Assange’s encouragement to leak materials in the public interest as “soliciting” sources to “steal” documents is a stark reminder of the unprecedented threat that this case poses to journalism in the U.K. and the U.S. Journalists all over the world regularly ask sources to share information with them.

“[WikiLeaks] disclosed to the world the unredacted names of the sources who provided information to the United States, many of them lived in war zones or in repressive regimes,” Dobbin stated. And, “It is alleged the appellant did publish those classified documents that were stolen from the United States.”

Dobbin continued, “What the appellant is accused of is really at the upper end the spectrum of gravity,” she added, insisting that it attracted “no public interest whatsoever,” and that Assange “created a grave and imminent risk” that people would “face harm or injury.”

But in fact, Assange’s defense provided many examples of how the information was in the public interest. One example is the case before the European Court of Human Rights, where Khaled El-Masri used diplomatic cables to secure a “damning judgment” against Macedonia for their role in the kidnapping and torture he suffered at the hands of the CIA.

The Target is ‘Legitimate Journalism’

It was clear that Dobbin and prosecutors wanted the High Court to view Assange’s alleged conduct as acts that were well beyond the scope of “legitimate journalism.”

In response, Assange’s other barrister, Mark Summers KC, told the court that the activity that Assange engaged in was clearly “ordinary” journalistic activity. Assange exposed actual “war crimes,” which must be weighed against unsubstantiated claims of “harm.”

This is a point that nearly every expert, who gave evidence during the substantive extradition hearing in 2020, also made clear.

“Good reporters don’t sit around waiting for someone to leak information. They actively solicit it; they push, prod, cajole, counsel, entice, induce, inveigle, wheedle, sweet-talk, badger, and nag sources for information—the more secret, significant, and sensitive, the better,” journalism professor and historian Mark Feldstein wrote in his witness statement to Westminster Magistrates’ Court in 2020.

Summers later said that the defense has never argued that journalists are immune from prosecution in the U.S. or U.K. He was unsure why the prosecution would suggest that the defense believed journalists are above the law.

Recycling Discredited and Debunked Arguments

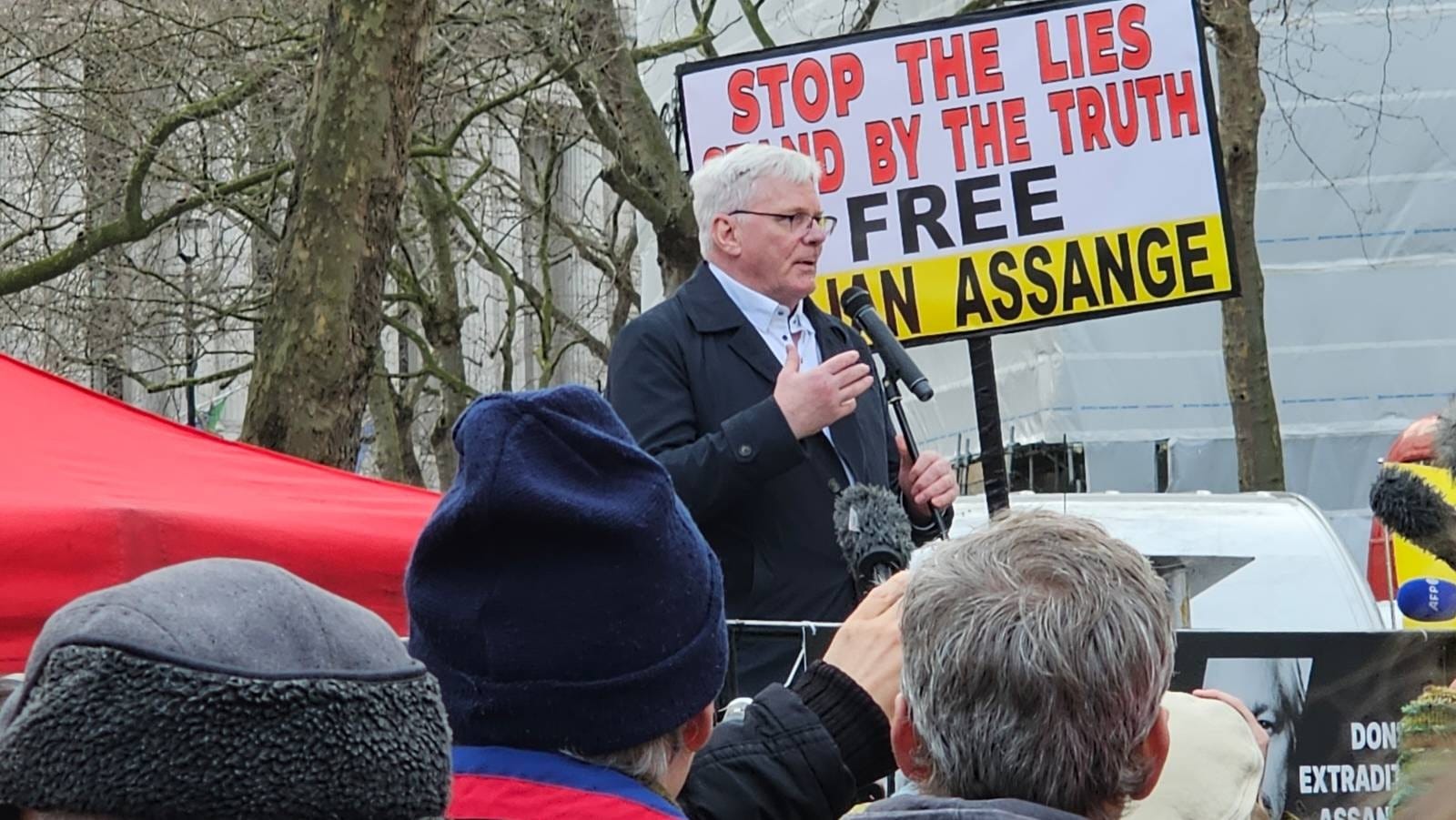

WikiLeaks editor-in-chief Kristinn Hrafnsson told Assange supporters outside the courthouse that prosecutors had put forward "nothing new."

"It was as if we were out to lunch on a leftover smorgasbord from last month. We've heard it all before, and it's all been refuted. Not just in the courtrooms, but with new evidence that was totally disregarded," Hrafnsson added.

Dobbin repeated the debunked allegation that Assange had instructed others to engage in computer intrusion. As the Icelandic paper Stundin reported, these claims were made by a former WikiLeaks volunteer who later admitted to fabricating the claims in exchange for a promise of immunity by the FBI in relation to charges of fraud that he faced in Iceland.

Prosecutors said that by publishing unredacted cables—which contained the names of sources in countries, such as Iran, Syria and China—Assange “created a grave and imminent risk” that people would “face harm or injury.” And Dobbin further asserted that the publications “damaged the capability of the United States forces” and “endangered” U.S. national interests.

But a secret Pentagon report from 2011 concluded that the Afghanistan war log publications would not result in “significant impact” on U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and asserted with “high confidence” that “disclosure of the Iraq data set [would] have no direct personal impact on current and former U.S. leadership in Iraq.”

WikiLeaks Did Not Publish Unredacted Cables First

Mr Justice Johnson asked Dobbin about the fact that by the time Assange had published the unredacted cables they had “already been published by others who are not being prosecuted.”

Amazingly, Dobbin insisted that Assange was “responsible for the publications of the unredacted documents, whether published by others or WikiLeaks.”

Dobbin added that “these are matters that he is free to litigate in the United States,” a point also made by District Judge Vanessa Baraitser in her 2021 ruling. However, as the lower court judge was made acutely aware—because the charges under the Espionage Act are strict liability offenses—it doesn’t matter who published the documents first, what his motivations were for publishing the documents, or whether any harm occurred as a result.

“If, in this country, a journalist had information of very serious wrongdoing by an intelligence agency and incited an employee of that agency to provide information… [which] was then published in a very careful way…do you say a prosecution would be compatible with Article 10 [right to freedom of expression]?” Justice Johnson later asked.

Dobbin wasn’t certain that there was a “straightforward answer.”

“The submission you just made is that you only look at the statutory offense,” Johnson noted, adding that Dobbin said that there is “no scope for a balancing exercise” and that “Article 10 has no role to play.”

Dobbin suggested that was the logical interpretation from relevant case law. She then conceded that there would be a “proportionality assessment” in the case of a prosecution of a publisher under Section 5 of the U.K. Official Secrets Act.

A prosecution “would only get off the ground” if one “knowingly published” information, which they “knew to be damaging," Dobbin said.

Under the U.S. Espionage Act, there is no such assessment because no damage needs to be established in order to secure a conviction. All that must be established is that they had “reason to believe that the information is to be used to the injury of the U.S.”, and that typically turns on the mere fact that the information was classified.

Summers KC reminded the High Court that there is no actual proof of any harm occurring to sources identified in documents published by WikiLeaks in 2010.

On the other hand, there is substantial evidence of actual war crimes, including “drone attacks” against civilians and “torture" at "black site" prisons, which was not only exposed but in many instances ended as a result of the disclosures.

The European Court of Human Rights would say that there must be an Article 10 balancing exercise in cases such as these, Summers told the judges. They would look at any alleged harm on the one hand (for which there is no actual proof) and the public interest in disclosure on the other. In this case, the public interest is conclusive proof of state-perpetrated war crimes.

If Assange’s case were to be considered by the European Court of Human Rights, it would note that there are “only three counts out of 18” which relate to publications that contained named U.S. sources.

According to Summers, the European court would also “remember the extraordinary efforts” taken by Assange and WikiLeaks to redact the names of individuals, and the fact that a year later staff of The Guardian published the key to the encrypted internet file containing the unredacted cables in their book.

Summers stated that the European court would also consider how Assange “scrambl[ed] around desperately to try and prevent the revelation of any names becoming public”, including by phoning the U,S government “to put in place urgent and immediate efforts to protect those names”—something which the U.S. government chose not to do.

Finally, Summers noted that the European court would consider how the unredacted cables were first published by others; for example, Cryptome.

Yet the lower court failed to carry out this balancing test when assessing whether the charges violated Assange’s Article 10 rights (freedom of expression). This was an error in law, Summers asserted.

Publishing the names of government sources is actually not a crime under U.S. law, and Summers insisted that individuals are legally protected from prosecution for publishing information that exposes state crimes.

Assange Defense's ‘Implication’ That This Is A Politically Motivated Prosecution

The lawyers representing the U.S. urged the judges to consider the “implication” behind the defense’s arguments that the prosecution was launched in “bad faith”; specifically, that lead U.S. prosecutor Gordon Kromberg and other U.S. officials have lied about the case.

“The starting position must always be…the fundamental assumption of good faith on the part of countries, which the United Kingdom has long established relationships,” she told the judges.

“We don’t suggest that Kromberg is lying,” Summers replied. “You can’t focus on the sheep and ignore the shepherd,” he said, adding, “What has happened here is state retaliation ordered from the very top.”

Kromberg, along with former CIA director Mike Pompeo, asserted that the U.S. government could argue that Assange has no First Amendment rights because he is an Australian citizen.

Assange’s lawyers therefore claimed that he is at risk of discriminatory treatment as a non-U.S. citizen if he is denied any protections granted under the First Amendment. Dobbin nonetheless told the court that there was insufficient evidence to substantiate that Assange “would be prejudiced at his trial” as a result of his nationality.

Justice Johnson pointed out that “the test isn’t that he would be prejudiced. It is that he might be prejudiced on the grounds of his nationality.”

“It is difficult, isn’t it,” Johnson said, “to reconcile” the position that Assange may be denied First Amendment protections with the section of the U.K. Extradition Act that prohibits extradition if “he might be prejudiced at his trial or punished, detained, or restricted in his personal liberty” because of his nationality.

“Do we have any evidence that a foreign national is entitled to the same rights as a U.S. citizen?” Johnson asked. Dobbin was uncertain.

Significantly, the issue of the death penalty was raised. Extradition from the U.K. is barred if there is a risk that the requested person will be sentenced to death.

“If the appellant is extradited,” Johnson asked, “is there anything to prevent amending the charges of aiding and abetting [a leak]?”

Ben Watson KC, who was instructed to represent the U.K. Home Secretary, replied, “The short answer is no.”

“Do you accept that those charges could carry the death penalty?” Johnson asked.

“In principle, yes,” Watson answered.

Johnson asked, "Is there anything that can be done to prevent a death penalty [from] being imposed?”

“It would be very difficult to offer assurances to prevent the death penalty from being imposed,” Watson admitted.

Yet the UK Home Secretary's office was unwilling to say that Home Secretary Priti Pratel had made the wrong decision when she authorized Assange’s extradition to the United States.

Comments ()