Reporter's Shield Law Introduced In US Congress: A Breakdown

The PRESS Act would ensure “reporters cannot be compelled by the government to disclose their confidential sources or research files.”

A federal shield law was introduced in both houses of the United States Congress in response to the secret seizure of journalists’ records by the Justice Department.

During President Donald Trump’s administration, reporters at CNN, the New York Times, and the Washington Post had their data targeted as part of retaliatory leak investigations aimed at identifying the sources for stories that brought negative attention to the White House.

President Barack Obama’s administration was also embroiled in a scandal after it became known that the Justice Department seized records in April and May of 2012 from “more than 20 separate telephone lines” used by the Associated Press and their journalists.

Attorney General Eric Holder responded to the backlash among the press by adopting media guidelines that were aimed at curbing the abuse of secret subpoenas in criminal investigations.

There are a patchwork of state laws that protect journalists, but none provide protection from the federal government. In fact, Congress has failed to pass reporter's shield laws multiple times during the past 15 years.

Democratic Senator Ron Wyden introduced the Protect Reporters from Excessive State Suppression (PRESS) Act on June 28, and a version of that legislation was introduced in the House of Representatives on July 6 by Democratic Representatives Jamie Raskin, Ted Lieu, and John Yarmuth.

It is backed by the News Media Alliance, the Radio Television Digital News Association, the Society of Professional Journalists, the National Association of Broadcasters, and the News Leaders Association.

The PRESS Act, according to a summary from Wyden’s office, would ensure “reporters cannot be compelled by the government to disclose their confidential sources or research files.”

Under the legislation, a court in the judicial district in which a subpoena, court order, or search warrant must determine whether the records are necessary to prevent or identify “any perpetrator of an act of terrorism.” They must conclude the records are “necessary to prevent a threat of imminent violence, significant bodily harm, or death.”

If an agency cannot meet that threshold, they would be blocked from seizing a reporter's records.

Additionally, the proposed shield law would protect “data held by third parties like phone and internet companies from being secretly seized by the government without the opportunity to challenge those demands in court.”

Both journalists and internet service providers covered under the law would have an opportunity to come before a federal judge to challenge the government’s efforts to obtain records.

Stronger Than Prior Proposed Federal Shield Laws

The proposed shield law is stronger than a prior version that was called the Free Flow of Information Act and proposed by Senator Chuck Schumer in 2013 as a response to the attack on the Associated Press’ confidential sources.

The 2013 version said a federal agency could access the records if the federal government “exhausted all reasonable alternative sources” and if the agency had “reasonable grounds to believe that a crime” occurred.

In the recently introduced legislation, the standard is tightened. The records must be necessary to identify the perpetrator of an act of terrorism or to prevent a “threat of imminent violence, significant bodily harm, or death.” It is not enough to merely show a crime was committed.

The shield law put forward in 2013 also allowed an agency to contend there were “reasonable grounds to believe that the protected information” is “essential to the investigation or prosecution or to the defense against the prosecution.” That loophole is not in the PRESS Act.

An entire section in the 2013 version covered matters outside of criminal investigations or prosecutions. It allowed agencies to seize records if they were “essential to the resolution of the matter” or if compelling their disclosure outweighed the “public interest in gathering and disseminating the information or news at issue.”

The PRESS Act is missing this loophole that contemplated "matters" outside of criminal investigations or prosecutions, where agencies could subpoena records.

Raskin backed a 2007 version of the Free Flow of Information Act that then-Representative Mike Pence supported. It passed in the House of Representatives with a 398-21 vote.

The 2007 shield law proposed loopholes permitting agencies to still seize the records if they needed to identify a person who disclosed a “trade secret,” “individually identifiable health information,” or “nonpublic personal information.”

It also contained a provision that specifically allowed the seizure of records as part of a leak investigation, which is exactly the circumstance in which the Trump administration seized records from CNN, the New York Times, and the Washington Post and sparked a backlash.

Fortunately, the 2021 shield law introduced in both houses contains no section exempting leak investigations.

One weakness is a section that permits a delay of the notice and opportunity for a journalist to be heard before a judge for 45 days if allowing that journalist to contest the subpoena would pose a “clear and substantial threat to the integrity of a criminal investigation.”

Most of these cases will be heard by judges in the Eastern District of Virginia in Alexandria, who are extraordinarily deferential to the so-called national security interests and preferences of prosecutors. Judges could undercut the purpose of the law by granting delays.

In fact, it seems a bit confusing. If the agency is granted a delay for notifying a media organization of a subpoena, will they delay the seizure of records too?

Excluding Certain People From Protection

The PRESS Act will likely have to move through the Senate Judiciary Committee in order to make it to a full Senate vote.

Senators John Cornyn and Tom Cotton—both on the committee—will definitely oppose the proposed shield law while also working to mold it in ways favorable to national security agencies.

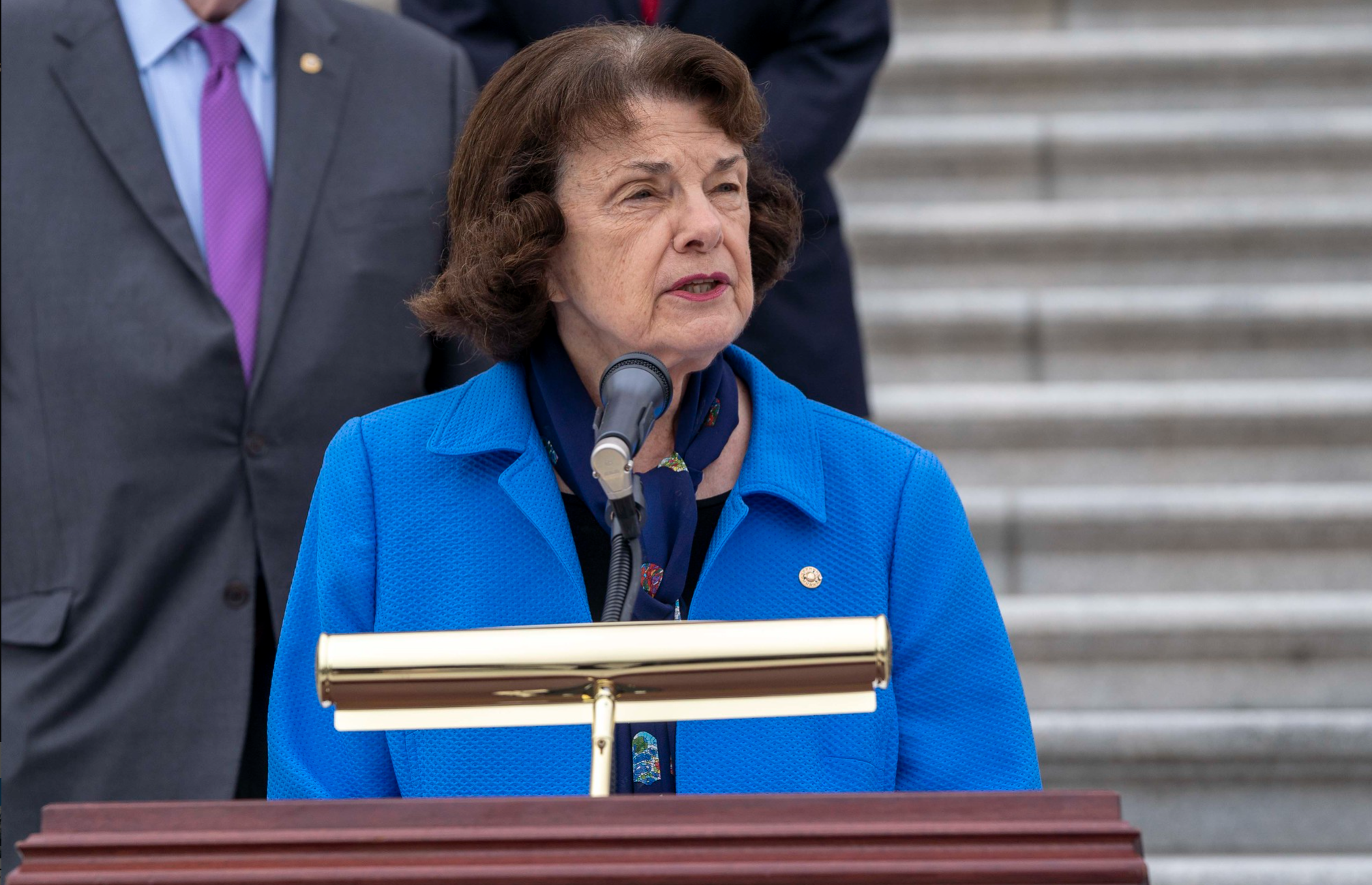

Senator Dianne Feinstein is also still on the committee, and she pushed senators in 2013 to exclude certain people from the definition of “covered journalist.”

Rather than protect the act of journalism, Feinstein’s amendment defined a journalist as:

…an employee, independent contractor, or agent of an entity or service that disseminates news or information by means of newspaper; nonfiction book; wire service; news agency; news website, mobile application or other news or information service (whether distributed digitally or other wise); news program; magazine or other periodical, whether in print, electronic, or other format; or through television or radio broadcast, multichannel video programming distributor (as such term is defined in section 602(13) of the Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C. 522(13)), or motion picture for public showing...

Feinstein made it clear she could not support a shield law "if anybody who sits down and goes out on a blog is suddenly a journalist." As she argued, "Otherwise, it's open sesame. Anybody can say anything with no background, no integrity. If [Edward] Snowden were to sit down and write this stuff, he'd have a privilege and I'm not gonna go there."

She even advocated for an anti-WikiLeaks section that stated anyone “whose principal function, as demonstrated by the totality of such person or entity’s work, is to publish primary source documents that have been disclosed to such person or entity without authorization" should not be covered.

Nothing proposed by Feinstein back in 2013 is in the PRESS Act, though it seems likely that at least one senator will promote panic when it is marked up in committee and baselessly claim it would protect WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange or a person suspected of a leak.

The proposed law clearly outlines how it does not prohibit the federal government from pursuing an investigation against a reporter or media organization that is suspected of a crime, that witnessed a crime “unrelated to engaging in journalism,” or that is suspected of being an “agent of a foreign power.”

A reasonable basis for prosecuting Assange and targeting WikiLeaks does not and has never existed. The conduct of the Justice Department under Obama, Trump, and President Joe Biden represents an assault on freedom of the press.

That stated, if the PRESS Act was enacted prior to the investigation and prosecution against WikiLeaks, it would not be a barrier.

Prosecutors and government officials remain convinced Assange and WikiLeaks were involved in crimes unrelated to journalism. (They have even suspected them of being “agents of a foreign power," though Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation was unable to find concrete evidence to support this suspicion.)

“President Biden and Attorney General [Merrick] Garland have pledged to end these surveillance abuses, but the new policies can be reversed by future administrations,” Wyden asserted. “There need to be clear rules protecting reporters from government surveillance written into black-letter law.”

Raskin contended, “The Trump Administration was not the first administration that attempted to obtain journalists’ information from third party sources, nor will it be the last if we do not correct the problem at its source."

“Without a federal shield law, we render reporters and journalists vulnerable to threats of prosecution or jail time simply for doing their jobs."

Comments ()